SARMIENTO-PANLILIO NUPTIALS. The celebrated wedding of noted town beauty Luz Sarmiento and businessman Jose Panlilio took place at the grand San Guillermo Church in April 1934. They built their home in Bacolor and became active participants in various socio-civic activities of the town.

The Commonwealth years were a period of plenty for Bacolor and many of its residents, already known for their artistry and gentility, enjoyed new-found affluence reaped mostly from their rich agricultural lands. The Panlilios were among the most prominent, led by the patriarch Don Domingo Panlilio who took special pride in his children: Jose (Pepe), Francisco (Quitong) and Encarnacion (Carning). Unfortunately, they would be orphaned early.

On the other hand, were the more modest Sarmientos-- Cipriano and Ines (nee Lugue of Apalit)—who would be blessed with girls noted for their beauty, but most especially their elder daughter named Luz (born 23 July 1934). Lucing’s grade school years were spent at the local St. Mary’s Academy, after which she attended Assumption Academy in neighboring San Fernando for her higher education.

While a student of that school, Luz was elected Miss Bacolor 1933 and was a runner-up at the Miss Pampanga 1933 search. In 1934, the premiere magazine, The Philippine Free Press, conducted its own Miss Free Press search , and Luz was named Miss Pampanga, based on pictures sent to the publication. That same year, however, she again decided to try her luck at the Manila Carnival of 1934, with the full support of her newspaper-sponsor, La Opinion.

With such credentials, it was no wonder then that young men came in droves to woo her. But in the end, she chose a kabalen—the tall and very eligible Jose “Peping” Panlilio, no less.

Lucing and Peping were married at the San Guillermo Church on April 1934. Sister Angelina stood as the maid of honor, while Encarnacion and Araceli Sarmiento stood as bridesmaids. Best Man was Peping’s brother, Francisco, attended by ushers Aquilino Reyes and Mariano Liongson, The principal sponsors included Mrs. Sotero Baluyut (the governor’s wife) and Dr. Clemente Puno, who was the sanitary division president of Guagua, Bacolor and Sta. Rita at that time.

The couple made their home in Bacolor, taking residence in the magnificent Panlilio-Santos mansion, which featured painted portraits of the family’s ancestors (Jose Leon Santos and 2nd wife Ramona Joven) by the 19th century master Simon Flores.They had one child, Jesus Nazareno, was born on 9 January 1935.

The couple’s prominence grew as their businesses expanded that came to include landholdings and various commercial estates. Peping passed away in 1961, but Lucing carried on. She became a well-respected community leader known for her business savvy that enabled her to sustain and grow the family enterprise through War and illness.

As an ardent devotee of the La Naval Virgin of Bacolor, it was Lucing who propagated further this Marian devotion, improving the image with gifts of vestments, jewelry and carroza. To this day, "La Naval de Bacolor" is an annual religious spectacle that Marian devotees eagerly await. The grand dame of Bacolor passed away in August 1998.

Today, at the Museo De La Salle in Dasmariñas, Cavite, several rooms in the re-created Santos-Joven Panlilio House, which was saved from the lahar inundation by her grandson Jose Ma. Ricardo, are dedicated to their memory.

Pampanga, a province of Central Luzon in the Philippines, was established along the banks ("pampang") of a great river that was to shape its history-the Rio Grande de la Pampanga. Travelers who passed the river's way brought home stories of a land with a majestic mountain jutting from its navel, a place of scenic wonders, boundless resources and magnificent townscapes, peopled by a proud brown race. What other magical views could our forefathers have seen from this river's fabled "pampang"?

Sunday, December 16, 2012

Tuesday, December 11, 2012

*318. JOSE BUMANLAG DAVID: Painting Immortality

THE RETURN OF THE NATIVE. Early work of Jose Bumanlag David, painted in his 20s, as it appeared as a reproduction color print on Graphic Magazine in 1934. David was well-known for portraits of ethnic types, the fad of the times. but eventually became even more popular when he painted portraits of ordinary people at his shop near Clark Air Base

In the field of portraiture—where technical accuracy, mastery of light, tone and mood are required of the artist, one Kapampangan painter stands out—Jose Bumanlag David. Though he painted a variety of subjects throughout his long, prolific career, it is in portraiture that he found recognition, thanks largely to his American clientele.

My first brush with this accomplished visual artist was in the mid 90s, when I went to a art gallery in Balibago near the Abacan Bridge to have some prints framed. There, amidst the clutter of acrylic paintings and kitschy copies of European masterpieces, I found a small vintage ethnic painting so popular in that era, signed in graceful cursive script by one “Jose B. David, 1955”. It is a portrait of a young lakan, perhaps still in his teens, attired in tribal clothes, complete with a potong, necklaces and earrings.

The portrait captured the likeness of a proud, handsome royal right down to his earthen complexion and his stare that pierces through you despite a half-smile. The gallery owner was just too happy to part with the old painting for Php 200, and my only regret was not asking if this portrait had a matching “lakambini”, as it was the custom of artists in those days to paint “his and hers”paintings.

Thus began my search to know more about this gifted painter—Jose Bumanlag David. The future visual artist was born in Mexico, Pampanga on 26 July 1909. His early schooling began at the Mexico Elementary School and San Fernando Intermediate School. He then enrolled in Pampanga’s premiere high school—the Pampanga High School from where he graduated in 1929. In college, he chose to take up Fine Arts—a course that was not exactly desirable in those days; painting was not considered a profession and painres were treated with disdain (“wala kang mapapala sa hampaslupang ýan!”).

Nevertheless, David went on to enter the U.P. School of Fine Arts where he quickly made a name for himself as a promising art student by winning medals in various inter-school art contests. He graduated in 1934 and started painting popular subjects like common folks in rural settings, historical tableaus and ethnic scenes. His paintings caught the eyeof leading dailies, and his artworks were featured regularly on the glossy, color sections of the Philippine Free Press. In 1939, Jose David and Wenceslao Garcia held a joint exhibition at the U.P. Library Gallery which drew much praise from the public.

Soon, his works were being collected by noted art connoisseurs like Jorge Vargas. At the 1941 National Art Competition held by the University of Santo Tomas, David won 2nd Honorable mention for his ”Presentation of the Santo Nino to the Queen of Cebu”(Religious Category) and 3rd Honorable Mention for his “Man of the Soil”(Filipiniana Category). His output was so prodigious that pre-World War II, his works could be found in the classrooms of many Manila schools and at the offices of the Department of Education, health and Public Welfare. After the War, he re-established his profession by relocating in Angeles, where he conducted art classes at the Clark Air Base.

It was to be a long and fruitful stay—thirty years in fact, from 1947 to 1977. He took a break to finish a management course in 1964 at the Air Force Institute at Gunter Air Base University, Alabama. Afterwhich, he established his studio near the base and, beginning in 1971 till 1982, he gave private art classes to bored American wives of U.S. military personnel and their other family members. One of his last one-man show was held in 1990 at Galerie Andrea in 1990. Many of his portraits of American military officers used to hang in various Clark Air Base buildings and those of Filipino heroes at the Scottish Rite Temple.

After his death, his studio closed but many galleries around the city continued to carry some of his prized artworks that were popular as tourist souvenirs. Today, his paintings rarely surface in the local market. A few pieces could still be seen at the U.P. Filipiniana Museum, part of the vast Jose B. Vargas art collection donated to the state university. Jose Bumanlag David, the master portraitist who so deftly immortalized on canvass the likenesses of thousands of faces—young, old, man, woman, Filipino, American—has also earned immortality himself as Pampanga’s most accomplished portraitist.

Monday, November 26, 2012

*317. DR. RAFAELITA HILARIO-SORIANO: Kapampangan Scholar, Educator, Diplomat

DR. RAFAELITA HILARIO-SORIANO, Compleat woman personified. This san Fernando-born Kapampangan was an educator, a scholar, a researcher, a historian, a cultural advocate, a diplomat--excelled in all her chosen fields.

A woman who broke barriers in her time, Dr. Rafaelita Hilario-Soriano was first and foremost, a Kapampangan erudite whose impressive background, diverse experience and love of local culture set her high above the rest, enabling her to assumer and master many roles—from an acclaimed educator, writer-historian, socio-civic leader to an ambassador to the world.

Her parentage foretold of an illustrious future: she was born in San Fernando on 2 July 1915 to Judge Zoilo J. Hilario of Bacolor and Trinidad Vasquez of Hinigiran, Negros Occidental. Hilario, an eminent zarzuelista in his hometown, would rise to become an important figure in Philippine judiciary and politics—he would become a judge of the Court of the First Instance and a congressman.

Rafaelita would grow up in the capital town with siblings Evangelina (herself, a leading light of Kapampangan language and culture) Tiburcio, Ofelia, Efrain and Ulysses. In San Fernando, Rafaelita first attended Santos Private School, and moved to Pampanga High School for her secondary studies.

Upon graduation, she went to Manila with her widowed grandmother, Dña. Adriana Sangalang vda. De Hilario, who put up a boarding school for Bacolor students. She enrolled at the Philippine Women’s University and obtained an A.B. Political Science, minor in History in 1936. She next went to U.P. for her Master’s degree in the same field of study, which she completed in 1938.

With her brilliant academic record, she was soon swamped with teaching offers. She became an instructor at Sta. Isabel College, Holy Ghost College, and National University. In 1940, however, she was offered to organize the Liberal Arts College at the Laguna Academy in San Pablo City. She went there together with Miss Paulina Gueco (sister of the late Sen. Jose Diokno) and became the dean of the college.

Her stay in San Pablo proved to be short-lived as the next year, she won a Levi Barbour Scholarship at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Rafaelita’s supposed two year –stay in the United States was extended due to the second World War. She made use of the extra time by earning a second Master of Arts in Public Administration.

It was about this time that she decided that the insulated life of an academician was not entirely proper when her country was at war, so she packed her bags for Washington, where she took a job as a research assistant in charge of the Philippine Section, Military Intelligence Division of the War Department. She held on to this job until the war came to an end with the surrender of Japan.

Comforted by the thought that her family in Pampanga was now safe, Rafaelita returned to Michigan to get her doctorate. She earned her Ph.D. with her well-researched thesis about the role of propaganda in the Japanese occupation in the Philippines. While completing her higher studies, Rafaelita found time to wed Dr. Jesus Soriano, a gastro-enterologist, at St. Mary’s Chapel in Ann Arbor.

In 1948, Rafaelita—with husband and daughter Maria Elena in tow—finally set sail for the Philippines. Upon her comeback, Rafaelita became a lecturer at her alma mater, University of the Philippines, Lyceum and at Arellano University. The indefatigable Rafaelita founded the Philippine Civic Organization. She was also elected as National Vice President of the YMCA, chairman of the Political Action Committee and Director of the Philippine-Michigan Club. On the side, she also worked at the Department of Foreign Affairs, which put her already multi-facetted career on yet another path—Foreign Service.

Rafaelita proved her mettle by being named as a Chairman of the Information, Culture, Education and Labor Activities Committee of the SEATO (Southeast Asian Nations Treaty Organization)--only the second woman to preside over an international conference. Her contribution was immediately recognized by the United Nations Association of the Philippines (UNAP).

In 1970, she was appointed as Secretary-General of the SEATO Council of Minister’s Meeting in Manila, which she handled with utmost proficiency. This led to her being named as an Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Israel, where she was warmly received by Pres. Salman Zhazar. She thus joined a few, but elite number of early women ambassadors like Trinidad Fernandez and Pura Santillan-Castrence, who blazed the trails towards the feminization of diplomacy.

When she retired from government service, she took up her pen to write several acclaimed books about Pampanga’s rich history: Shaft of Light (1991), Women in the Philippine Revolution (1996, editor), The Pampangos (1999). In March 2000, Rafaelita Hilario-Soriano was named as one of the 100 Filipino Women of the Millenium, a well-deserved accolade. This accomplished Kapampangan who wore many hats, assumed many roles and mastered them all, passed away on 1 January 2007.

A woman who broke barriers in her time, Dr. Rafaelita Hilario-Soriano was first and foremost, a Kapampangan erudite whose impressive background, diverse experience and love of local culture set her high above the rest, enabling her to assumer and master many roles—from an acclaimed educator, writer-historian, socio-civic leader to an ambassador to the world.

Her parentage foretold of an illustrious future: she was born in San Fernando on 2 July 1915 to Judge Zoilo J. Hilario of Bacolor and Trinidad Vasquez of Hinigiran, Negros Occidental. Hilario, an eminent zarzuelista in his hometown, would rise to become an important figure in Philippine judiciary and politics—he would become a judge of the Court of the First Instance and a congressman.

Rafaelita would grow up in the capital town with siblings Evangelina (herself, a leading light of Kapampangan language and culture) Tiburcio, Ofelia, Efrain and Ulysses. In San Fernando, Rafaelita first attended Santos Private School, and moved to Pampanga High School for her secondary studies.

Upon graduation, she went to Manila with her widowed grandmother, Dña. Adriana Sangalang vda. De Hilario, who put up a boarding school for Bacolor students. She enrolled at the Philippine Women’s University and obtained an A.B. Political Science, minor in History in 1936. She next went to U.P. for her Master’s degree in the same field of study, which she completed in 1938.

With her brilliant academic record, she was soon swamped with teaching offers. She became an instructor at Sta. Isabel College, Holy Ghost College, and National University. In 1940, however, she was offered to organize the Liberal Arts College at the Laguna Academy in San Pablo City. She went there together with Miss Paulina Gueco (sister of the late Sen. Jose Diokno) and became the dean of the college.

Her stay in San Pablo proved to be short-lived as the next year, she won a Levi Barbour Scholarship at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Rafaelita’s supposed two year –stay in the United States was extended due to the second World War. She made use of the extra time by earning a second Master of Arts in Public Administration.

It was about this time that she decided that the insulated life of an academician was not entirely proper when her country was at war, so she packed her bags for Washington, where she took a job as a research assistant in charge of the Philippine Section, Military Intelligence Division of the War Department. She held on to this job until the war came to an end with the surrender of Japan.

Comforted by the thought that her family in Pampanga was now safe, Rafaelita returned to Michigan to get her doctorate. She earned her Ph.D. with her well-researched thesis about the role of propaganda in the Japanese occupation in the Philippines. While completing her higher studies, Rafaelita found time to wed Dr. Jesus Soriano, a gastro-enterologist, at St. Mary’s Chapel in Ann Arbor.

In 1948, Rafaelita—with husband and daughter Maria Elena in tow—finally set sail for the Philippines. Upon her comeback, Rafaelita became a lecturer at her alma mater, University of the Philippines, Lyceum and at Arellano University. The indefatigable Rafaelita founded the Philippine Civic Organization. She was also elected as National Vice President of the YMCA, chairman of the Political Action Committee and Director of the Philippine-Michigan Club. On the side, she also worked at the Department of Foreign Affairs, which put her already multi-facetted career on yet another path—Foreign Service.

Rafaelita proved her mettle by being named as a Chairman of the Information, Culture, Education and Labor Activities Committee of the SEATO (Southeast Asian Nations Treaty Organization)--only the second woman to preside over an international conference. Her contribution was immediately recognized by the United Nations Association of the Philippines (UNAP).

In 1970, she was appointed as Secretary-General of the SEATO Council of Minister’s Meeting in Manila, which she handled with utmost proficiency. This led to her being named as an Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Israel, where she was warmly received by Pres. Salman Zhazar. She thus joined a few, but elite number of early women ambassadors like Trinidad Fernandez and Pura Santillan-Castrence, who blazed the trails towards the feminization of diplomacy.

When she retired from government service, she took up her pen to write several acclaimed books about Pampanga’s rich history: Shaft of Light (1991), Women in the Philippine Revolution (1996, editor), The Pampangos (1999). In March 2000, Rafaelita Hilario-Soriano was named as one of the 100 Filipino Women of the Millenium, a well-deserved accolade. This accomplished Kapampangan who wore many hats, assumed many roles and mastered them all, passed away on 1 January 2007.

Monday, November 12, 2012

*316. Gotta Travel On: MACARTHUR HIGHWAY

THE LONG AND WINDING ROAD. The main road in Dau, circa 1915. By the the Commonwealth years, the Americans had built 220 kms. of concrete roads in Pampanga, ending in Dau., to accommodate Pampanga's motor vehicles, which ranked 5th in number, nationwide.

In the early ‘60s, before NLEX and SCTEX, the only way to travel to Manila from Pampanga was by the old Manila North Road—or MacArthur Highway, as it was more popularly known to motorists. Named after Lieutenant General Arthur MacArthur, Jr, the military Governor-General of the American-occupied Philippines from 1900 to 1901, the long highway stretched from La Union, to the provinces of Central Luzon (Pangasinan, Tarlac, Pampanga, Bulacan) and finally to the city of Manila. Under the American Regime, road-building was at its most brisk, and by 1933, Pampanga had over 220.1 kms. of 1st class roads, ending north in Dau.

As a child, I remember some of those trips so vividly well as they were moments to look forward to. After all, it was not very often that kids like us were taken out for long rides to the big city. So, every time our parents announced that we would be going to Manila, we knew the occasion would be something special—a family reunion, a fiesta in Blumentritt or perhaps, a visit to our cousins in Herran (now Pedro Gil St).

Our trips were always scheduled on weekends, and as early as Friday morning, our parents would already be preparing for the trip. Dad would be checking on and tuning up the Oldsmobile, while Ma would be looking for tin cans that would serve as our emergency “orinola” (urinal) or vomit bag, in case of motion sickness or incontinence. We always left in the early dawn, with most of us still drowsy and asleep--no later than 5 a.m. , as mandated by my ever-punctual Dad. With water bottles and half-a-dozen or so hardboiled eggs, we thus began our 99 km. journey to the capital city.

From our house in Sta. Ines, Mabalacat, my Dad would drive out onto the main highway, towards Dau and Angeles. Past those familiar places, we proceeded to the capital town, San Fernando, with Manila still 57 kms. away. We would just coast along till San Vicente in Apalit, the highway a bit dusty and bumpy at this point. Upon hitting the rickety bridge of Calumpit, I knew we were no longer in Pampanga—we were in the Tagalog province of Bulacan, home of my favourite ensaimada de Malolos. I knew, because we would always stopped in the capital town to buy these pastries, cheese-topped and overloaded with red eggs.

From Malolos, it was off to Guiguinto, a town with an intriguing name for a 6 year old—I had often envisioned it either overrun with salaginto beetles or sparkling with golden lights. I remember the tall electric posts that lined the highway as we approached Bigaa, Tabang, then Bocaue. I once overheared adults talking about the “kabarets”of Bocaue in hushed whispers, but I've never seen girls dancing on the highway! Fixing my gaze on the world outside through the car window, i would see early risers buying bread from bakeries, Mobilgas stations and their lighted signs wishing travellers “Pleasant motoring!, Baliuag buses picking up passengers, ricefields that stretched as far as the eyes can see.

I would already be impatient and bored at this time, even as the features of the bucolic towns of Marilao and Meycauayan (where are the bamboo trees?) loomed clearer with the rising sun. But all this fretting would stop as soon as we got a glimpse of this tall obelisk in the distance—the Monumento—a landmark that told me that, at last, we were in Manila. If we were going to Sta. Cruz, we would veer towards the Monumento, gawking at the sculpted images of the revolucionarios and the doomed Gomburza padres as we made a half-loop towards Manila proper. After some two hours of driving, we did it--the “promdis” have finally arrived!

In the early ‘60s, before NLEX and SCTEX, the only way to travel to Manila from Pampanga was by the old Manila North Road—or MacArthur Highway, as it was more popularly known to motorists. Named after Lieutenant General Arthur MacArthur, Jr, the military Governor-General of the American-occupied Philippines from 1900 to 1901, the long highway stretched from La Union, to the provinces of Central Luzon (Pangasinan, Tarlac, Pampanga, Bulacan) and finally to the city of Manila. Under the American Regime, road-building was at its most brisk, and by 1933, Pampanga had over 220.1 kms. of 1st class roads, ending north in Dau.

As a child, I remember some of those trips so vividly well as they were moments to look forward to. After all, it was not very often that kids like us were taken out for long rides to the big city. So, every time our parents announced that we would be going to Manila, we knew the occasion would be something special—a family reunion, a fiesta in Blumentritt or perhaps, a visit to our cousins in Herran (now Pedro Gil St).

Our trips were always scheduled on weekends, and as early as Friday morning, our parents would already be preparing for the trip. Dad would be checking on and tuning up the Oldsmobile, while Ma would be looking for tin cans that would serve as our emergency “orinola” (urinal) or vomit bag, in case of motion sickness or incontinence. We always left in the early dawn, with most of us still drowsy and asleep--no later than 5 a.m. , as mandated by my ever-punctual Dad. With water bottles and half-a-dozen or so hardboiled eggs, we thus began our 99 km. journey to the capital city.

From our house in Sta. Ines, Mabalacat, my Dad would drive out onto the main highway, towards Dau and Angeles. Past those familiar places, we proceeded to the capital town, San Fernando, with Manila still 57 kms. away. We would just coast along till San Vicente in Apalit, the highway a bit dusty and bumpy at this point. Upon hitting the rickety bridge of Calumpit, I knew we were no longer in Pampanga—we were in the Tagalog province of Bulacan, home of my favourite ensaimada de Malolos. I knew, because we would always stopped in the capital town to buy these pastries, cheese-topped and overloaded with red eggs.

From Malolos, it was off to Guiguinto, a town with an intriguing name for a 6 year old—I had often envisioned it either overrun with salaginto beetles or sparkling with golden lights. I remember the tall electric posts that lined the highway as we approached Bigaa, Tabang, then Bocaue. I once overheared adults talking about the “kabarets”of Bocaue in hushed whispers, but I've never seen girls dancing on the highway! Fixing my gaze on the world outside through the car window, i would see early risers buying bread from bakeries, Mobilgas stations and their lighted signs wishing travellers “Pleasant motoring!, Baliuag buses picking up passengers, ricefields that stretched as far as the eyes can see.

I would already be impatient and bored at this time, even as the features of the bucolic towns of Marilao and Meycauayan (where are the bamboo trees?) loomed clearer with the rising sun. But all this fretting would stop as soon as we got a glimpse of this tall obelisk in the distance—the Monumento—a landmark that told me that, at last, we were in Manila. If we were going to Sta. Cruz, we would veer towards the Monumento, gawking at the sculpted images of the revolucionarios and the doomed Gomburza padres as we made a half-loop towards Manila proper. After some two hours of driving, we did it--the “promdis” have finally arrived!

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

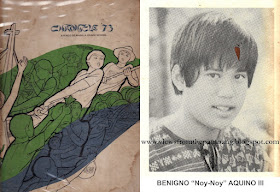

*315. His Grade School Yearbook: PRES. NOYNOY AQUINO III

A CHRONICLE OF HIS YOUTH. The future president of the Republic of the Philippines, as a 13 year old grade school graduate of Ateneo Grade School, Section Xavier, in 1973.

Thirty nine years ago, the future president of the Philippines graduated from the Ateneo de Manila University, just a year after the imposition of Martial Law. As seen from his grade school yearbook ("Chronicle"), Benigno Simeon Aquino III (b. 8 February 1960) seemed like any ordinary kid in the neighbourhood, on the verge of teenhood. Schoolmates remember him as a quiet, introverted boy, but as the son of Marcos’s most formidable opposition, Ninoy, he must have been cautioned to keep a low profile; the Martial Law years were undoubtedly a difficult period for the Aquinos.

As one can see, there is no listing of Noynoy’s school activities—no varsity football, no drama guild, no basketball teams, no membership in any clubs. A quick scan of his school annual revealed the young, eager faces of his batchmates who, today, are familiar names in Philippine society. There’s the late Alfie Anido who died under mysterious circumstances at the height of his fame as a movie star, the future designer Pepito Albert, as well as the future senator, Teofisto Guingona III.

Noynoy would stay on in Ateneo until his college years, earning an Economics degree in 1981 (one of his professors was Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo). He joined his exiled father with the rest of the family in the United States until he came back to the Philippines in 1983, after his father’s assassination. After working in the private sector, he plunged headlong into politics, first as as an elected member of the House of Representatives representing Tarlac in 1998 (re-elected in 2001 and 2004) and as a Senator, elected in 2007.

Following the death of his mother, Cory C. Aquino in 2009, Noynoy heeded the people’s call by joining the presidential race under the Liberal Party. He would go on to become the highest executive of the land, our country’s 15th president in June 2010, trouncing other bets like the popular Erap Estrada, Manny Villar and Gilbert Teodoro, an Aquino relative.

With his victory, Noynoy became the 3rd youngest presidential-elect of the Philippines, after Magsaysay and Marcos, and our very first bachelor-president. The quiet boy with bangs who would rather be alone, would also make history for his alma mater by becoming the first Atenean to become the President of the Republic of the Philippines.

Thirty nine years ago, the future president of the Philippines graduated from the Ateneo de Manila University, just a year after the imposition of Martial Law. As seen from his grade school yearbook ("Chronicle"), Benigno Simeon Aquino III (b. 8 February 1960) seemed like any ordinary kid in the neighbourhood, on the verge of teenhood. Schoolmates remember him as a quiet, introverted boy, but as the son of Marcos’s most formidable opposition, Ninoy, he must have been cautioned to keep a low profile; the Martial Law years were undoubtedly a difficult period for the Aquinos.

As one can see, there is no listing of Noynoy’s school activities—no varsity football, no drama guild, no basketball teams, no membership in any clubs. A quick scan of his school annual revealed the young, eager faces of his batchmates who, today, are familiar names in Philippine society. There’s the late Alfie Anido who died under mysterious circumstances at the height of his fame as a movie star, the future designer Pepito Albert, as well as the future senator, Teofisto Guingona III.

Noynoy would stay on in Ateneo until his college years, earning an Economics degree in 1981 (one of his professors was Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo). He joined his exiled father with the rest of the family in the United States until he came back to the Philippines in 1983, after his father’s assassination. After working in the private sector, he plunged headlong into politics, first as as an elected member of the House of Representatives representing Tarlac in 1998 (re-elected in 2001 and 2004) and as a Senator, elected in 2007.

Following the death of his mother, Cory C. Aquino in 2009, Noynoy heeded the people’s call by joining the presidential race under the Liberal Party. He would go on to become the highest executive of the land, our country’s 15th president in June 2010, trouncing other bets like the popular Erap Estrada, Manny Villar and Gilbert Teodoro, an Aquino relative.

Monday, October 22, 2012

*314. THE PASSION OF NEGRITA MAGDALENA

DARK DECEPTION. Negrita Magdalena (with husband Felix) was a loyal companion to a rich Bambanense woman who eventually willed her property upon her death. Unschooled and illiterate, Magdalena found herself in the middle of legal intrigues, stirred by her mistress's relative who claimed she was ineligible to inherit such great wealth.

The controversial Dean C. Worcester once caused an indignant stir among Filipinos when he wrote about the existence of slavery and peonage in the Philippines. The charge did not sit well on Filipinos, which prompted Mr. Worcester to cite the story of a Negrita named Magdalena, and her extraordinary relationship with her mistress, Dña. Petrona David. His intent, he clarified, was not to condemn, but to praise their inspiring story, that began in the border town of Bamban, in Tarlac province.

Doña Petrona David was a prominent resident of this town, a widow with no children. One day, she chanced upon a Negrito selling “bulu” ( a bamboo specie) in town. She not only bought the bamboo but also took a fancy to his 5 children—3 girls and 2 boys-- who had tagged along with their father. The kind doña singled out the young Magdalena, a true child of the mountains and the wilderness of Tarlac.

Magdalena was thus introduced to Dña. Petrona, and from the day on she would come to her house to help and run errands for her. When her parents died, the Bamban lady took the 7-year old Magdalena to her house and had her baptized. The illiterate Negrita thus lived with her, dutifully serving her needs, until her mistress got terminally sick.

Dña. Petrona died on 31 October 1919 and left behind property valued at Php15,000, a substantial sum in those days. But six months before her demise, Dña. Petrona had executed a will, bequeathing one third of her property to her trusted Magdalena, whom she had come to regard as her own daughter. Such was her generosity because, to use the words of her last will and testament “she has rendered me great service, serving me with loyal and sincere love, since she was baptized, and never separating herself from my side from that time up to the present date”.

There was a practical reason too, why the well-to-do lady did not leave all her property to her nearest relatives.”I know them as spendthrifts”, she noted, an observation she put in her will; she left a third of it to them anyway. The remaining 1/3 of her property was given to Don Pablo Rivera, manager of the David estate. Don Pablo was also named as administrator of the will. All hell broke loose as the David relatives, as expected, contested the legality of the will, and they pursued the case for two years—all the way up to the Supreme Court. But on 24 June 1922, the highest tribunal of the land declared the will, legal, authentic and binding.

You would think that this decision would have put closure to Magdalena’s woes so she could finally enjoy her just reward. But as the poor girl was unschooled, and unlettered, intrigues followed her wherever she went. Bambanenses could not understand why the Negrita should not be divested of her legacy due to her ignorance. People wagged their tongues to ask: “what would she do with the money and property anyway?”

But little did they know that Magdalena’s one extraordinaty expense is the Php70 that she shells out on the anniversary of her mistress’ death—to buy candles which are lit in her honor, and to pay for the little gathering in the house where prayers are said in memory of her adoptive mother. Every year, the Negrita alone remembers the memory of the late lady.

Fortunately for Magdalena, Judge Juan Sumulong came to her rescue in 1925. Sumulong was known for being an upright lawyer and he vowed to defend her interests as her guardian. Meanwhile, the administrator of the will has seen to it that apparently and legally, the property willed to the Negrita should become his own property too. We do not know the resolution of this case as this account, which was covered by the Philippine Free Press, ends here, a cliff hanger story of deception and trickery, with the clear intent to despoil the poor Negrita Magdalena of her just and rightful legacy.

Monday, October 15, 2012

*313. PATSY: Tawag ng Tanghalan's Hostess with the Mostest

PATSY PATSOTSAY. The loveable, laughable Patsy Mateo, from Lubao, is most well-known for her long association with perhaps, the greatest talent search in Philippine TV history--Tawag ng Tanghalan.

One comedienne who created one of the most iconic characters in Philippine movies based on her provincial background was the loveable Patsy. As the bumbling, hysterical Patsy Patsotsay, she would often spew out Kapampangan non-stop when caught in a fix.

This loveable, all-around entertainer with Lubao roots, come from the same town that nurtured the talents of movie greats Rogelio de la Rosa, and Jaime de la Rosa and Gregorio Fernandez.

She was born as Pastora Mateo on 12 April 1916, in Sta. Elena, Tondo, the child of Alejandro Mateo, who worked in a stall at the local market. As a youngster, Patsy was given the nickname “Lapad”, in reference to her flat nose.

Even under the watchful eye of a very old-fashioned father, Patsy grew up breaking house rules to follow her heart’s desire. She was but 6 when she caught the Lou Borromeo variety show performing in a theater along Rizal Avenue. She broke into the theatre unnoticed via the back stage. Patsy was immediately smitten by the smell of the greasepaint and the roar of the crowd.

In 1924, she was in 2nd grade at Magdalena Elementary School when she saw and answered an ad about chorus girls being wanted at the Savoy Theater, just a walk away from Clover Theater. Together with her sister Rosa, she auditioned –and passed, until her parents discovered her adventure. John C. Cooper, the Savoy Theater, had given everyone of his troupe a five peso loan—which Patsy and Rosa proudly turned over to their father. The two truants were given a sound trashing, but they kept going back to the stage anyway. Eventually, the Mateo elders relented and allowed the youngsters to pursue their showbiz interest.

Patsy was just eleven when she joined a group of entertainers to tour Hawaii—along with Diana Toy, Sunday Reantazo, and saxophone player, Baclig. She was gone for a full year, but upon her return in 1928, she was immediately taken in as a feature singer at Tom’s Oriental Grill in Sta. Cruz. After 3 months, she was back dancing at the Savoy. In 1933, Patsy moved to the Palace Theater as a song-and-dance girl, performing alongside such veteran stalwarts as Katy de la Cruz, Tugo, Pugo and Amanding Montes.

From the bodabil house, Patsy broke into the movies in 1934, playing a supporting role in “Ang Dangal”. She rounded up the decade with roles in “Dasalang Perlas”(1938) and “Ruiseñor”(1939).

In 1939, while singing with comedienne Hanasan (Aurelia Alaldo) on stage, somebody in the audience informed her that her father had died. “I had to go on with the show my aching heart”, Patsy revealed in an interview. “Amidst all the buffoonery, tears were cascading down my cheeks.”

The War nipped Patsy’s budding film career, but in 1943, her showgirl career took a major turn when she became a comedienne. On one fateful day, Toytoy and comedy partner Gregorio Ticman had been scheduled to do an act together. As luck would have it, Toytoy fell ill and Patsy was asked to take over .She did a skit using her now famous Kapampangan-Tagalog dialogue—which brought down the house. A new star comedienne was born.

Patsy continued to entertain onstage during the years of the Japanese Occupation. As soon as thing settled down, she was back on screen in “Alaala Kita”(1946), The ‘50s and 60s decades marked her heyday as one of the country’s most favorite comedians. She appeared in the comedy hit, “Edong Mapangarap”(1950), opposite Eddie San Jose, “Bohemyo”, “Babae, Babae, at Babae Pa”(1952), “Basagulera”(1954).

Her biggest break, however, was when she was approached to be one of the hosts of a highly-popular singing contest that was sponsored by Procter and Gamble PMC : ”Tawag ng Tanghalan” which started on radio as “Purico’s Amateur Hour”. A unique feature of the program was the sounding of a bell that cut off the performance and signalled elimination of au unfortunate contestant. It had for its first grand champion, the Spanish-Filipino singer Jose Gonzales (Pepe Pimentel) who won with the song “Angelitos Negros”.

Patsy teamed up with Lopito when “Tawag”moved to television, a new medium that would also catapult the tandem to national fame. Patsy and Lopito had such charisma on TV, diffusing the pressure of competition with their humorous repartee in which they often argued and fought on-air.

As emcees, they also put contestants at ease with their light, easy patter, and the duo were witnessed to the meteoric rise of some of the “Tawag”winners through the years: Diomedes Maturan ( 1959), Kapampangan Cenon Lagman (1960), Nora Aunor (1968) and Edgar Mortiz.

Eventually, the TV show found its way to the silver screen in 1958 starring Susan Roces. Patsy supported the 1959 winner, Diomedes Maturan, by appearing in several of his movies, starting with “Private Maturan” (1959), “Detective Maturan” and “Prinsipe Diomedes at ang Mahiwagang Gitara”(1961). Even as she was becoming a household name on TV, Patsy continued to work the stage circuit, doing live acts in theaters like Clover, in Manila.

She was back in films in the 60s and among her most hilarious hits were “Juan Tamad Goes To Society”, “Manananggal vs. Mangkukulam” (1960), “Kandidatong Pulpol” (1961), “Triplets”(1961) and “The Big Broadcast” (1962). Patsy was also part of the celebrated group of seven bungling househelps (Aruray, Chichay, Menggay, Elizabeth Ramsey, Dely Atay-Atayan, Metring David were the other maids) in the blockbuster movie “Pitong Atsay” (1962) under dalisay Films and megged by Tony Santos. It chronicled the “naughty, nutty misadventures of 7 zany house maids, their lives and loves, in their guarded and unguarded moments”.

A sequel was hastily filmed on the heels of the movie’s success: “Ang Pinakamalaking Takas ng 7 Atsay”. TV kept Patsy busy in the 1970s; she played the role of the matriarch in the highly-rated comedy show “Wanted: Boarder”, opposite Pugo on Channel 2.

When Martial Law closed down the channel, the show reincarnated in Channel 5 as “Boarding House”, with practically the same cast. In 1975, Pugo and Patsy were the parents of Jay Ilagan in another hit sit-com on RPN 9, “My Son, My Son”. Then there was the short-lived, “Sila-Sila, Tayo-Tayo, Kami-Kami”, with Chichay.

In all her appearances, Patsy consistently remained true to her character—splicing Kapampangan words into her dialogues at every opportunity, speaking with that distinct “gegege”accent that became her trademark. The Patsy-Pugo tandem could have endured as another great comedy pair, but that ended with Pugo’s demise in 1978.

A few months after, the irrepressibly funny Lubeña—Patsy Mateo—passed away in 1979. When a Tawag ng Tanghalan retrospective show was produced by Procter and Gamble in 1985, comedienne Nanette Inventor (from Macabebe) portrayed her so effectively, that for a moment, it seemed that the wise-cracking hostess with the mostest--Patsy Patsotsay—had returned to conquer the stage she loved all her life.

One comedienne who created one of the most iconic characters in Philippine movies based on her provincial background was the loveable Patsy. As the bumbling, hysterical Patsy Patsotsay, she would often spew out Kapampangan non-stop when caught in a fix.

This loveable, all-around entertainer with Lubao roots, come from the same town that nurtured the talents of movie greats Rogelio de la Rosa, and Jaime de la Rosa and Gregorio Fernandez.

She was born as Pastora Mateo on 12 April 1916, in Sta. Elena, Tondo, the child of Alejandro Mateo, who worked in a stall at the local market. As a youngster, Patsy was given the nickname “Lapad”, in reference to her flat nose.

Even under the watchful eye of a very old-fashioned father, Patsy grew up breaking house rules to follow her heart’s desire. She was but 6 when she caught the Lou Borromeo variety show performing in a theater along Rizal Avenue. She broke into the theatre unnoticed via the back stage. Patsy was immediately smitten by the smell of the greasepaint and the roar of the crowd.

In 1924, she was in 2nd grade at Magdalena Elementary School when she saw and answered an ad about chorus girls being wanted at the Savoy Theater, just a walk away from Clover Theater. Together with her sister Rosa, she auditioned –and passed, until her parents discovered her adventure. John C. Cooper, the Savoy Theater, had given everyone of his troupe a five peso loan—which Patsy and Rosa proudly turned over to their father. The two truants were given a sound trashing, but they kept going back to the stage anyway. Eventually, the Mateo elders relented and allowed the youngsters to pursue their showbiz interest.

Patsy was just eleven when she joined a group of entertainers to tour Hawaii—along with Diana Toy, Sunday Reantazo, and saxophone player, Baclig. She was gone for a full year, but upon her return in 1928, she was immediately taken in as a feature singer at Tom’s Oriental Grill in Sta. Cruz. After 3 months, she was back dancing at the Savoy. In 1933, Patsy moved to the Palace Theater as a song-and-dance girl, performing alongside such veteran stalwarts as Katy de la Cruz, Tugo, Pugo and Amanding Montes.

From the bodabil house, Patsy broke into the movies in 1934, playing a supporting role in “Ang Dangal”. She rounded up the decade with roles in “Dasalang Perlas”(1938) and “Ruiseñor”(1939).

In 1939, while singing with comedienne Hanasan (Aurelia Alaldo) on stage, somebody in the audience informed her that her father had died. “I had to go on with the show my aching heart”, Patsy revealed in an interview. “Amidst all the buffoonery, tears were cascading down my cheeks.”

The War nipped Patsy’s budding film career, but in 1943, her showgirl career took a major turn when she became a comedienne. On one fateful day, Toytoy and comedy partner Gregorio Ticman had been scheduled to do an act together. As luck would have it, Toytoy fell ill and Patsy was asked to take over .She did a skit using her now famous Kapampangan-Tagalog dialogue—which brought down the house. A new star comedienne was born.

Patsy continued to entertain onstage during the years of the Japanese Occupation. As soon as thing settled down, she was back on screen in “Alaala Kita”(1946), The ‘50s and 60s decades marked her heyday as one of the country’s most favorite comedians. She appeared in the comedy hit, “Edong Mapangarap”(1950), opposite Eddie San Jose, “Bohemyo”, “Babae, Babae, at Babae Pa”(1952), “Basagulera”(1954).

Her biggest break, however, was when she was approached to be one of the hosts of a highly-popular singing contest that was sponsored by Procter and Gamble PMC : ”Tawag ng Tanghalan” which started on radio as “Purico’s Amateur Hour”. A unique feature of the program was the sounding of a bell that cut off the performance and signalled elimination of au unfortunate contestant. It had for its first grand champion, the Spanish-Filipino singer Jose Gonzales (Pepe Pimentel) who won with the song “Angelitos Negros”.

Patsy teamed up with Lopito when “Tawag”moved to television, a new medium that would also catapult the tandem to national fame. Patsy and Lopito had such charisma on TV, diffusing the pressure of competition with their humorous repartee in which they often argued and fought on-air.

As emcees, they also put contestants at ease with their light, easy patter, and the duo were witnessed to the meteoric rise of some of the “Tawag”winners through the years: Diomedes Maturan ( 1959), Kapampangan Cenon Lagman (1960), Nora Aunor (1968) and Edgar Mortiz.

Eventually, the TV show found its way to the silver screen in 1958 starring Susan Roces. Patsy supported the 1959 winner, Diomedes Maturan, by appearing in several of his movies, starting with “Private Maturan” (1959), “Detective Maturan” and “Prinsipe Diomedes at ang Mahiwagang Gitara”(1961). Even as she was becoming a household name on TV, Patsy continued to work the stage circuit, doing live acts in theaters like Clover, in Manila.

She was back in films in the 60s and among her most hilarious hits were “Juan Tamad Goes To Society”, “Manananggal vs. Mangkukulam” (1960), “Kandidatong Pulpol” (1961), “Triplets”(1961) and “The Big Broadcast” (1962). Patsy was also part of the celebrated group of seven bungling househelps (Aruray, Chichay, Menggay, Elizabeth Ramsey, Dely Atay-Atayan, Metring David were the other maids) in the blockbuster movie “Pitong Atsay” (1962) under dalisay Films and megged by Tony Santos. It chronicled the “naughty, nutty misadventures of 7 zany house maids, their lives and loves, in their guarded and unguarded moments”.

A sequel was hastily filmed on the heels of the movie’s success: “Ang Pinakamalaking Takas ng 7 Atsay”. TV kept Patsy busy in the 1970s; she played the role of the matriarch in the highly-rated comedy show “Wanted: Boarder”, opposite Pugo on Channel 2.

When Martial Law closed down the channel, the show reincarnated in Channel 5 as “Boarding House”, with practically the same cast. In 1975, Pugo and Patsy were the parents of Jay Ilagan in another hit sit-com on RPN 9, “My Son, My Son”. Then there was the short-lived, “Sila-Sila, Tayo-Tayo, Kami-Kami”, with Chichay.

In all her appearances, Patsy consistently remained true to her character—splicing Kapampangan words into her dialogues at every opportunity, speaking with that distinct “gegege”accent that became her trademark. The Patsy-Pugo tandem could have endured as another great comedy pair, but that ended with Pugo’s demise in 1978.

A few months after, the irrepressibly funny Lubeña—Patsy Mateo—passed away in 1979. When a Tawag ng Tanghalan retrospective show was produced by Procter and Gamble in 1985, comedienne Nanette Inventor (from Macabebe) portrayed her so effectively, that for a moment, it seemed that the wise-cracking hostess with the mostest--Patsy Patsotsay—had returned to conquer the stage she loved all her life.

Thursday, October 4, 2012

*312. THE GILDED AGE OF ALTARS

SOME KIND OF WAWA-NDERFUL. The altar and retablo mayor of Guagua Church, dedicated to the Immaculate Conception. The mesa altar and the sagrario are covered with precious frontals of beaten silver. Ca. 1915.

When Augustinian missionaries descended upon Pampanga, they lost no time embarking on building churches. This religious order—first to arrive with Legazpi’s expeditionary group in 1565—is credited with constructing the most number of churches in the country.

The first visitas were made from indigenous materials—nipa, bamboo, hardwood trees—but with grants from the Real Hacienda, income from church services, free labor from the system of polo y servicio, churches soon evolved and grew into magnificent structures, with lavish decorations that rivalled those of Europe.

Nowhere is this more evident in the main altars of old Pampanga churches. Apparently, Filipinos and Spaniards shared a common interest in the decorative arts; just 50 years after Manila’s foundation, it was noted that the progressive city had churches adorned with rich silk fabrics and altar fronts covered with expensive silver.

Indeed, the altar became the most outstanding feature of the church in terms of artistry and opulence, for they were designed to attract attention and direct the gaze of the devotee to the tabernacle that housed the Holy Eucharist. The sagrario (tabernacle) was flanked by gradas (tiered panels) where decorations like ramilletes ( bouquets of silver or wood) and silver candeleros (candle holders) were placed.

The altar mayor featured the mantel-covered mesa altar, on which the priest said Mass, his back towards the audience. The Second Vatican Council of 1962 made significant reforms in the conduct of liturgical services, including changes in the physical make-up of the altar space. Altar tables were moved to the foreground, so that priests can celebrate the Mass, facing the audience. Retained were the magnificent retablos behind the mesa altar, frontal structures carved with period decorations and designed with nichos to house santos of wood and ivory, as well as paintings and relieves (relief carvings) showing Biblical and other holy scenes—all meant as visual aids in the missionaries’ oral teachings and in their attempt to convert people to Christianity.

The churches of Pampanga reflected the spirit of this gilded age, the combined power and glory of Art and Faith serving a higher purpose. The church of Lubao for instance, has a retablo mayor carved in florid Baroque style, with Augustinian santos enshrined in niches, leading one admirer to write that it is ”one of the most sumptuous in the Islands”.

The Santiago Apostol Church in Betis, likewise, boasts of a baroque wooden retablo carved with the most refined details, and infused with rocaille motifs—shells, curlicues, sinuous floral patterns. Once installed in the central niche was the figure of the patron—St. James as a peregrine, or pilgrim, now replaced with the Risen Christ. Angels playing musical instruments are scattered about the retablo, with the all-seeing God the Father, lording it all.

The church of Bacolor, dedicated to San Guillermo and touted as Pampanga’s biggest church in 1897, once had rich silver works with beautifully-gold leafed altar. The sunken retablos have all been restored after the Pinatubo eruption—sans the real gold gilt. Apalit has an intricately ornamented altar surmounted by a dome, replicating the church’s signature dome feature. The altar of San Simon is carved with floral splendor, with the figure of the Holy Spirit hovering above. Sta. Rita’s claim to fame was once its gilded main altar, while that of Masantol had Renaissance style carvings. The ancient church of San Luis also has an impressive retablo done in baroque, while Guagua’s altar frontals were once adorned with beaten silver (pukpok), made from precious silver coins.

The grandeur of our altars have been somehow dimmed by the ravages of time and the cataclysmic workings of nature—floods, earthquakes, volcanic upheavals. But though begrimed with dust, covered in lahar and engulfed in flood waters, it is before these altars that we always fall on our knees, intone our prayers for succor and help--and find our faith again.

When Augustinian missionaries descended upon Pampanga, they lost no time embarking on building churches. This religious order—first to arrive with Legazpi’s expeditionary group in 1565—is credited with constructing the most number of churches in the country.

The first visitas were made from indigenous materials—nipa, bamboo, hardwood trees—but with grants from the Real Hacienda, income from church services, free labor from the system of polo y servicio, churches soon evolved and grew into magnificent structures, with lavish decorations that rivalled those of Europe.

Nowhere is this more evident in the main altars of old Pampanga churches. Apparently, Filipinos and Spaniards shared a common interest in the decorative arts; just 50 years after Manila’s foundation, it was noted that the progressive city had churches adorned with rich silk fabrics and altar fronts covered with expensive silver.

Indeed, the altar became the most outstanding feature of the church in terms of artistry and opulence, for they were designed to attract attention and direct the gaze of the devotee to the tabernacle that housed the Holy Eucharist. The sagrario (tabernacle) was flanked by gradas (tiered panels) where decorations like ramilletes ( bouquets of silver or wood) and silver candeleros (candle holders) were placed.

The altar mayor featured the mantel-covered mesa altar, on which the priest said Mass, his back towards the audience. The Second Vatican Council of 1962 made significant reforms in the conduct of liturgical services, including changes in the physical make-up of the altar space. Altar tables were moved to the foreground, so that priests can celebrate the Mass, facing the audience. Retained were the magnificent retablos behind the mesa altar, frontal structures carved with period decorations and designed with nichos to house santos of wood and ivory, as well as paintings and relieves (relief carvings) showing Biblical and other holy scenes—all meant as visual aids in the missionaries’ oral teachings and in their attempt to convert people to Christianity.

The churches of Pampanga reflected the spirit of this gilded age, the combined power and glory of Art and Faith serving a higher purpose. The church of Lubao for instance, has a retablo mayor carved in florid Baroque style, with Augustinian santos enshrined in niches, leading one admirer to write that it is ”one of the most sumptuous in the Islands”.

The Santiago Apostol Church in Betis, likewise, boasts of a baroque wooden retablo carved with the most refined details, and infused with rocaille motifs—shells, curlicues, sinuous floral patterns. Once installed in the central niche was the figure of the patron—St. James as a peregrine, or pilgrim, now replaced with the Risen Christ. Angels playing musical instruments are scattered about the retablo, with the all-seeing God the Father, lording it all.

The church of Bacolor, dedicated to San Guillermo and touted as Pampanga’s biggest church in 1897, once had rich silver works with beautifully-gold leafed altar. The sunken retablos have all been restored after the Pinatubo eruption—sans the real gold gilt. Apalit has an intricately ornamented altar surmounted by a dome, replicating the church’s signature dome feature. The altar of San Simon is carved with floral splendor, with the figure of the Holy Spirit hovering above. Sta. Rita’s claim to fame was once its gilded main altar, while that of Masantol had Renaissance style carvings. The ancient church of San Luis also has an impressive retablo done in baroque, while Guagua’s altar frontals were once adorned with beaten silver (pukpok), made from precious silver coins.

The grandeur of our altars have been somehow dimmed by the ravages of time and the cataclysmic workings of nature—floods, earthquakes, volcanic upheavals. But though begrimed with dust, covered in lahar and engulfed in flood waters, it is before these altars that we always fall on our knees, intone our prayers for succor and help--and find our faith again.

Monday, September 24, 2012

*311. BLESS THIS HOUSE

BE IT EVER SO HUMBLE. Angeles-born Msgr. Manuel V. Del Rosario and parish priest of San Roque Church of Blumentritt, Sta. Cruz, performs a house blessing for one of his parishioners. Ca. 1950s.

For many Kapampangans, a house is not a home unless it is transformed into a haven of comfort and safety, protected not just from the elements but from the malevolence of this world, where only the goodness of heart reigns. And, like all Filipinos, he takes the extra effort to ward of negative vibes, even before the blueprint is drawn. As such, building beliefs abound, which have, through the years, served as his guidelines in the construction of their dream residences.

First, there is the issue of the house location. A house should not be erected at a dead end street, for that conjures the image of a dagger pointing its way to doorway of the house. It is preferred that houses face the east, so that when one opens the windows, he catches the first rays of the sun, a positive beginning. Carpenters contracted to build houses were often required to have their tools blessed, invoking their patron San Jose, for guidance, safety and a job well done. In Betis, the instruments of San Jose’s carpentry trade are processioned by male teens together with his image, although not on his feast day, but on the Monday after Easter Sunday.

Master carpenters often had a say on the choice of materials to be used for house construction. Wooden posts should be perfect, devoid of nodes and holes, for it is believed that spirits lurk inside these tree parts. Before the first post is planted into the ground, religious medals and coins are dropped into the hole for divine protection. In rural areas, pig or chicken blood is smeared on house posts, a primitive custom done for the same reason.

Stairways should be oriented towards the east; floor planks should be nailed parallel to the steps of the stairs, not perpendicular. Ceiling boards and floor planks should be laid at right angles to each other, lest death overtakes the resident.

To ensure prosperity and avoid bad luck, the steps of the stairs are counted while intoning the words “Oro, plata, mata” (Gold, silver, death). The last step should end with either “Oro” or “Plata”, but never “Mata”. Again, coins are usually cemented on the bottom stair landing to attract wealth and plenty.

The most auspicious time to transfer into one’s finished house is during the time of a full moon. Tradition dictates that the first objects to be brought into the house are a religious statue and a jar of salt. Salt is sacred to many cultures and figures in many superstitious practices; its purifying and preservative qualities make the mineral a symbol of good and long life.

The house blessing itself, is a cause for major celebration. A priest is specially invited to bless the house, room by room, floor by floor, while candles are lit and prayers are said. The reverend goes around splashing Holy Water on the different sections of the house, followed by a retinue of guests and residents. At the end of the blessing, the master of the house throws coins to the guests, who scamper to pick them up. With that generous gesture comes a wish for a life of peace and prosperity under a sturdy roof, in a humble place we call home.

For many Kapampangans, a house is not a home unless it is transformed into a haven of comfort and safety, protected not just from the elements but from the malevolence of this world, where only the goodness of heart reigns. And, like all Filipinos, he takes the extra effort to ward of negative vibes, even before the blueprint is drawn. As such, building beliefs abound, which have, through the years, served as his guidelines in the construction of their dream residences.

First, there is the issue of the house location. A house should not be erected at a dead end street, for that conjures the image of a dagger pointing its way to doorway of the house. It is preferred that houses face the east, so that when one opens the windows, he catches the first rays of the sun, a positive beginning. Carpenters contracted to build houses were often required to have their tools blessed, invoking their patron San Jose, for guidance, safety and a job well done. In Betis, the instruments of San Jose’s carpentry trade are processioned by male teens together with his image, although not on his feast day, but on the Monday after Easter Sunday.

Master carpenters often had a say on the choice of materials to be used for house construction. Wooden posts should be perfect, devoid of nodes and holes, for it is believed that spirits lurk inside these tree parts. Before the first post is planted into the ground, religious medals and coins are dropped into the hole for divine protection. In rural areas, pig or chicken blood is smeared on house posts, a primitive custom done for the same reason.

Stairways should be oriented towards the east; floor planks should be nailed parallel to the steps of the stairs, not perpendicular. Ceiling boards and floor planks should be laid at right angles to each other, lest death overtakes the resident.

To ensure prosperity and avoid bad luck, the steps of the stairs are counted while intoning the words “Oro, plata, mata” (Gold, silver, death). The last step should end with either “Oro” or “Plata”, but never “Mata”. Again, coins are usually cemented on the bottom stair landing to attract wealth and plenty.

The most auspicious time to transfer into one’s finished house is during the time of a full moon. Tradition dictates that the first objects to be brought into the house are a religious statue and a jar of salt. Salt is sacred to many cultures and figures in many superstitious practices; its purifying and preservative qualities make the mineral a symbol of good and long life.

The house blessing itself, is a cause for major celebration. A priest is specially invited to bless the house, room by room, floor by floor, while candles are lit and prayers are said. The reverend goes around splashing Holy Water on the different sections of the house, followed by a retinue of guests and residents. At the end of the blessing, the master of the house throws coins to the guests, who scamper to pick them up. With that generous gesture comes a wish for a life of peace and prosperity under a sturdy roof, in a humble place we call home.

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

*310. POWER TO THE PAMPANGUEÑA!

PARTAKERS OF THE WOMEN'S CLUB PROGRAM, Guagua Elementary School. Women's Clubs sprouted in schools as well as in communities, organized by Kapampangan elites mainly for social interaction and for their civic advocacies. Dated Jan. 1931.

The selection of the first female (and second youngest) Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in the person of Maria Lourdes Sereno by Pres. Benigno Aquino Jr. underscores the great strides women have made in their chosen fields, breaking barriers and rewriting history in the process. Her acclamation as the chief magistrate of the country recalls the gender-transcending achievements of the Kapampangan woman, who have always played important roles in the local society, empowered and privileged like no other.

Long before the terms “equal rights” became battlecries of feminists, the daughters of Pampanga were already enjoying certain perks with regards to land ownership. Like their male counterparts, women inherited land from their parents which they could buy and sell should they chose to. They could retain the land even upon marriage and could bequeath these property to their children, independent of their husbands.

Indeed, even in a society where patriarchs seem to dominate, women were vice-husbands, taking on the head of the family role if the father was absent. Women shared responsibilities with their men, be it in the household or out in the farmlands, swamps and fishponds. Described by priest-historian Fray Gaspar de San Agustin as being “very brave and strong”—both masculine properties, Kapampangan women certainly were as capable as the opposite sex in the execution of their duties.

When new settlements and towns were being established, the Kapampangan women stood by her man. Mabalacat, which started as a forest clearing, may have been founded by the Negrito chief Garagan, but it was his wife, Laureana Tolentino, who became the town cabeza, the first known female head of a Pampanga municipality. Dña. Rosalia de Jesus is credited in history books as the co-founder of Culiat in 1796, the future city of Angeles, alongside her husband, Don Angel Pantaleon de Miranda. Similarly, Botolan in Zambales owes its existence to a woman, known only by the name Dña. Teresa of Mabalacat, who secured a permit in Manila to establish the town in 1819.

The earliest Filipino nuns were also Kapampangans, led by the virtuous Martha de San Bernardo, the first india to be accepted by the monastery of Sta. Clara (founded by Bl. Jeronima de la Asuncion in 1621) around 1633. The Recollect siblings, Mother Dionisia and Mother Cecilia Talangpaz are recognized as the second foundresses of a religious congregration in the Philippines. Half-Kapampangans, they trace their ancestry to the Pamintuans and Mallaris of Macabebe.

Meanwhile, the first female religious to set up an orphanage came from one of the richest families of Bacolor--Sor Asuncion Ventura. A Daughter of Charity, she used her inheritance to put up the Asilo de San Vicente de Paul in 1885. In the literary field, the first woman author was a Pampangueña from Bacolor, Dña. Luisa Gonzaga de Leon. She translated the Spanish religious work Ejercicio Cotidiano (Daily Devotion) into Kapampangan, which was published posthumously around 1844-45.

During the Philippine Revolution, Kapampangan women came in full force to aid the revolucionarios. Led by Nicolasa Dayrit, Felisa Dayrit, Felisa Hizon, Consolacion Singian, Encarnacion Singian, Marcelina Limjuco and Praxedes Fajardo, members of the Junta Patriotica de San Fernando and La Cruz Roja (Red Cross), they also sewed the flag of the Pampanga Batallion in December 1898. Female financiers of the movement included Teodora Salgado and Matea Rodriguez Sioco.

Nursing was still a new course offered at the Escuela de Enfermas of the Philippine General Hospital when Marcelina Nepomuceno (b. 9 Aug. 1881 to Ysabelo Nepomuceno and Juana Paras) enrolled with one of the earliest batches of students. She is known as the first Kapampangan Florence Nightingale. Sharing this honor is Dra. Francisca Galang, the first female Kapampangan medical doctor.

In agriculture and business, a realm often dominated by male hacenderos, the names of Dñas. Tomasa Centeno vda. De Pamintuan (Angeles), Teodora Salgado vda. De Ullman (San Fernando), Victoria Hizon vda. De Rodriguez (San Fernando), Epifania Alvendia vda. De Guanzon (Floridablanca), Donata Montemayor vda. De Vitug (Lubao) and Antonina Reyes vda. De Samson were held in esteem during the Commonwealth years. Widows all, they carried on the work of their late husbands—as sugar planters and entrepreneurs—with grit, hard work and devotion, to successful results.

In the same period, Women’s Clubs were organized by Pampanga matrons in Angeles, Bacolor and San Fernando, which counted Americans, teachers and army wives as members, for their socio-civic pursuits. Educational opportunities expanded with the establishments of colleges and universities. From the 20s to the 40s, elite families sent their daughters to schools in Europe and America, like Paz Pamintuan (daughter of Don Florentino Pamintuan) who finished her M.D. at the Woman’s Medical College in Philadelphia in 1925. Society girl Paquita Villareal was schooled in Hongkong and Germany, while Florencia Salgado went to Paris for her Arts degree. Today, some of the pillars of education are Kapampangan women—like Dr. Barbara Yap-Angeles, founder of Angeles University Foundation in 1962.

In 1976, a Kapampangan woman--Juanita Lumanlan Nepomuceno--broke new ground by becoming Pampanga's first female governor, a position that Lilia Pineda would win 34 years later. Lest we forget, two Kapampangan women have occupied the highest position of the land as Presidents of the Philippines: Corazon Cojuangco-Aquino of Tarlac (1986-1992) and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo of Lubao (2001-2004, re-elected 2004-2010).

All these accomplished names are proof positive that if you want the best man for the job, pick a woman. Better yet, pick a Kapampangan woman!

The selection of the first female (and second youngest) Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in the person of Maria Lourdes Sereno by Pres. Benigno Aquino Jr. underscores the great strides women have made in their chosen fields, breaking barriers and rewriting history in the process. Her acclamation as the chief magistrate of the country recalls the gender-transcending achievements of the Kapampangan woman, who have always played important roles in the local society, empowered and privileged like no other.

Long before the terms “equal rights” became battlecries of feminists, the daughters of Pampanga were already enjoying certain perks with regards to land ownership. Like their male counterparts, women inherited land from their parents which they could buy and sell should they chose to. They could retain the land even upon marriage and could bequeath these property to their children, independent of their husbands.

Indeed, even in a society where patriarchs seem to dominate, women were vice-husbands, taking on the head of the family role if the father was absent. Women shared responsibilities with their men, be it in the household or out in the farmlands, swamps and fishponds. Described by priest-historian Fray Gaspar de San Agustin as being “very brave and strong”—both masculine properties, Kapampangan women certainly were as capable as the opposite sex in the execution of their duties.

When new settlements and towns were being established, the Kapampangan women stood by her man. Mabalacat, which started as a forest clearing, may have been founded by the Negrito chief Garagan, but it was his wife, Laureana Tolentino, who became the town cabeza, the first known female head of a Pampanga municipality. Dña. Rosalia de Jesus is credited in history books as the co-founder of Culiat in 1796, the future city of Angeles, alongside her husband, Don Angel Pantaleon de Miranda. Similarly, Botolan in Zambales owes its existence to a woman, known only by the name Dña. Teresa of Mabalacat, who secured a permit in Manila to establish the town in 1819.

The earliest Filipino nuns were also Kapampangans, led by the virtuous Martha de San Bernardo, the first india to be accepted by the monastery of Sta. Clara (founded by Bl. Jeronima de la Asuncion in 1621) around 1633. The Recollect siblings, Mother Dionisia and Mother Cecilia Talangpaz are recognized as the second foundresses of a religious congregration in the Philippines. Half-Kapampangans, they trace their ancestry to the Pamintuans and Mallaris of Macabebe.

Meanwhile, the first female religious to set up an orphanage came from one of the richest families of Bacolor--Sor Asuncion Ventura. A Daughter of Charity, she used her inheritance to put up the Asilo de San Vicente de Paul in 1885. In the literary field, the first woman author was a Pampangueña from Bacolor, Dña. Luisa Gonzaga de Leon. She translated the Spanish religious work Ejercicio Cotidiano (Daily Devotion) into Kapampangan, which was published posthumously around 1844-45.

During the Philippine Revolution, Kapampangan women came in full force to aid the revolucionarios. Led by Nicolasa Dayrit, Felisa Dayrit, Felisa Hizon, Consolacion Singian, Encarnacion Singian, Marcelina Limjuco and Praxedes Fajardo, members of the Junta Patriotica de San Fernando and La Cruz Roja (Red Cross), they also sewed the flag of the Pampanga Batallion in December 1898. Female financiers of the movement included Teodora Salgado and Matea Rodriguez Sioco.

Nursing was still a new course offered at the Escuela de Enfermas of the Philippine General Hospital when Marcelina Nepomuceno (b. 9 Aug. 1881 to Ysabelo Nepomuceno and Juana Paras) enrolled with one of the earliest batches of students. She is known as the first Kapampangan Florence Nightingale. Sharing this honor is Dra. Francisca Galang, the first female Kapampangan medical doctor.

In agriculture and business, a realm often dominated by male hacenderos, the names of Dñas. Tomasa Centeno vda. De Pamintuan (Angeles), Teodora Salgado vda. De Ullman (San Fernando), Victoria Hizon vda. De Rodriguez (San Fernando), Epifania Alvendia vda. De Guanzon (Floridablanca), Donata Montemayor vda. De Vitug (Lubao) and Antonina Reyes vda. De Samson were held in esteem during the Commonwealth years. Widows all, they carried on the work of their late husbands—as sugar planters and entrepreneurs—with grit, hard work and devotion, to successful results.

In the same period, Women’s Clubs were organized by Pampanga matrons in Angeles, Bacolor and San Fernando, which counted Americans, teachers and army wives as members, for their socio-civic pursuits. Educational opportunities expanded with the establishments of colleges and universities. From the 20s to the 40s, elite families sent their daughters to schools in Europe and America, like Paz Pamintuan (daughter of Don Florentino Pamintuan) who finished her M.D. at the Woman’s Medical College in Philadelphia in 1925. Society girl Paquita Villareal was schooled in Hongkong and Germany, while Florencia Salgado went to Paris for her Arts degree. Today, some of the pillars of education are Kapampangan women—like Dr. Barbara Yap-Angeles, founder of Angeles University Foundation in 1962.

In 1976, a Kapampangan woman--Juanita Lumanlan Nepomuceno--broke new ground by becoming Pampanga's first female governor, a position that Lilia Pineda would win 34 years later. Lest we forget, two Kapampangan women have occupied the highest position of the land as Presidents of the Philippines: Corazon Cojuangco-Aquino of Tarlac (1986-1992) and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo of Lubao (2001-2004, re-elected 2004-2010).

All these accomplished names are proof positive that if you want the best man for the job, pick a woman. Better yet, pick a Kapampangan woman!

Monday, September 10, 2012

*309. Star for All Seasons: VILMA SANTOS of Bamban, Tarlac

D'SENSATIONAL ATE VI. Rosa Vilma Santos, teen sensation of the 70s, now the governor of Batangas. Her father, Amado Santos hails from Bamban, Tarlac.

My first brush with a superstar was in 1974, when I came face to face with THE Vilma Santos, who, alongside Nora Aunor, was one of the most popular teen actors of Philippine cinema. That time, she was at the top of her game both as a solo actress and the other half of the Vi and Bobot love team , a sure box-office draw of TV, Movie, Radio and even Advertising.

She had come to Mabalacat to film the war movie, “Mga Tigre ng Sierra Cruz”and several key scenes were to be filmed in my granduncle’s old house in Sta. Ines, conveniently right next to ours. That meant instant access to the production, as we were the designated caretakers of the Morales mansion. The enviable task of fetching Vilma from an undisclosed hotel to be brought to the house was assigned to my father. To get to the shooting venue without attracting the attention of the motley crowd to get a glimpse of the stars, Vilma was whisked off to our own house which had a connecting passage to my relatives’place.

For the next three days, I fell under the spell of Ate Vi—easily transforming me from a Noranian to Vilmanian. More so when, during a lull moment in the shoot, I had the gumption to talk to her (her co-star Dante Rivero refused to be interviewed!), and I even managed to put on tape our short conversation which began with her greeting ”To all the people of Mabalacat, I love you all!!”. Who wouldn’t be charmed by her sweetness? (Though I bet that was a standard line she said to ALL the people in ALL the towns she visited).

Rosa Vilma Tuazon Santos was the second to the eldest child of Amado Santos and Milagros Tuazon, born in Trozo, Tondo on 3 November 1953. The Santoses were a close-knit family from Bamban, Tarlac and Amado’s father was a well-known town physician. Vilma’s father moonlit as a bit player in movies, while an uncle, Amaury Agra, worked as a camera man at Sampaguita Pictures. It was he who tipped off the Santoses about an audition for a child to play the lead in a planned movie, entitled ”Anak, Ang Iyong Ina” in 1963.

The Santoses entered their precocious daughter in the casting call. However, Vilma mistakenly joined a line of children who were auditioning for the movie “Trudis Liit”. She found herself winning the plum role of the Trudis, the maltreated child who cried her way into the hearts of movie fans and box office stardom. Vilma was only 10. That same year, she won her first FAMAS as Best Child Actress of 1963.

As a child superstar, she made more than 27 movies spanning the years 1963-69. Together with Roderick Paulate, Vilma even made a Hollywood war movie—“The Longest Hundred Miles”—which starred Doug Maclure, Ricardo Montalban and Acacdemy Award winner, Katharine Ross. But more was in store for Vilma when she reached her teen-age years.