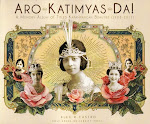

QUEEN OF ALL BOTTLES. A rare Reyna softdrink bottle with old ads from the 1930s Pampanga daily, Ing Cabbling.

QUEEN OF ALL BOTTLES. A rare Reyna softdrink bottle with old ads from the 1930s Pampanga daily, Ing Cabbling.The Nepomucenos of Angeles, led by the patriarch Juan de Dios Nepomuceno and wife Teresa Gomez, have always been instrumental in charting the progress and growth of Angeles. Their many enterprises—ice and electric plants, a high school that grew into a university, numerous prime residential and commercial developments-- helped define the future of Angeles by generating long-term livelihood opportunities, drawing students by the thousands from all over Central Luzon and reshaping the town’s layout.

One other homegrown business that they ventured into that is largely unknown is softdrink manufacturing. In 1928, the Nepomucenos opened a softdrink outlet along Sto. Rosario St., with 2 brands: the more affordable 2-centavo “Aurora”, (named after one of the couple’s daughter ) and “Reyna”, sold at 5 centavos. The drinks came in Orange, Strawberry, Cream Soda, Lemonade and the all-time favorite, Sarsaparilla. Root beer then was thought of as a health-giving drink, which explains sarsaparilla’s popularity. Family members and household helps capped and paper-labelled the bottle manually. The cases of softdrinks were delivered by trucks to outlets all over Pampanga and in Bataan.

Somehow, “Reyna Softdrinks” wide popular appeal worried the San Miguel Brewery, makers of “Royal Softdrinks”. The giant company filed a suit against the provincial factory, claiming that “Royal” was losing market share in the region because consumers could not distinguish the logos of the Nepomuceno’s “Reyna” from San Miguel’s “Royal”—as both brands started with a capital “R” with a similar curly “y” treatment. The case was amicably settled, with the Nepomucenos agreeing to re-spell their brand to “Reina”.

But the family’s softdrink business was fated to falter from the start. The bottles alone, imported from Belgium, cost 8 centavos a piece, while with contents—5 centavos. But since the business brought jobs to locals, the Nepomucenos could not bear to close it down.

However, in the early days of the Japanese Occupation, the Nepomucenos evacuated to Tarlac and upon their return, they found their machines destroyed and almost all the bottles smashed. They had no choice but to shut down the business permanently. Apparently, one bottle survived the rampage of Japanese soldiers, and today, this small, greenish bottle with the name “Reyna” in relief, has truly become the “Queen” of bottle collectibles.