WHO'S MINDING THE MUNICIPIO? Angeles officials in front of the historic town hall which has now been converted into a museum. Dated 13 Dec. 1956.

WHO'S MINDING THE MUNICIPIO? Angeles officials in front of the historic town hall which has now been converted into a museum. Dated 13 Dec. 1956.The land prospered under their guidance, and in 1810, the couple built a Santuario for the celebration of a Holy Mass. A chaplain, P. Juan Zablan of Minalin, was appointed by church authorities in 1812, but the administration still depended on San Fernando. Culiat progressed as its population increased, and the founding couple thus sought to establish a town detached from San Fernando. Their efforts bore fruit on 8 December 1829 with the official recognition of Culiat as a new town of Pampanga.

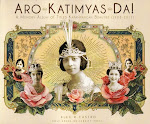

A new name was bestowed upon the town—Angeles—in honor of the Los Angeles Custodios, protectors of the patroness, our Lady of the Most Holy Rosary. But the name also pays tribute to the founder, Don Angel, a former gobernadorcillo, now the acknowledged father of a new town. Ciriaco succeeded his father, serving as the 1st ever gobernadorcillo in 1830.

There was no stopping the growth of Angeles thereafter. A more spacious church replaced the old Santuario in 1833, and in the same year, the Casa Tribunal was erected. The town’s territorial boundaries—which initially included the barrios of Sto. Rosario, San Jose, Amsic, Santol, Cutcut and Pampang—expanded to include 7 barrios of San Fernando: Cacutud, Capaya, Mining, Pandan, Pulungbulu, Sapa Libutad and Tabun. Three barrios were ceded by Mabalacat to Angeles: Balibago, Malabañas and Pulung Maragul. Mexico gave up Cutud. Population increase necessitated the creation of more barrios: Sto Domingo, Anunas, Sto. Cristo and San Nicolas. With the relocation of the market, Tacondo, Sapangbato and Talimunduc started to be populated.

During the Philippine Revolution, Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo transferred the seat of government to Angeles, and it was here that the 1st anniversary of the Philippine independence was celebrated. The town fell to the American forces on 5 November 1899, after a drawn-out battle. The U.S. Army set up their post in Talimundoc, but relocated to Sapang Bato, a place that had better sawgrass for their horses. This expansive place would later be transformed into Fort Stotsenburg, and later, Clark Air Base in 1908.

During the 2nd World War, Stosenburg was carpet-bombed, totally destroying America’s air might. Angeles fell to the Japanese on New Year’s Day in 1942, and Angeleños were witnesses to the Death March of over 50,000 prisoners who passed their town. The liberation of the Philippines signaled a new ear to Angeles, rising from the ashes of the war to become Central Luzon’s premiere city on 1 January 1964, under Republic Act No. 3700.

From thereon, Angeles grew at an exponential rate, thanks in part to the presence of Clark Air Base which provided employment to many Kapampangans, but also spawned businesses of every conceivable variety to cater to the needs of thousands of Americans living in the city. Foremost among this was the entertainment industry, and for years, Angeles was associated with honky-tonk bars, prostitution dens, strip clubs and sleazy joints, and this image as a sort of a wild cowboy town persisted till the '90s.

But in 1991, the Senate vetoed the extension of U.S. military presence in the Philippines, but it was the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo that hastened the closure of Clark. Two years after the cataclysmic disaster, Clark re-emerged as a special economic zone, and once again, Angeleños worked hard to put the city back on its feet and its progress back on track.

Present-day Angeles, with its 33 barangays, lives up to its name as a premiere city-- home to many burgeoning industries and export businesses like furniture, metal crafts, houseware, garments and handicrafts. The Clark Freeport Zone is the site of the city’s emerging technology industry, with multinational call-centers establishing their bases here. An international airport now serves as a major transport hub for the country. Spanking modern malls, commercial infrastructures and efficient expressways now dot the Angeles landscape, and a cultural renaissance is happening right in the heart of the city. Which leads many an Angeleño to believe-- that the holy guardians of their beloved city never sleep.