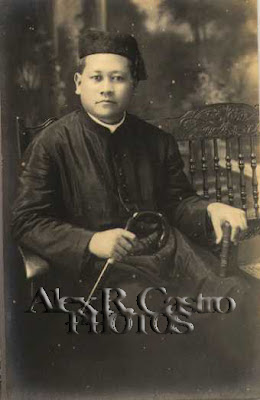

FR. SANTIAGO BLANCO, the last Spanish Augustinian priest of Pampanga, as a young priest. He was sent to Pampanga upon his ordination in 1928 and stayed on, long after the Order let go of its parishes. H dies in Bamban in 1993. Courtesy of Monsgr. Gene Reyes.

No other missionaries had more impact in the creation and development of provinces than the Augustinian frailes that first arrived with Miguel Lopez de Legazpi tour islands in 1565. Just 9 years later, 1575, the Provincia del Santissimo Nombre de Jesus

de Filipinas was already in place to manage effectively the affairs of the missionaries in their pastoral turfs.

To their credit, the Augutinians founded 250 parishes—the most by any order, and 22 of these were in Pampanga.

Some of these missions include Lubao (1572, founded by Fray Juan Gallegos), Betis (1572, Fray Fernando Pinto), Mexico (1581, with Fr. Bernardino de Quevedo

and Fr. Pedro de Abuyoas as the first priests), Guagua (1590, Fray Bernardo de Quevedo), Candaba (1575, Fray Manrique) and Macabebe (1575, Fray Sebastian Molina).

The product of their missionary zeal resulted in many achievements that contributed to the advancements of Pampanga towns. Great builders all, they designed and constructed some of the most beautiful churches in the country—Betis and its baroque decorations, Mexico and its cimborio, Bacolor—said to be the most beautiful in the province, and Lubao, the biggest of all Pampanga churches.

From building grand churches, the Augustinians also founded th schools or escuelas—parochial centers of learning—in Bacolor, Betis, Lubao (Estudio Gramatica later Colegio de Lubao, 1596) and Candaba (Estudio Gramatica, 1596). They also became the first mentors of students, as they became more adept at the local language.

It was the Order that put up the first Augustinian printing press in the country that published pioneering printed materials—from grammar books, dictionaries and novenas. Augustinian friars like Bacolor founder Fray Diego Ochoa, authored the first Arte, Vocabulario y Confesionario en Pampango while Macabebe’s Fray Tallada wrote the first published Kapampangan book--Vida de San Nicolas de Tolentino (1614).

Among the Augustinians were erudites like Fray Guillermo Masnou, who made a study and an inventory of the herbal plants in Pampanga. Fray Antonio Llanos was taken by Mount Arayat’s curious shape, its flora and fauna, and the rivers that flowed from its core, inspiring him to study Pampanga’s mythical mountain.

As a result of their effective evangelical labors, the Augustinians were allowed some autonomy by the Vatican, with little interference from the diocesan bishops in the supervision of the fledgling churches and the administration of the sacraments. Pampanga thus became a showcase of the Augustinians’ missionary work all throughout the Spanish colonial period and beyond.

The parishes of Lubao, Betis, Sasmuan, Porac, Minalin and Sto. Tomas continued to be administered by the Augustinians well into the first half of the 1900s; the last town to go was Floridablanca, whose last Spanish parish priest was Fray Lucino Valles, founder of the St. Augustine Academy in 1951. Other chose to stay here permanently long after their order's duties were over.

Such was the case of Fr. Santiago Blanco, a true blue Spaniard, fondly called Apung Tiago by his Kapampangan constituents. Ordained in 1928, Fr. Blanco was assigned to various towns in Pampanga, including SantoTomas, Betis and Porac. He was responsible for the repainting of the church interiors of Betis during his 1939-49 term.

His next assignment was Porac where he served as parish priest and Spiritual Director from 1950-1959.

When the Augustinians let go of their last remaining parish in Pampanga, Fr. Blanco requested to be left behind. In 1963, his application to become a secular priest was granted by the Holy See. Fr. Blanco moved to the newly created Diocese of Tarlac and became an honorary Monsignor and an Episcopal Vicar.

Fr.Blanco took residence in Bamban until his passing in 1993, his lifeworks in Pampanga a testament to the unflagging Augustinian missionary heart and spirit.

Showing posts with label Betis. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Betis. Show all posts

Tuesday, November 24, 2015

Monday, February 10, 2014

*362. MUSICUS: The Sound of Our Fiestas!

MAJOR, MAJOR, MAJORETTES. Lovely Kapampangan majorettes pose for a shot before joining the local 'musicus' in their rounds around the town, lending a festive air to Pampanga fiestas. ca. 1950s.

It’s our Mabalacat city fiesta as I write this article---and it’s a pity that I am not there to enjoy the festivities, not to mention the colorful sights, smells and sounds that accompany the yearly February 2 proceedings. You just know it’s fiesta season when blue and white buntings start lining the streets and tiangge stalls begin popping up along the church perimeter, offering all sorts of goods, from the useful to the bizarre.

But nothing says “fiesta” more than the presence of music-making bands—“musicus”—staples of every fiesta, in every town and barrio of the Philippines. With their gleaming brass horns, cymbals, lyres, trumpets, drums and bugles, uniformed band members--preceded by a bevy of pretty, baton-twirling majorettes—are always a striking sight when they take to the streets, making stirring melodies as they march, with a bit of choreography on the side.

Evolved from the roving “musikung bumbung” (bamboo bands), today’s bands drew early inspirations from the acclaim gained by the Philippine Scouts Band at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. The band was the largest at the fair, and it had a large repertoire of 80 pieces, against Fredric Sousa’s 65. “They were good and had temperament which the other bands lacked”, wrote one visitor.

Needless to say, they took the world’s fair by storm, often performing in drills with “Little Macs”—young Macabebe veterans who enlisted for service to fight for the Americans in the Philippine-American War. Certainly, the incredible feat of that Philippine band helped fuel interest back in the islands for organized bands.

Just 4 years after that U.S. triumph, the Philippines had its own national fair—the Manila Carnival—and in 1909, the band from Angeles outplayed its rivals to clinch first place in the musical band competition. It was during town fiestas, however, that local bands gave rein to their musical creativity.

In the Betis fiesta of 1959, a local band—Banda 46—was tasked to march around the town starting on the fiesta eve, from 3 a.m. to 5 a.m.— to rouse people from their sleep—for a period of nine days! The day was capped with musical duel between bands---Serenata ning Musicus—in which Banda Sexmoan 12 played against Banda Sexmoan 31 at the church patio in a test of musical endurance and bravado.

On 29 December, an exhibition was staged by a bevy of band majorettes, displaying their dancing and baton-twirling skills while band members in their gala uniforms played their best. On the fiesta day itself, 12 bands paraded along the streets, with some, invited from different provinces: Banda Baliwag, Banda Cabiao 96, Banda San Leonardo, Banda Bocaue, Banda Sexmoan 31, Banda Sexmoan 12, Banda Pulilan, Banda Candaba, Banda Duat Bacolor, Banda San Antonio Bacolor, Banda 48 Betis, Banda 26 Betis and the 600 Clark Field Air Force Band thru the courtesy of Mr. Salvador Pangilinan.

The bands then converged to escort the carrozas of the town patrons for the grand procession. The 1939 Lubao town fiesta from 4-5 May, was also made exciting with the presence of 3 “musicus”: Banda Lubao, Banda Sinfonica (Malabon) and Banda Buenaventura (Baliwag). The 3 bands were gathered at the municipio before they set out for the Poblacion, treating Lubeños to a musical extravaganza never before seen in the town.

A 1946 fiesta souvenir program from Sta. Rita detailed also the arrival of 3 bands that played on the eve of the fiesta, the first one held after the Liberation: Banda Sta. Rita, Banda 31 from Sexmoan and Banda San Basilio. The next day, May 22, they gave it their all at the Serenata ding Banda de Musica. Even a small barrio could very well afford to pay a local “musicus” to lend gaiety to its fiesta.

In 1957, Valdes, a barrio of mostly agricultural families in Floridablanca, had two bands performing for their May 19 fiesta: the popular Banda 31 of Sexmoan which delighted residents in Gasac and Talang, and Banda Juan dela Cruz which came all the way from Cabiao, Nueva Ecija, to play at Looban and Mabical. On May 18, Saturday, a free concert was mounted featuring the two bands, highlighted by a military drill.

I just can’t imagine a fiesta without a “musicus”. Bands just don’t set the stage and the mood for a celebration. But long after the food, the drinks, the rides, the sideshows and the baratilyos are gone, it is the voice of the band that will live on—inspiring, rousing, uplifting airs, that may as well be the theme music of our joyous lives!

Labels:

Angeles,

Betis,

Floridablanca,

Kapampangan music,

Lubao,

Mabalacat,

Pampanga,

Sasmuan,

Sta. Rita

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

*307. OF TREES, TOWNS AND TOPONYMS

BUT ONLY GOD CAN MAKE A TREE. A whole forest of balakat trees shade a camping site at sitio Mascup, a favorite resort of domestic tourists in Mabalacat, Pampanga. The tall, hardwood tree gave the town its name. Ca. 1920s.

The names of Pampanga towns are among the most unique in the Philippines—and leading in intrigue and mystery would be, to my mind, Mexico and Sexmoan. Mexico’s name, for instance, has always been a source of puzzlement for toponymists—researchers who study of place-names. One fanciful version has it that Mexicans (Guachinangos of Northern America) actually lived in the town and gave it its name. More controversial is the name of Sexmoan, which has, though the years elicited gasps of disbelief from visitors, due to its seeming sexual overtones.

No wonder, the town has reverted back to the local version of its name—“Sasmuan”—a meeting place—as it was known to be an assembly point for people around the area whenever Chinese insurgents threaten to overrun the region. Of course, there were other ways of naming towns, and the more common would be to name them based on their distinct geographical and natural features, including flora and fauna typical of the place. It was in this manner that many towns in Pampanga got their names.

Apalit, for instance, got its name from the first class timber called ”apalit” or narra (Pterocarpus indicus Willd.) that grew profusely along the banks of Pampanga River. Betis was named similarly—after a vary large timber tree called “betis”(Bassia betis Merr.) that grew on the very site where the church was constructed. It was said that this particular tree was so tall that it cast its shadow upon Guagua town every morning. Another border town, Mabalacat, derived its name from the abundance of “balakat” trees (Zizyphus talanai Blanco) that grew around the area. The balakat tree is known for its straight and sturdy hardwood trunk that were used as masts for boats and ships of old.

The riverine town of Masantol owes its name to the santol tree (Sandoricum koetjape Merr.) , a third class timber tree. It may be that the place had an abundance of these popular fruit-bearing trees but another story had it that local fishermen bartered part of their catch with the tangy santol fruits carried by Guagua merchants that plied the waters of the town. Santol was the favourite souring ingredient of the locals in the cooking of “sinigang”, and soon, the town was overrun by santol fruits.

A tall rattan plant gave Porac its name, as we know it today. The red Calamus Curag can grow up to 8 feet and is known locally as “Kurag” or “Purag”, later corrupted to Porac. Nearby Angeles City was once known as Culiat (Gnetum indicum Lour. Merr.) , a woody vine with leathery leaves that once grew wild in the vicinity. Not only while towns, but countless barrios and barangays were named after trees, shrubs, hardwoods, plants and vines—Madapdap, Balibago, Cuayan, Pulungbulu, Mabiga, Sampaloc, Baliti, Bulaon, Dau, Lara, Biabas, Alasas, Saguin, Camatchiles, to name just a few.

Some of the trees that grew so thickly in different parts of our province are now a rare sight, with some considered as bound for extinction. For many years, the only balakat tree that could be seen in Mabalacat, were two or three trees planted in the perimeter of the Mabalacat church. Culiat is listed as an endangered plant and a few examples could be found in Palawan and in U.P. Los Baños, Laguna. Sometime in 2003, Holy Angel University in Angeles City made an effort to collect plants and trees that gave their names to Pampanga towns and barrios. Today, these can be seen growing in lush profusion around the school atrium. By saving these trees, we also save histories of towns for the next generation to learn, to value and to appreciate.

The names of Pampanga towns are among the most unique in the Philippines—and leading in intrigue and mystery would be, to my mind, Mexico and Sexmoan. Mexico’s name, for instance, has always been a source of puzzlement for toponymists—researchers who study of place-names. One fanciful version has it that Mexicans (Guachinangos of Northern America) actually lived in the town and gave it its name. More controversial is the name of Sexmoan, which has, though the years elicited gasps of disbelief from visitors, due to its seeming sexual overtones.

No wonder, the town has reverted back to the local version of its name—“Sasmuan”—a meeting place—as it was known to be an assembly point for people around the area whenever Chinese insurgents threaten to overrun the region. Of course, there were other ways of naming towns, and the more common would be to name them based on their distinct geographical and natural features, including flora and fauna typical of the place. It was in this manner that many towns in Pampanga got their names.

Apalit, for instance, got its name from the first class timber called ”apalit” or narra (Pterocarpus indicus Willd.) that grew profusely along the banks of Pampanga River. Betis was named similarly—after a vary large timber tree called “betis”(Bassia betis Merr.) that grew on the very site where the church was constructed. It was said that this particular tree was so tall that it cast its shadow upon Guagua town every morning. Another border town, Mabalacat, derived its name from the abundance of “balakat” trees (Zizyphus talanai Blanco) that grew around the area. The balakat tree is known for its straight and sturdy hardwood trunk that were used as masts for boats and ships of old.

The riverine town of Masantol owes its name to the santol tree (Sandoricum koetjape Merr.) , a third class timber tree. It may be that the place had an abundance of these popular fruit-bearing trees but another story had it that local fishermen bartered part of their catch with the tangy santol fruits carried by Guagua merchants that plied the waters of the town. Santol was the favourite souring ingredient of the locals in the cooking of “sinigang”, and soon, the town was overrun by santol fruits.

A tall rattan plant gave Porac its name, as we know it today. The red Calamus Curag can grow up to 8 feet and is known locally as “Kurag” or “Purag”, later corrupted to Porac. Nearby Angeles City was once known as Culiat (Gnetum indicum Lour. Merr.) , a woody vine with leathery leaves that once grew wild in the vicinity. Not only while towns, but countless barrios and barangays were named after trees, shrubs, hardwoods, plants and vines—Madapdap, Balibago, Cuayan, Pulungbulu, Mabiga, Sampaloc, Baliti, Bulaon, Dau, Lara, Biabas, Alasas, Saguin, Camatchiles, to name just a few.

Some of the trees that grew so thickly in different parts of our province are now a rare sight, with some considered as bound for extinction. For many years, the only balakat tree that could be seen in Mabalacat, were two or three trees planted in the perimeter of the Mabalacat church. Culiat is listed as an endangered plant and a few examples could be found in Palawan and in U.P. Los Baños, Laguna. Sometime in 2003, Holy Angel University in Angeles City made an effort to collect plants and trees that gave their names to Pampanga towns and barrios. Today, these can be seen growing in lush profusion around the school atrium. By saving these trees, we also save histories of towns for the next generation to learn, to value and to appreciate.

Monday, April 2, 2012

*288. The Seminary Years of REV. FR. TEODORO S. TANTENGCO

THE CHOSEN. Teodoro Tantengco of Angeles was one of 12 seminarians who started their priestly studies at the San Carlos Seminary beginning in 1908. Eight years later, he was ordained as a priest. He was the long-time cura parocco of San Simon.

THE CHOSEN. Teodoro Tantengco of Angeles was one of 12 seminarians who started their priestly studies at the San Carlos Seminary beginning in 1908. Eight years later, he was ordained as a priest. He was the long-time cura parocco of San Simon. In 1908, twelve new seminarians entered the august halls of the Conciliar San Carlos, the first diocesan seminary founded in the Philippines. That time, the seminary was located along Arzobispo Street in Intramuros, beside the new San Ignacio Church. Three years earlier, the American Archbishop Jeremiah Harty had turned over the administration of the premiere seminary in the country to the Jesuits.

Of the 12 seminaristas, two were full-blooded Kapampangans and both from the town of Angeles—Felipe de Guzman and Teodoro Tantengco y Sanchez. Teodoro had entered just two months ahead of Felipe, on 1 July 1908. San Carlos had quite a substantial number of Kapampangan seminaristas enrolled even in those years, coming fromsuch towns as Betis (Victoriano Basco, Mariano Sunglao, Alberto Roque, Mateo Vitug); Sta. Rita (Anacleto David, Pablo Camilo, Eusebio Guanlao, Mariano Trifon Carlos, Prudencio David); Macabebe (Brigido Panlilio, Atanacio Hernandez, Maximo Manuguid, Pedro Jaime); Bacolor (Rodolfo Fajardo, Tomas Dimacali, Vicente Neri); Porac (Mariano Santos); Angeles (Pablo Tablante); Guagua (Laureano de los Reyes) and Candaba (Lucas de Ocampo).

Seminary life was conducted under the watchful eye of the Rector, Fr. Pio Pi and the Minister, Fr. Mariano Juan. Teodoro and his classmates were drilled in Liturgy, Music, English and Ascetics. Moral Theology and Philosophy were taught at santo Tomas while other courses like Math, Greek, French and even Gregorian Chants were also offered. Discipline was exact; some form of corporal punishment were meted out for acts of disobedience—like being put on silence and making public retractions of some kind.

Out of the classrooms, the Carlistas were employed in the Cathedral services and liturgical events, like in the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Pius X as a priest. The seminaristas assisted in the altar services at the mass officiated at the Manila Cathedral. Similarly, the class were mobilized to attend to Archbishop Michael Kelly from Sydney, Australia who had come to Manila for a short visit.

In 1909, Teodoro was present at the consecration of Bishop Dennis Dougherty’s successor, Bishop Carroll, as the Bishop of Vigan. The class also performed preaching duties at the Bilibid Prison and at the San Lazaro Hospital, where the Carlistas ministered to the needs of the patients.

There was no rest during their vacation as Teodoro took classes in Latin, English and Tagalog, even as the superiors organized trips to Sta. Rita, Angeles, Dolores, Porac and Guagua. There were all-day picnics and excursions in Cainta, Cavite, Malabon, San Pedro Makati, Sta. Ana and at the hacienda of a certain Captain Narciso in Orani. Regular “dias de campo” were scheduled in Pasay and Malabon, where the youths swam, played with their bands and refreshed themselves with tuba, melons and ‘agua fresca’.

On 10 April 1910, the Carlistas took part in a historic church event which saw the establishment of four dioceses by Pius X—Calbayog, Lipa, Tuguegarao and Zamboanga. The seminarians were in full attendance to mark this important occasion for the Philippine church. The next year, the seminaristas were allowed to attend the Manila Carnival from Feb. 21-28 at Luneta, where they thrilled to the sight of the aerial acrobatics performed by American pilot Mars.

Teodoro and his classmates were taken by surprise on 17 August 1911, when they received orders from Archbishop Harty to transfer all San Carlos seminarians to the Seminario de San Francisco Javier (the old Colegio de San Jose) located along Padre Faura St. Teodoro was one of 30 seminarians who moved to San Javier, a merger-transfer that would last for 2 years, until the seminary closed in 1913.

With the termination of the Jesuit administration, the seminarians made their final move to a refurbished building in Mandaluyong, which was constructed by Augustinians in 1716 and abandoned in 1900. The Vincentian fathers (Congregation of the Mission) took over the management of the new site of Seminario de San Carlos.

It was here that Teodoro Tantengco, finished his priestly studies which culminated in his ordination in 1916. He was assigned immediately back to his home province in Pampanga, first as assistant priest of Masantol, then as the cura parocco of San Simon which he served for many fruitful years. In 1947, he was in Tayuman, Sta. Cruz.

The accomplished and well-loved priest passed away in San Fernando in 1954. A nephew, Betis-born Teodulfo Tantengco followed in his footsteps, enrolling in his uncle’s alma mater and, after ordination, served various parishes like Arayat and Dau, Mabalacat, Pampanga until his death in 1999.

There was no rest during their vacation as Teodoro took classes in Latin, English and Tagalog, even as the superiors organized trips to Sta. Rita, Angeles, Dolores, Porac and Guagua. There were all-day picnics and excursions in Cainta, Cavite, Malabon, San Pedro Makati, Sta. Ana and at the hacienda of a certain Captain Narciso in Orani. Regular “dias de campo” were scheduled in Pasay and Malabon, where the youths swam, played with their bands and refreshed themselves with tuba, melons and ‘agua fresca’.

On 10 April 1910, the Carlistas took part in a historic church event which saw the establishment of four dioceses by Pius X—Calbayog, Lipa, Tuguegarao and Zamboanga. The seminarians were in full attendance to mark this important occasion for the Philippine church. The next year, the seminaristas were allowed to attend the Manila Carnival from Feb. 21-28 at Luneta, where they thrilled to the sight of the aerial acrobatics performed by American pilot Mars.

Teodoro and his classmates were taken by surprise on 17 August 1911, when they received orders from Archbishop Harty to transfer all San Carlos seminarians to the Seminario de San Francisco Javier (the old Colegio de San Jose) located along Padre Faura St. Teodoro was one of 30 seminarians who moved to San Javier, a merger-transfer that would last for 2 years, until the seminary closed in 1913.

With the termination of the Jesuit administration, the seminarians made their final move to a refurbished building in Mandaluyong, which was constructed by Augustinians in 1716 and abandoned in 1900. The Vincentian fathers (Congregation of the Mission) took over the management of the new site of Seminario de San Carlos.

It was here that Teodoro Tantengco, finished his priestly studies which culminated in his ordination in 1916. He was assigned immediately back to his home province in Pampanga, first as assistant priest of Masantol, then as the cura parocco of San Simon which he served for many fruitful years. In 1947, he was in Tayuman, Sta. Cruz.

The accomplished and well-loved priest passed away in San Fernando in 1954. A nephew, Betis-born Teodulfo Tantengco followed in his footsteps, enrolling in his uncle’s alma mater and, after ordination, served various parishes like Arayat and Dau, Mabalacat, Pampanga until his death in 1999.

Labels:

Angeles,

Bacolor,

Betis,

Candaba,

Guagua,

Pampanga,

Pampanga missionaries,

Philippines,

Sta. Rita

Sunday, February 26, 2012

*283. DR. MIGUEL P. MORALES, Mabalacat's 1st Post-War Mayor

THE MORALES MAYORALTY. Dr. Miguel Pantig Morales, first elected mayor of post-war Mabalacat, comes from a long line of politicos who served the town in different capacities, a tradition now being continued by grandson, Marino, current mayor of this first class municpality. Ca. 1933.

THE MORALES MAYORALTY. Dr. Miguel Pantig Morales, first elected mayor of post-war Mabalacat, comes from a long line of politicos who served the town in different capacities, a tradition now being continued by grandson, Marino, current mayor of this first class municpality. Ca. 1933.The Moraleses are well-known in Mabalacat as a long-standing political clan of the town, a tradition that was started by Quentin Tuazon Morales (b. 1856/d.1928) who became a teniente mayor of barangay Poblacion in the late 19th century. When he moved his family to Sta. Ines, he became a cabeza of that barrio. His youngest son with Paula Cosme Guzman, Atty. Rafael Morales, also was elected as consejal (councilor) in the 1930s.

Feliciano Morales, Quentin’s brother, was also a cabeza of barangay Quitanguil. But it would be his son with Juana Pantig--Dr. Miguel Morales--who would solidify the Moraleses’ reputation as a family of politicos, by being elected as the first mayor of Mabalacat, after the Liberation.

Born on 23 September 1893, Miguel was educated in Mabalacat under Maestro Bartolome Tablante and in Angeles under Maestro Pedro Manankil. For his higher education, he was sent to the Liceo de Manila and Colegio de Ntra. Señora del Rosario. While still a student, Miguel gave vent to his literary pursuits, with many of his prose and poems seeing print on “E Mañgabiran”, a widely circulated newspaper. He wrote under the pen name “M. L. Amores”. Miguel was also an active member of the social club, “Sibul ning Lugud”, which he served as Vice President.

His main ambition though was to pursue a career in medicine, and so in 1915, Miguel enrolled at the University of Santo Tomas for his medical degree which he finished in 1920. After his residency at the San Juan de Dios Hospital, he took the board exams and passed with flying colors.

The young doctor then went back home to Mabalacat to practice his profession and became an established medico-cirujano. During this time, he married his first wife, Jovita Gabriel of Betis, with whom he had five children. A second marriage to Felicidad Carlos would result in three more children.

In 1933, Dr. Morales was appointed as a Medico de Sanidad (head of the health department) of Apalit. He settled his family in Mawaque during the war years but kept his Apalit office. Though times were difficult, he offered his medical services for free, gave food to victims of the war and aided the Americans who participated in the infamous Death March. In 1945, he was finally transferred back to Mabalacat.

A grateful town elected him as its mayor in 1948, the first post-war town head so chosen by local ballot. As mayor, he was responsible for building the wooden Morales Bridge, which provided the vital link between Sta. Ines and Poblacion. Mayor Morales also organized the first hydroelectric power plant, later operated by the Tiglaos. He was at the forefront of a campaign against the rising Huk movement when he was assassinated in 1951.

Today, the Morales name lives on in the political scene with the term of Mayor Marino Morales, his grandson. For two decades now, Mayor Boking, as he is called, has been the chief executive of Mabalacat, the longest serving mayor in the Philippines. By a twist of luck and technicalities, he survived the electoral protests of chief rival Anthony Dee and the challenge posed by his estranged daughter Marjorie Morales-Sambo who ran—and lost—against him in the last election. The elevation of this first class municipality into a city will give Mayor Morales another chance to extend his term as the first city mayor of Mabalacat—that is, if his winning streak continues.

Sunday, February 5, 2012

*280. His First Mass: FR. VICENTE MALIG CORONEL

FATHER ALMIGHTY. New priest Fr. Vicente Malig Coronel of Betis, finished his priestly studies at San Carlos Seminary and went on to become a familiar figure in Pampanga's religious scene.

FATHER ALMIGHTY. New priest Fr. Vicente Malig Coronel of Betis, finished his priestly studies at San Carlos Seminary and went on to become a familiar figure in Pampanga's religious scene. A new priest’s sacerdotal ordination is always a joyous and memorable occasion, a culmination of his seminary studies necessary to fulfill his holy calling. But his first thanksgiving mass takes on an even extraordinary significance for it marks his assumption of a new role--that of God’s chosen apostle-- anointed to preach and spread the good news of His Salvation.

On Easter Monday, 19 April 1954, Fr. Vicente Malig Coronel had the privilege of celebrating his first Solemn High Mass of Thanksgiving, and we have his souvenir card to remember that special day in the young priest’s life.

Betis-born Vicente, was one of the children of Gaudencio David Coronel, which also included Rodolfo, Gerardo, Santos and Dominga . His vocation was shaped early by his family and town, which prides itself in having produced the most number of priests than any other Pampanga town. He went to pursue his studies at the San Carlos Seminary, which had quite a sizable number of Kapampangan seminarians who even organized themselves into the Academiang Pampangueña.

On that fateful day at the same church where he served as an altar boy--the Church of Santiago Apostol of Betis, the neo-presbyter celebrated his own Mass at exactly 8:00 in the morning. Fr. Coronel was assisted by Rt. Rev. Msgr. Cosme P. Bituin who would, in the same year, be his superior in Angeles. Serving as Deacon and Subdeacon respectively were Neo-Pbtr. Severino G. Casas and Alejandro O. Ocampo. The assigned Preacher was the Very Rev. Santiago G. Guanlao. In charge with the Thurifer was Minorist Jose C. Guiao. Seminarians from U.S.T. served as Acolytes while the Torchbearers were his schoolmates from San Carlos Seminary. The Mater Boni Consilii Choir provided the music while Very Rev. Fidel M. Dabu hosted the ceremonies.

The sponsors of Fr. Coronel at this Mass were Msgr. Cosme Bituin, Sir Knight German R. Songco and Dña. Carmen Coronel Pecson. Immediately after the Mass, a fraternal reunion was held at the Coronel family residence.

After his ordination, Fr. Coronel was assigned as the Assistant Parish Priest, of Angeles in 1954. Together with Frs. Alfredo Lorenzo and Maximino Manuguid, Fr. Malig helped Msgr. Cosme P. Bituin run the affairs of the Sto. Rosario Church, proving his dedication in serving Angeleños for many years. One highlight of his religious career was his special audience and blessing of His Holiness Pope John XXIII on 29 July 1959, at his summer residence in Castel Gandolfo in Rome.

From Angeles, he was assigned in Tarlac and also had a stint at Our Lady of Penafrancia in Manila from 1976-1983, Fr. Coronel passed away on 22 June 1998.

“You have not chosen Me, but I have chosen you”—John 6, 16.

Sunday, December 19, 2010

*228.Teeth for Tat: KAPAMPANGAN CIRUJANO-DENTISTAS

CLOSE-UP CONFIDENCE. Dr. & Mrs. Tomas Yuson (the former Librada Concepcion) on their wedding day in 1936. Dr. Tom Yuson was the leading Kapampangan dentist in his time, and a co-founder of the Pampanga Dental Association in 1930. Personal Collection.

CLOSE-UP CONFIDENCE. Dr. & Mrs. Tomas Yuson (the former Librada Concepcion) on their wedding day in 1936. Dr. Tom Yuson was the leading Kapampangan dentist in his time, and a co-founder of the Pampanga Dental Association in 1930. Personal Collection.Pampanga is renowned for its eminent medical doctors and surgeons of superb skills. The names of Drs. Gregorio Singian, Basilio Valdez, Mario Alimurung and Conrado Dayrit come to mind. The allied course of Dentistry has also given us notable Kapampangans professionals who have made a name for themselves in this less crowded field of dental science, and their achievements are no less significant.

In the first decades of the 20th century, when colleges and universities started offering medical courses, students were drawn more to Medicine and Pharmacy. Dentistry was not even considered a legal profession during the Spanish times--tooth pullers were employed to take care of problem molars, cuspids and bicuspids.

As public health was given emphasis during the American regime, the course of dentistry was given legitmacy with the opening of the Colegio Dental del Liceo de Manila. It would become the Philippine Dental College, the pioneer school of dentistry in the Philipines. Students started enrolling in the course as more schools like the University of the Philippines opened its doors to students. The state university established its own Department of Dentistry that was appended to its College of Medicine and Surgery. The initial offering attracted eight students. That time, with a population of eight million, there was only one dentist to every 57,971 Filipinos. More educational insititutions would follow suit: National University (1925), Manila College of Dentistry (1929) and University of the East(1948. In 3 to 4 years, these schools would be graduating doctors of dental medicine, many of whome were Kapampangans.

One of the more accomplished is Guagua-born Tomas L. Yuzon, born on 7 March 1906, the son of Juan Yuzon and Simona Layug. He attended local schools in Guagua until he was 16, then moved to Philippine Normal School in Manila. At age 20, he enrolled at the country’s foremost dental school, the Philippine Dental College, and finished his 4-year course in 1930. That same year, he passed the board and began a flourishing career as a Dental Surgeon in San Fernando.

In 1930, together with Dr. Claro Ayuyao of Magalang and Dr. H. Luciano David of Angeles, Yuzon founded the Pampanga Dental Association on 25 October 1930. The constitution, rules and by-laws were patterned after the National Dental Association. The initial members of 30 Pampanga dentists aimed to elevate the standard of their profession and foster mutual cooperation and understanding among themselves. Elected President was Dr. Ayuyao, while Dr. Yuzon was named as Secretary. The P.D.A. was the first provincial organization to hold demonstrations in modern dental practice and was an authorized chapter of the national organization.

As a proponent of modern dental medicine, Dr. Yuzon was one of the first to use X-Ray and Transillumination in diagnosing his patients. He was also an active member of the Philippine Society of Stomatologists of Manila. He received much acclaim for his work, and was a respected figure in both his hometown—where he remained a member of good standing of “Maligaya Club”, as well as in his adopted community of San Fernando. On 19 Sept. 1936, he married Librada M. Concepcion of Mabalacat, daughter of Clotilde Morales and Isabelo Concepcion. They settled in San Fernando and raised three children: Peter, Susing and Lourdes.

Guagua seemed to have produced more dentists than any other Pampanga town in the late 20s and 30s and some graduates from the Philippine Dental College include Drs. Marciano L. David (1925), Emilio Tiongco (1931, worked as assistant to dr. F. Mejia), Domingo B. Calma (who was a town teacher before becoming a dental surgeon), Eladio Simpao (1929), Alfredo Nacu (1929) and Hermenegildo L. Lagman (an early 1919 graduate and also a member of the Veterans of the Revolution!)

The list of of Angeleño dentists is headed by Dr. Lauro S. Gomez who graduated at the top of his class at National University in 1930, Mariano P. Pineda (PDC, 1930, a dry goods businessman and a Bureau of Education clerk before becoming a dentist), Pablo del Rosario and Vicente de Guzman.

In Apalit, Dr. Roman Balagtas placed ads that stated “babie yang consulta carin San Vicente Apalit, balang aldo Miercoles". He also had a clinic in Juan Luna, Tondo. Arayat gave us the well-educated and well-travelled Dr. Emeterio D. Peña, who was schooled at the Zaliti Barrio School, Arayat Institute (1916), Pampanga High School (1916-18), Batangas High School (1918-1919) and at the Philippine Dental College (1920-23). He squeezed in some time to study Spanish at Instituto Cervantino (1921-23). Then he went on to practice at San Fernando, La Union, Tayabas, Mindoro, Nueva Ecija and Tarlac. Also from Arayat were Drs. Agapito Abriol Santos and Alejandro Alcala (both PDC 1931 graduates). The latter was famed for his “painless extractions” at his 1702 Azcarraga clinic which ominously faced Funeraria Paz!

Betis and Bacolor are the hometowns of dentists Exequiel Garcia David (who worked in the Bureau of Lands and as a private secretary to Rep. M. Ocampo) and Santiago S. Angeles, respectively. Candaba prides itself in having Dr. Dominador A. Evangelista as one of its proud sons in the dental profession while Lubao has Gregorio M. Fernandez, a 1928 Philippine Dental College graduate, who went on to national fame as a leading film director, and Daniel S. Fausto, who graduated in 1934..

Macabebe doctors of dental medicines include Policarpio Enriquez , a 1931 dentistry graduate of the Educational Institute of the Philippines, Francisco M. Silva PDC, 1923) who also became a top councilor of the town. Magalang gave us the esteemed Dr. Claro D. Ayuyao who became the 1st president of the Pampanga Dental Association and Dr. Alejandro T. David, a product of Philippine Dental College in 1928, who was also a businessman-mason.

Dentists Dominador L. Mallari (PDC, 1932) and Pedro Guevara (UST, Junior Red Cross Dentist 1923-29) came from Masantol. Guevara even went on to become a councilor-elect of his town. The leading dentist from Minalin, Sabas N Pingol (PDC, 1929) announced that: “manulu ya agpang qng bayung paralan caring saquit ding ipan at guilaguid’. He moved residence to Tondo and kept a clinic at 760 Reyna Regente, Binondo.

In Sta. Rita, Drs. Maximo de Castro (PDC, 1931) and Sergio Cruz (PDC, 1932) had private practices in their town. Finally, well-known Fernandino dentists of the peacetime years include Paulino Y. Gopez (UP, College of Dentistry, 1931) and the specialist Dr. Miguel G. Baluyut, (PDC, 1927) who took a course in Oral Surgery at the Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois. Trailblazers of some sorts were lady dentists Paz R. Naval, a dental surgeon, Consuelo L. Asung who held clinics in San Fernando and Mexico.

Next time you flash those pearly whites and gummy smiles, think of the early pioneering Kapampangan dentists who, with their knowledge, talents and skills, helped elevate the stature of their profession, putting it on equal footing with mainstream medicine.

Labels:

Angeles,

Bacolor,

Betis,

Candaba,

Guagua,

Kapampangan personalities,

life blog,

Macabebe,

Magalang,

Masantol,

Minalin,

Pampanga,

Philippines,

San Fernando,

Sta. Rita

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

*217. CARVING A NICHE IN HISTORY

KA-ARTE MO! An advertisement of "El Arte", owned and operated by academically-trained sculptor Maximino J. Jingco of Betis, touts the services of the shop. The artisans made monuments, wooden statues, mrble figures, and many more. Dated 1933.

KA-ARTE MO! An advertisement of "El Arte", owned and operated by academically-trained sculptor Maximino J. Jingco of Betis, touts the services of the shop. The artisans made monuments, wooden statues, mrble figures, and many more. Dated 1933.Sculpture is an art where Kapampangans reign supreme as masters. Paete may have their manlililoks, but their works are often imbued with folk quality, while the carvers of northern highlands limit their carving to ethnic and souvenir art. Kapampangan sculptors on the other hand, are a versatile lot—sculpting everything from religious statuaries, rebultos, furniture, monuments and decoratives.

Many of the early sculptors were untrained and unschooled, most often coming from Betis, regarded as Pampanga’s old carving district. There was a lot of wood in those days, coming from logs that floated on Betis River, cut from the forests of alta Pampanga and the nearby provinces of Bataan and Zambales. The historian Mariano Henson notes: “In the matter of carving images, altars, ornaments, furnitures, the people of Betis during the 17th and 18th centuries, again are mentioned here to be masters in the art of their own time”.

It is no wonder that the 19th century works of Kapampangan sculptors and carvers were kept in Spanish museums. Some of the sculpted pieces featured in a 19th c. Madrid exhibit included a bamboo woodcarving made in Mexico, a pair of polychromed wooden busts of El Mediquillo (Medicine Man) and La Comadrona (The Midwife) from Sta. Rita, and another pair of tipos del pais figurines from the same town.

There was a demand for religious sculptors about this time, and Isabelo Tampinco filled this need. Born in Binondo but descended from Lakandula, Tampinco was the first to popularize the use of Filipiniana motifs like anahaw leaves, banana and bamboo in his carving, known today as estilo Tampinco. Considered as his obra maestra are the decorations he did for the church of San Ignacio, as well as the magnificent image of San Ignacio itself, both destroyed in the last war.

One of his workers was a talented young man from Guagua, Maximiano Jingco. Born on 6 July 1904 to Sabas and Irinea Jingco, Maximino grew up in Manila, finishing his primary schooling in Quiapo in 1914. He finished his secondary course at Manila High School in 1917. Unlike unschooled artisans, Maximino attended the University of the Philippines and enrolled in Sculpting, one of the few Kapampangans to do so (Note: Graduating from U.P. even earlier was Hipolito Lampa of Bacolor, who finished Fine Arts in 1916). In 1926, Maximino finally became a successful “graduado en Bellas Artes”.

Commercial workshops or talyers of sculptors sprouted in Quiapo, mostly catering to the santo trade. Maximino chose to specialize in secular art (non-religious) and, in 1927, he opened his own shop back home in Guagua—“El Arte, Taller de Escultura y Pintura”. A 1933 ad described his shop thus: “Iting taller a iti metung ya caring peca maragul a oficina quieti Capampangan a maliaring tatanggap qng obrang escultura antimo ding macatuqui: Monumentos, Estatuas en Madera, Marmol. Pintura, at aliua pa. (This shop is one of the largest offices in Pampanga which has the capacity to accept commissioned sculptures like the following: Monuments, Statues in wood and marble, Painting and others.) Jingco lived by his motto: “Magluid qñg capanintunan” (Long live livelihood) and his business prospered for many years.

Equally successful was the prodigious Juan Flores (b.1902) of Sta. Ursula, Betis. He started as an apprentice in the shop of Maximo Vicente, and progressed to being a restorer of santos and ecclesiastical arts for Luis Araneta and went on to help build the Betis woodcarving industry. His carvings adorn many churches, palaces and hotels here and abroad. In 1972, he even won a sculpting competition in the United States organized by the University of the California. Back home, he and his Kapampangan team helped refurbish the Malacañang Palace, carving wooden ornamentations and wooden panels for the various rooms, including the three wood and glass chandeliers in the Ceremonial Hall.

Juan Flores passed away in 1995. Happily, his torch has been passed on to contemporary mandudukits who are active to this day: Spanish-trained Willy Layug (an architecture graduate from U.P.), Boyet Flores ( a Flores descendant), Peter Garcia, Salvador Gatus and Nick Lugue of Apalit. In their hands, Kapampangan creativity lives on.

Sunday, September 26, 2010

*215. RECUERDOS DE LA FAMILIA: The Rites of ‘Daun’

SUS DESCONSOLADOS AMIGOS. A crowd of relatives, friends and sympathizers attend the burial rites of a deceased in Candaba, Pampanga. He will once again be remembered on 'daun'. Nov. 1, with visits, floral, prayer and candle offerings from his family. Ca. 1920s.

SUS DESCONSOLADOS AMIGOS. A crowd of relatives, friends and sympathizers attend the burial rites of a deceased in Candaba, Pampanga. He will once again be remembered on 'daun'. Nov. 1, with visits, floral, prayer and candle offerings from his family. Ca. 1920s.The annual trek to the campo santo to honor the dead begins days or even weeks before November 1, All Saints’ Day. In reality, it should be observed the following day--All Souls’ Day--but Filipino Catholics have always marked the 1st of November as the day of ‘daun’. ‘Daun’ means an act of dedication or making an offering, and it is on this day that our deceased are remembered with gifts of flowers, prayers and visits from family members. Today, the term ‘undas’ which is of Spanish origin, is heard more often than ‘daun’ to refer to this season, and it is uncanny that ‘daun’ is almost an anagram of ‘undas’.

Who can forget the rites of ‘daun’ that begins almost always at home? Few days before the big day, our househelps would be making trips to the hardware to buy cheap water-soluble paint—Boncrex brand—that easily washes away in the rain. Even cheaper is kalburo (calcium carbide), which, when mixed with water becomes a paint substitute, but with a peculiar noxious smell. Armed with rags, grass cutters, and old palis tambu (recycled into paint brushes), they would troop to the old public cemetery to paint the puntud (tombs) of our family members, conveniently located right by the cemetery welcome arch.

Cemetery tending used to be a legitimate independent business, until private memorial parks took over. Men, women and even children were employed by families to take care of their family plots year-round and the job included weeding, watering plants and keeping the grave markers and statuaries clean. In the late 20s, freelancers could earn 50 centavos to 10 pesos a month per tomb, a decent salary in those times.

Cemeteries of old offer strange, eerie sights that often leave one reflecting on his own mortality. I remember, for example, this old tomb next to ours that was marked with a standing cement statue of what appeared to be a headless woman holding a wreath in her hands. As a youngster, I avoided going near that tomb and it was only when I was older that I learned it had a head—bowed down in an expression of profound grief. From where we sat, the statue appeared to be without a head—a pugut!

Of course, the Cementerio del Norte in Manila had more incredible and magnificent tombs to show. Here, presidents, diplomats, foreigners, heroes and other notable personages rest in massive art deco mausoleums guarded by angels, sylphs, gargoyles and other heavenly figures in cement and marble. But if these beautiful examples of mortuary art cause you to pause, the epigram on the gate of Betis Cemetery will make you ponder on life’s inevitability: “Aku ngeni, ika bukas” (My time to go, your turn tomorrow) so goes the grim reminder to all those who enter here.

Back at home, my mother would also be taking down the old picture frame of my Apu that hanged in our living room. Pictures of the dead were brought as well to the cemetery, to be placed on top of tombs, to visually identify the deceased. In the past, handmade coffins bore the names of the dead, painted on the side. Maybe they were made thus so that there’s no need to put a caption when the recuerdo de patay souvenir picture is taken! The famed coffin makers of Sto. Tomas, Pampanga could very well take a cue from this old quaint practice as part of their ‘customized’ casket design services!

To this day, memorial plaques of marble and granite—or lapidas-- are standard grave markers but the older ones that I see when I go around the semeteryu are more intricately made, some embellished with Spanish epitaphs like “Recuerdo de la Familia”, or with the more familiar D.O.M. (Deo, Optimo Maximo, or "To God, Best and Greatest"), R.I.P. (Rest in Peace) and S.L.N. (Suma Langit Nawa, although at one point, I was told that it meant “Sa Lagnat Namatay”, which gullible me believed for years!). In the 1920s through the 50s, lapidas could be ordered from talleres de escultura in Guagua and Betis or commissioned from Oriol Sculpture Works in Manila.

Then, as now, wreaths and flowers were major part of ‘daun’. For years, every end of October, my aunt from Baguio would send calla lilies by the bunches for our use. We would store these in buckets in the bathroom until they are brought out by my sister and mother on the eve of All Saints. For the next three hours, their dextrous hands would fashion memorial bouquets from these flowers, stuck on cut-up banana trunks with barbecue sticks, then supplemented with palm leaves and asparagus ferns plucked from our garden.

Memorial wreaths of old were more intricate, very similar to Mexican ones. They were created from flowers like amarrillos, zinnias, orchids, santan and chrysanthemums whose petals were often arranged to form words of condolences, as opposed to the use of ribbons today. The circular wreaths were then wrapped in clear cellophane and displayed for sale along the streets. Stands made of rattans were made to hold sprays of real flowers, but I also remember that we used plastic orchids for years as a cost-cutting measure.

Candles were no problems as they were easily available—my uncle ingeniously made candle holders from tin scraps, which he soldered together and which we used for quite awhile. Our Siopongco neighbors however had fancier lighting effects, spotlighting the Lourdes grotto that graced their family plot. To pass the day, I would go around tomb-hopping just like other children, asking for melted candle wax to be collected in a ball. We could use these later to wax our floors. Today, enterprising children collect candle wax for re-sell.

It used to be easy requesting your friendly neighborhood family priests to pray over the tombs of your deceased loved ones. You would often find them roving around the cemetery grounds, ready with their holy water bottles to bless the tombs. Of course, the in thing to do now is to put the names of the deceased in a prayer intention envelope and leave it at the parish office—with your money of course. In Betis, the custom of pa-siyam (nine day novena for the dead) is still practiced, with a twist. Prayer, flower, candle offerings and cemetery visits go on beyond Nov. 1, extending until Nov. 9, a unique tradition that speaks well of the town’s deep religiosity and love for their dearly departed.

That cannot be said of current ‘daun’ practices today, which put emphasis on crass commercialism and inappropriate revelry right inside the campo santo—the supposed holy grounds for the dead to rest. We see that on TV features every year, where people troop to the cemeteries with their food baskets and sound systems, gambling, drinking and eating the hours away to the blare of ear-splitting music.

Naturally, too, the most money is made out of the dead on the day specially set aside for them—All Saints’ Day. Never are candles and flowers so costly, never are jeeps and pedicabs so difficult to hire. Along the roads leading to the cemeteries, aside from the improvised tiendas, you can even find ‘karnabal’ rides and seedy shows, ready to fill the needs of the living on the day reserved to honor the deceased. The message of ‘daun’ may be lost on these people, but the cycle of life is certain to remind them that their time too, will come. “Aku ngeni, ika bukas”.

Sunday, May 2, 2010

*192. MSGR. JOSE R. DE LA CRUZ: Renaissance Man of the Cloth

FR. JOSE DE LA CRUZ, as a graduate of Sacred Theology of Santo Tomas University. Dated 1943.

FR. JOSE DE LA CRUZ, as a graduate of Sacred Theology of Santo Tomas University. Dated 1943.Recently, just a week after Good Friday 2010, Kapampangans mourned the loss of one of the most accomplished Kapampangan religious ever to come from the the province. Msgr. Jose Reyes de la Cruz passed away on 10 April 2010, almost month short of his 97th birthday. The good monsignor lived a long and full life, marked with brilliant career achievements not only as an extraordinary man of the cloth but also as a theologian, world traveler, literary and musical genius and a Catholic mass media practitioner.

The future monsignor was born in the sleepy barrio of San Matias, Guagua on 8 May 1913. His uncle, Fr. Vicente M. de la Cruz, was a well-known priest in Sta. Rita, and this must have also spurred him to answer his priestly calling. At age 15, he entered the San Jose Seminary as a high student and graduated as the class valedictorian. He continued to earn a Philosophy degree from the seminary and in just three years, graduated Summa Cum Laude.

The bright seminarian was sent to the International Gregorian University in Rome, but his frail health did not allow him to finish his studies there. He went back to the Philippines in 1937 and the following year, he enrolled at the Central Seminary of the University of Santo Tomas. In 1941, after graduating with a licentiate Summa Cum Laude, he was finally ordained as a priest. Two years later, he earned a doctorate degree in Sacred Theology, Magna Cum Laude. Not content with a doctorate, he also obtained a Bachelor of Laws from the pontifical university.

In the mid 40s, “Among Pepe” was assigned as the parish priest of Licab in Nueva Ecija. His other postings included San Marcelino in Zambales, Guagua and Bacolor. A seasoned global traveler, he has gone around the world 10 times, and has visited 37 countries in 18 separate trips. In Rome, he would act as a guide for visiting Filipino priests, often accommodating their requests for tours around the Vatican and its environs.

In 1952, he represented the Diocese of San Fernando in the International Conference of the Apostleship of Prayer and Nocturnal Adoration in Barcelona, Spain. In 1958, he attended the Centennial Celebration of the Lourdes apparition in France.

Back home, he helped in launching the crusade of Charity revolving around Virgen de los Remedios, the patroness of Pampanga. He anchored a radio program over DZPI Manila, using the show as channel for his catechism. He also became a columnist for several Catholic religious publications. Msgr. De la Cruz also served as the longtime parish priest of the Immaculate Conception Church of Guagua from 1957-1974, taking over Rev. Fr. Pedro Puno. While there, he livened up the local church scene by organizing the People’s Eucharistic League and activating the Cursillo Movement. He also improved the church, reconfiguring the altar area to make it circular, and adding on a golden monstrance to the church vessels, a precious find from is many travels.

In 1964, Among Pepe figured in a sensational criminal case in which 15 year old Corazon “Cosette” Tanjuaquio, daughter of a prominent Guagua family, was kidnapped for ransom. The perpetrators chose the priest to act as an emissary between them and the authorities. Several times, the courageous reverend volunteered to deliver the ransom money, often driving alone to the agreed-upon site, waiting long hours and even surviving a shooting attempt. The kidnappers were eventually apprehended.

A multi-dimensional Kapampangan, Among Pepe also dabbled in music and was adept in playing the violin. During his student days, he was named as the Orchestra Conductor of the San Jose Seminary and the Central Seminary of U.S.T. He was also an outstanding poet and prodigious writer, composing inspiring prayers in English, noted for their intuitive and vivid sensitivity. On 26 August 1969, Msgr. Dela Cruz delivered the invocation of the World Congress of Poets held in Manila.

In the 1980s, Msgr. De la Cruz continued to write religious features and columns while ably assisting Archbishop Oscar V. Cruz of the Archdiocese of San Fernando. His last assignment was at the St. Jude Thaddeus Parish in San Agustin, San Fernando. About 6 years ago, I had the opportunity to meet him in his St. Jude home. Though slowed down with age and needing assistance, his mind remained clear and alert, and he talked to us in a gentle, but commanding tone in impeccable English. In his little room, he sat and chatted with us, surrounded with mementos of his life—stacks and shelves of well-thumbed books, diplomas on the wall and his favorite violin.

Reflecting on his death, I am drawn once more to one prayer he wrote, one of the most lyrical, most touching ever composed:

“Lord, let me find you in the angelic smile of innocent children..

And in the measured pace of old age.

Let me hear you in the aged canticles of singing streams..

And in the soft murmur of evening breezes..

Lord, let me find you and hear you, everywhere I go

And at every moment of my waking hours,

For the whole universe is Your image and all good music s your singing voice..

This, my humble creator, is my humble prayer. AMEN.

In the bosom of his Lord, we will find the good monsignor again.

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

*183. THE PROCESSIONS OF MALELDO

FOLLOW YOUR FAITH. A famil in Centra Luzon rolls out its carroza with the heirloom image of Sta.Maria Jacobe, one of the women who visited the tomb of Christ, for the annual Holy Week procession. Ca. mid 1920s.

FOLLOW YOUR FAITH. A famil in Centra Luzon rolls out its carroza with the heirloom image of Sta.Maria Jacobe, one of the women who visited the tomb of Christ, for the annual Holy Week procession. Ca. mid 1920s.The season of Lent officially begins on Ash Wednesday, a day of marked with abstinence, personal sacrifice and austerity. But somehow, or so it seems, during Semana Santa (Holy Week), all thoughts of economics and abject simplicity vanish as a people’s religious fervor find release in the opulent and dramatic prusisyons (or limbun) that feature a long parade of life-size heirloom santos and complex tableaus, visualizing the events of the Passion. Introduced to the Islands by our Spanish colonizers, holy processions have evolved from a simple act of veneration to complex showcases of ritual pageantry.

In terms of religious revelry, Pampanga offers some of the country’s more unique expressions of faith during Maleldo (Holy Week). Other than the display of blood and gore by magdarames (flagellants) culminating in actual and shocking crucifixions, the prusisyons (or limbuns )of old Kapampangan towns provide stunning spectacles featuring antique sculpted imagenes dressed in gold-embroidered vestments, crowned with gem-encrusted halos and diadems, festooned with dazzling lights and arrayed on flower-bedecked carrozas of silver.

Indeed, the list of the most treasured and remarkable santos that go on “limbun” during Maleldo is long. In Arayat, the age-old Manalangin (Agony in the Garden) tableau of the Medina family shows a small lithe angel with silver wings attired in short pants. In Guagua, which reputedly has the best processional line up, the ivory Dolorosa of the Limsons and the Sto. Entierro—figure of the dead Christ in its own stately funeral bier---are the images to watch. Nearby Sta. Rita boasts of an ancient calandra (owned by the Manalangs) still complete with its original and intricate silver fittings, lit by delicate antique tulip-shaped glass globes.

Angeles has its own Apung Mamacalulu (Sto. Entierro, owned by the Dayrits) which figured in a controversial 1929 Good Friday procession that ended in its kidnapping . It took the Supreme Court to resolve the issue of its ownership. While Apalit has an exquisite Magdalena and Mabalacat’s jewel is a beautiful Veronica, Lubao has a San Pedro that rides a boat-shaped carroza. Fernandinos in the capital city meanwhile, take pride in the images of the Sorrowful Virgin and Peter, handiworks of the country’s foremost santero, Maximo Vicente and the 19th c. Misericodia Christ image of the Rodriguezes.

Equally arresting are other quaint processional rituals such as that practiced in Bacolor. On Good Friday, handpicked representatives of prominent families take to the processional route dressed in black hoods while bearing the different symbols of the Passion—ladder, spear, whip, robe, etc.—on poles. This practice, called “paso”—has been a tradition in this town for as long as one can remember.

Other Pampanga towns like Betis and Mabalacat, also stage their own “dakit cordero” on Holy Thursday, where a “lamb” , handmade from cotton or from edible ingredients like yam, is brought to the church in a short procession, prefacing the eucharistic meal.

There are no signs that the Kapampangan’s interest in “limbuns” is waning, as evidenced by the growing number of images and the longer processions that take to the town streets each year. Even not-too-popular figures such as Sta. Maria Jacobe, Nicodemus, Jose de Arimatea are being added to the line-up. Blame it on his fierce and unflagging devotion to his God. Or his penchant for divine excess. One can also point to the pool of talented Kapampangan artisans who wield their chisels and paint brushes who create with ease and skill, these precious objects of veneration. Whatever the reason, we, Kapampangans, can continue our walks of faith content in the thought that our revered religious traditions will live on.

Tuesday, January 26, 2010

*179. PATRIOTISM IN A PUFF

LIGHT MY FIRE. Then, as now, smoking was a favorite Kapampangan past time. It also spawned a backyard industry in many Pampanga towns, where contracted workers rolled and wrapped cigars in lithographed paper packages such as this "La Pampanguena" brand from Angeles. ca. 1920s.

Cigar and cigarette manufacturing in our islands officially began in 1782, under the tobacco monopoly introduced by Gov. Jose Basco y Vargas. The 1st factory was located in Binondo, with space provided rent-free to the government by the Dominicans. Under the monopoly system, the government had complete control of the cultivation (only select provinces like Bulacan, Nueva Ecija and Pampanga were authorized to grow tobacco), processing and manufacturing of cigars and cigarillos. Thus began the first application of the factory system in the Philippines, where thousands of laborers, mostly women, reported to a central place of work, which were often cramped, hot and humid. Nevertheless, factories provided livelihood and the tobacco business accounted for the government’s biggest share of revenue.

When the monopoly ended 10 years later, private entrepreneurs rushed to cash in on the lucrative cigar/cigarette industry, setting up factories in Manila and nearby provinces. To protect consumers from fly-by-night operations, a cigar tax was imposed. Quality cigars were churned out by the millions by Alhambra and Tabacalera.

The cigar industry, however, failed to respond to changing consumer preferences in smoking, which was about the time the Americans arrived. When cigar production dwindled and mechanization of cigarette processing was launched, Filipinos switched to cigarettes or cigarillos. Cigarette companies like La Paz y Buenviaje produced a variety of brands, like the “Dollar” brand, capturing a whole new market of “sajonistas” altogether.

Turn-of-the-century cigarettes were often distinctively packaged in batches of 24s-30s, in wrappers with detailed graphics such as these examples of Pampanga provenance. Local entrepreneurs probably bought processed cigar leaves and engaged backyard workers to roll and wrap cigarettes in these 2-color, lithographed packages carrying assorted visual themes, often irrelevant to the product, ranging from the patriotic (pictures of heroes, Katipunan) to the mythical and romantic.

Notable example is the “Sinukuan” brand, from Plaza Sto. Tomas Pampanga, which has a truly local Kapampangan theme, showing a barebreasted Mariang Sinukuan holding a billowing flag with a range of mountains in the background. The back panel shows a Aeta workers gathering palm leaves in the middle of a tobacco plantation (!) with their leader welcoming a cigarette-smoking stranger.

A unique Betis wrapper, "La Reina Malaya" (The Malayan Queen), on the other hand, contains a nationalist verse that calls upon Filipinos to patronize Philippine-made products and not those made by our colonizers--highly seditious stuff on print!

On the other hand, “Las Dos Hermanas” brand from Bacolor is no different from the way we name small businesses even today (as in “3 Sisters Carinderia”).

The inappropriate “Ates” brand also carries the name ‘Nemecio Leonardo’, who may have been the entrepreneur, the same way “La Soledad” banners the name ‘Maria Consolacion’ of Betis. “Los Enamorados” (The Enamoured Ones) from the Fabrica de Pampanga Plaza Guagua simply defies explanation with a European boating scene that hints of a menage a trois, in the middle of the sea abloom with lotus flowers!

Today, these cigarette wrappers are being collected not just for their artistic merit, but also for their value as cultural ephemera, defining our taste for leisure and recreation under our colonizers.

Sunday, August 16, 2009

*158. Shall We Dance?: TERAK KAPAMPANGAN

TAKE THE LEAD. A folk dance presentation by San Simon Elementary children nattily dressed in Maria Clara costumes and barong tagalog. Ca. 1930s.

TAKE THE LEAD. A folk dance presentation by San Simon Elementary children nattily dressed in Maria Clara costumes and barong tagalog. Ca. 1930s.One of the most horrifying experiences to happen to a student with two left feet is to be picked as one of the folk dancers in a high school day presentation. I not only remember the moment of selection, but also the title of the dance—it was a strangely-named dance called “Pandanggo Buraweño". Thank God, we didn’t have to wear funny costumes like the “Manlalatik” dancers and their ‘coconut bras’ or use unwieldy props like the sticks for “Sakuting”. It was just a simple dance that we practiced after school hours, and our performance was just as simple and forgettable.

Our Philippine dance tradition started long before the Spaniards reached our shores. When Magellan arrived in Cebu, chronicler Antonio de Pigafetta took note of the song-and-dance entertainment provided by the natives. Ritualistic dances such as those done by babaylans and the hunting dances of ethnic tribes are raw expressions of the Filipino soul.

Indeed, there were dances for just about everything—birth, courtship, wedding, religion, death—and the coming of colonizers further enriched the choreography of our dances. From Spain came the jota, pandanggo and habanera while the French contributed the rigodon and the minuete (minuet). In Ilocos, a dance called Ba-Ingles was obviously adapted from Americans.

Kapampangans with their nimble feet and love for music and rhythms have also taken to dancing early on. Our few signature dances have not reached the level of national awareness the way the “tinikling”, “singkil” and even the fairly new “itik-itik” have, which had the benefit of being performed by professional troupes the world over----not yet, anyway. But with the recent exposures of our local festivals on television, Pampanga’s dances are becoming hit attractions.

No other Philippine dance is as frenetic as the kuraldal, a dance originally performed in Sasmuan on Dec. 13 to honor its patron, Santa Lucia. They say it’s Pampanga’s counterpart of the Obando fertility dance—in kuraldal, people dance not only for good health, but barren women also ask for babies. But kuraldal is wilder, characterized by swaying and jumping to the beat of kuraldal music. People dance non-stop, and the infectious beat can sometimes have a hypnotic effect on the participants, who enter a trance-like state while dancing for hours. The kuraldal practice has also spilled over to other Pampanga towns like Betis, in which the 24 handpicked participants are expected to teach the dance to their children.

The origin of kuraldal is not really known; it may have originated from tribal dances that eventually melded into Christian rites. Or the Augustinian missionaries may have introduced it as part of their para-liturgical rituals in bringing the faith from inside the church to the outside community.

Another dance performed in Pampanga is “katlu”, which is also known in nearby Bulacan and Nueva Ecija. When hardworking lads came to help the rural lasses pound their palay on the mortar (asung) and pestle (alung), a new dance was born, with couples moving to the beat of pounding rice. “Katlu” was quickly transformed into a courtship dance ritual.

Then there’s the “sapatya”, originally presented by farmers during the harvest season. Characterized by graceful steps and hand movements, it is believed to have been derived from the Spanish, “zapateado”, or shod with shoes. Sapatya has evolved into many versions, and there is one, performed in Bacolor on the Pasig-Potrero river, where ladies, wearing buri hats, dance precariously on a bangka. In Porac, the dancing of sapatya is accompanied by the singing of pulosa, further living up the moment.

Dancing has come a long way since, and through the years, the influence of global pop culture has changed the way we move on the dancefloor. Through the years, we have waltzed, tangoed, boogied, jerked, shimmied, elephant walked, salsa-ed, and spaghetti-ed our way to fun, fitness and frenzy. That is all very good, but once in a while, when your twinkletoes are in the mood to learn something new—try learning something old. Like the kuraldal. Or the sapatya. Or katlu. It’s a step towards perpetuating our rich tradition for the next generation to appreciate. I can’t think of a better move.

Let’s dance to that!

Labels:

Bacolor,

Betis,

culture and tradition,

Pampanga,

Pampanga arts,

Porac,

Sasmuan,

social history

Friday, May 15, 2009

*149. ON THE SAME BOAT: Cruising Pampanga’s Waterworld

ROW, ROW, ROW YOUR BOAT. Candaba's townsfolk negotiate the flooded waters of their town, using a trustworthy bangka, a necessary mode of transport for those living in low-lying Pampanga towns. Ca. 1927.

ROW, ROW, ROW YOUR BOAT. Candaba's townsfolk negotiate the flooded waters of their town, using a trustworthy bangka, a necessary mode of transport for those living in low-lying Pampanga towns. Ca. 1927.Kapampangans, being riverbank dwellers, have taken to water like ducks to a pond. The province’s complex network of river highways, its swamplands and river deltas have shaped the way many Kapampangans lived, traveled, devised their leisure and earned their keep. These bodies of water located all over Pampanga have been creating ripples of history since time immemorial. Through a river, Tarik Soliman and his fleet of boats sailed from Macabebe to Bangkusay to meet his heroic death. When the Grand Duke of Russia, Alexis Alexandrovich visited Apalit, he cruised along Pampanga River all the way to the home of his hosts, the Arnedos, whose mansion had a small pier.

Kapampangan traders from Candaba, Apalit, Bacolor and Guagua used the river channels and tributaries to ferry livestock and farm produce to the canals of Manila. Barrios were named according to their proximity to water: Guagua (from ‘wawa', mouth of a river), Macabebe (“bebe”- bordering the river bank), Sapa Libutad, Sapang Bato and Sapang Balen. Fiesta rites revolved around water as in the “libad” (fluvial procession) of Apalit’s Apu Iru.

Taming the waters was a necessity for riverine residents and those living in low-lying areas. Early Kapampangans, especially those from Candaba and the coastal villages of Sasmuan, mastered boatmaking, fashioning bangkas from hardwood trees like molave, tanguili, or guijo. Balacat trees were preferred for their straight posts that were used as masts.

Boat types included the parau (a large passenger or cargo boat), dunai (a simple boat propelled by a bagse or a paddle), casco (a covered cargo raft) and baluto (canoe). Even steamships were not unknown to Kapampangans as they were seen regularly cruising the waters of Guagua, now known as Dalan Bapor.

Directions were reckoned according to the directional flow of rivers. When one says “Pauli na ku”, he actually means he was riding a boat to go downstream. “Lumaut ku”, means one is going out to sea; today it means to go somewhere distant. “Luslus” means to head south by boat, towards Manila Bay, which, today has been modified to mean long distance travel, even by land.

In the late 19th century, passenger boats set sail every Monday, Wednesday and Friday from Guagua to Manila and back. The fare was $2.50, one way. With our modern and time-saving expressways linking whole towns and provinces to key cities like Manila, travel by bangka has fallen from passenger favor in recent times, being demanded when catastrophic floods occur. But for towns like Candaba, Macabebe, Sasmuan, Minalin, Masantol and Bacolor—where cyclical floodings no longer surprise, bangkas continue to be rowed, sailed and paddled, a practice that has become a way of life for the “pampang” people.

Labels:

Angeles,

Betis,

Floridablanca,

Lubao,

Pampanga,

Pampanga commerce,

Pampanga industrial arts,

Philippines,

Porac

*148. MUEBLES DE PAMPANGA

FULLY FURNISHED. An officer's house in Clark Field, furnished with Pampanga-made wicker furniture, including a rocking chair, a writing desk, cabinets and a lounge chair.

FULLY FURNISHED. An officer's house in Clark Field, furnished with Pampanga-made wicker furniture, including a rocking chair, a writing desk, cabinets and a lounge chair.The center of Pampanga's woodworking industry is Betis, which has long been recognized as one of 11 Pampanga's most important towns at the turn of the century. Its name is derived from a first class timber tree, betis (Bassia betis merr.). The abundant supply of wood--old boatmakers remember the days when logs from the forests of Alta Pampanga and Bataan were floated on the old Betis River--gave rise to a furniture industry that has thrived and survved with time.

Indeed, “dukit Betis” has become synonymous with fine quality, detailed woodworks that counts not just fine furniture but also religious carvings and images. Besides Betis, lumbering was done in Lubao, Floridablanca and Porac. Most of the lumber is consumed locally, but some is exported to Manila. Lumber was also sourced from trees cut in Magalang and Arayat, like rattan, mitla, balacat, balanti, balete, baticuling and bangcal—materials ideal for furniture making.

Colonial furniture made locally adapted European styles popular in those times—rococo, baroque, neo-classical, although some elements of Chinese influences were integrated into the design. The use of bone inlays to decorate wood furniture became a trend in the 18th century, and Betis craftsmen were singled out for their skill. Historian Mariano Henson noted that Betis anloagues (woodworkers) were masters in the art of inlaying carved furniture with mother-of-pearl, bone and hardwood.

The American regime introduced new art forms like Art Deco and sleek, streamlined furniture pieces like Ambassador sets and Cleopatra dresser became the rage in the 1920 through the 40s. Americans took to furniture made from indigenous materials. Officers’ houses in Stotsenburg were furnished with attractive living room sets made of hardy rattan, which can be bent into different shapes, even mimicking expensive bentwood pieces from Austria. Their porches featured lounge chairs made from mountain bamboo (bulu) or with sillones and butacas with sulihiya (cane-woven) seats. American ladies sat on gorgeous peacock chairs of wicker , virtual thrones for the queen of the house.

Commercial furniture shops sprouted all over Pampanga during the peacetime years catering to different tastes and whims. In Guagua, Moderna Furniture manufactured “aparadores, catres, tocadores, vegillas, sillas made of narra and tanguile”, all with “first class workmanship and reasonable prices”. In Angeles, Sibug Furniture on Calle Rizal was the place to look for the latest furniture styles. Mabalacat had its won Bazar y Tableria de Tuazon y Lim, a “fabrica de diferentes clases de muebles”( a factory of different kinds of furniture). On Calle N. Domingo in San Juan, two enterprising Kapampangans, Clemente Dungo and Estanislao Dalusung opened Pampanga Furniture Company.

The rise of Clark Field in the 50s through the 1970s induced the flourishing of Pampanga’s furniture industry. Balibago in Angeles was lined with furniture shops with pieces catering to American taste. American servicemen particularly found South Pacific design themes appealing and so, rattan furniture gained more popularity, with cushions sporting floral and palm leaf upholstery. Kon Tiki masks, monkeypod pieces, dinettes with lazy susans and carved coffeetable trunks graced American as well as Kapampangan homes.

A notable woodworker who worked during this period was the versatile Juan Flores (b. 9 September 1900) of Sta. Ursula, Betis. He not only sculpted figures of heroes and saints but also made carved furniture that incorporated local patterns like bulabulaklak (floral) and kulakulate (design simulating vines). Flores and his platoon of Betis carvers re-did the guest rooms and various suites of Malacanang, furnishing them with exquisite furniture sets and various Renaissance style carved ornamentations.

Today, the Pampanga furniture industry is alive and well. One only has to see the many talyers lining the Olongapo-Gapan and Bacolor-Guagua Roads, with their roadside displays serving as showcases of Kapampangan woodworking expertise. Thanks also to successful, modern day entrepreneurs and furniture exporters like Myrna and Jose Bituin of Betis Crafts, the world has started to see what hard-working Kapampangan hands and creative Kapampangan minds are capable of.

Monday, March 30, 2009

*137. BLESSED BE GOD: The Religious of Betis

SEMINARISTAS DE PAMPANGA. A group of Kapampangan seminarinas from San Carlos Seminary pose for a souvenir picture. Future priests Andres Bituin (1st person on top row) and Felipe Roque (4th from right, 2nd row) are from Betis.