Sunday, February 3, 2013

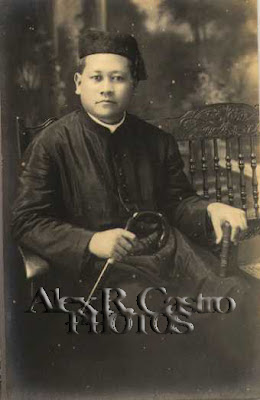

*322. His Seminary Yearbook: BISHOP TEODORO C. BACANI, JR.

IT IS RIGHT TO GIVE HIM THANKS AND PRAISE. The future bishop of Manila, as a fresh graduate of Philosophy of San Jose Seminary, 1961, Teodoro C. Bacani Jr. of Guagua.

The first time I came face to face with Bishop Teodoro “Ted” Bacani, Jr. was when he officiated the memorial mass of my uncle, Msgr. Manuel Valdez del Rosario, who passed away in 1987. A longtime priest of San Roque Parish in Blumentritt, Padre Maning had been a bosom friend of many known personalities and celebrities, including Bishop Ted, a fellow Kapampangan, who was originally from Guagua. Bishop Ted provided a light moment amidst the somber atmosphere by recounting how, upon alighting from his car, a crowd had looked and pointed at him, screaming: “Yoyoy Villame is here!”. The people inside the church chuckled at his anecdote, knowing well that Bishop Ted was popular in his won right, a powerful voice who never feared of speaking up in the days of People Power.

Born on 16 January 1940 in Manila, he went to various schools in Manila; at age 6, enrolled at the Instituto de Mujeres (Roseville College). Upon graduation, he went to Letran and earned his High School diploma in 1956. he entered San Jose Seminary in 1956, and began his priestly training, earning a Philosophy degree in 1961. He remained in San Jose to pursue his masteral degree in Philosophy for two years. On 21 December 1965, Ted officially became a priest with his sacerdotal ordination at the Manila Cathedral.

His first assignment was as an assistant parish priest at San Antonio, Zambales, a post which he held for two years. His superiors took note of his promise, and the next year, he was sent off to Rome to study Dogmatic Theology at the Angelicum University, finishing his doctorate in 1971. Upon his return, he resumed his ministerial duties in San Narciso, Zambales till 1976, when he became the Parish Priest and School Director of St. James, in Subic, from 1976-79.

After that stint, Fr. Ted became a professor of Theology at the San Carlos Seminary, assuming the deanship from 1982-83, on top of being a Theology consultant of the Archdiocese of Manila. On 6 March 1984, he was appointed Titular Bishop of Gauriana at age 44, and his ordination as Bishop took place on 12 April 1984. His consecrators included Archbishop Bruno Torpigliani, Bishop Amado Paulino and Archbishop Paciano Basilio Aniceto.

As Bishop of the Ecclesiastical District of Manila, he was involved in many major activities—from chairing the Archdiocesan Commission on Marriage and Family Life Ministries (1984) and the National Pastoral Planning Committee (1985) to serving as a parish priest of San Fernando Dilao of Paco and acting as the Spiritual Director of the Mother Butler Guild. In the heady days of the People Power Revolution, Bishop Ted was the Chairman of the CBCP Committee on Public Affairs in 1986.

On 7 December 2002, he was appointed Bishop of Novaliches. On April 2003, his personal secretary filed a sexual harassment case against him which forced him to resign his post, later that year in November. While remaining a bishop in good standing with all rights and powers as bishop, he was not given charge of any particular diocese.

Unfazed by these turn of events,the now-retired bishop emeritus remains an authoritative force in the church, speaking his mind about current issues--from the RH bill, divorce law to boring sermons and over-emphasis on Santa Claus. Recently, Bishop Ted challenged politicians to pass a law against political dynasties to prove their sincerity in serving the country in the 2013 elections.

Thursday, October 4, 2012

*312. THE GILDED AGE OF ALTARS

When Augustinian missionaries descended upon Pampanga, they lost no time embarking on building churches. This religious order—first to arrive with Legazpi’s expeditionary group in 1565—is credited with constructing the most number of churches in the country.

The first visitas were made from indigenous materials—nipa, bamboo, hardwood trees—but with grants from the Real Hacienda, income from church services, free labor from the system of polo y servicio, churches soon evolved and grew into magnificent structures, with lavish decorations that rivalled those of Europe.

Nowhere is this more evident in the main altars of old Pampanga churches. Apparently, Filipinos and Spaniards shared a common interest in the decorative arts; just 50 years after Manila’s foundation, it was noted that the progressive city had churches adorned with rich silk fabrics and altar fronts covered with expensive silver.

Indeed, the altar became the most outstanding feature of the church in terms of artistry and opulence, for they were designed to attract attention and direct the gaze of the devotee to the tabernacle that housed the Holy Eucharist. The sagrario (tabernacle) was flanked by gradas (tiered panels) where decorations like ramilletes ( bouquets of silver or wood) and silver candeleros (candle holders) were placed.

The altar mayor featured the mantel-covered mesa altar, on which the priest said Mass, his back towards the audience. The Second Vatican Council of 1962 made significant reforms in the conduct of liturgical services, including changes in the physical make-up of the altar space. Altar tables were moved to the foreground, so that priests can celebrate the Mass, facing the audience. Retained were the magnificent retablos behind the mesa altar, frontal structures carved with period decorations and designed with nichos to house santos of wood and ivory, as well as paintings and relieves (relief carvings) showing Biblical and other holy scenes—all meant as visual aids in the missionaries’ oral teachings and in their attempt to convert people to Christianity.

The churches of Pampanga reflected the spirit of this gilded age, the combined power and glory of Art and Faith serving a higher purpose. The church of Lubao for instance, has a retablo mayor carved in florid Baroque style, with Augustinian santos enshrined in niches, leading one admirer to write that it is ”one of the most sumptuous in the Islands”.

The Santiago Apostol Church in Betis, likewise, boasts of a baroque wooden retablo carved with the most refined details, and infused with rocaille motifs—shells, curlicues, sinuous floral patterns. Once installed in the central niche was the figure of the patron—St. James as a peregrine, or pilgrim, now replaced with the Risen Christ. Angels playing musical instruments are scattered about the retablo, with the all-seeing God the Father, lording it all.

The church of Bacolor, dedicated to San Guillermo and touted as Pampanga’s biggest church in 1897, once had rich silver works with beautifully-gold leafed altar. The sunken retablos have all been restored after the Pinatubo eruption—sans the real gold gilt. Apalit has an intricately ornamented altar surmounted by a dome, replicating the church’s signature dome feature. The altar of San Simon is carved with floral splendor, with the figure of the Holy Spirit hovering above. Sta. Rita’s claim to fame was once its gilded main altar, while that of Masantol had Renaissance style carvings. The ancient church of San Luis also has an impressive retablo done in baroque, while Guagua’s altar frontals were once adorned with beaten silver (pukpok), made from precious silver coins.

The grandeur of our altars have been somehow dimmed by the ravages of time and the cataclysmic workings of nature—floods, earthquakes, volcanic upheavals. But though begrimed with dust, covered in lahar and engulfed in flood waters, it is before these altars that we always fall on our knees, intone our prayers for succor and help--and find our faith again.

Monday, July 23, 2012

*303. Pampanga’s Churches: SAN PEDRO APOSTOL CHURCH, Apalit

The bordertown of Apalit, founded by Augustinians in 1590, is built on swamplands by the banks of the great Pampanga River. Its first rudimentary church was probably started by Fr. Juan Cabello, who served the town on several occasions between 1641-45. A new church was also begun by Fr. Simon de Alarcia of stone and brick, which was never completed.

The foundation of the present church was laid by Fr. Antonio Redondo, the town’s parish priest who had it built for P40,000 following the plans of a public works official, Ramon Hermosa. For seven years (1876-1883) and under Guagua foreman Mariano Santos, the “pride of Pampanga, an indelible tribute to Fr. Redondo and the people of Apalit”was built and inaugurated in a series of ceremonies on 28, 29 and 30 June 1883.

The good father actually saved P10,000 as he paid the workers from his personal funds and astutely bought the materials himself. When the masons ran out of sand and bricks, Fr. Redondo would solicit the assistance of the town people by asking the sacristan to ring the bells. This way, he gathered enough volunteers to haul in sand from the river.

The completed church measures 59 meters long and 14 meters wide. Dedicated to the town patron, St. Peter,the church is built along neo-classic lines, with a graceful rounded pediment marking its façade, topped with a huge rose window—in contrast to the simple Doric pilasters and the two rectangular bell towers with pagoda roofs.

Its signature dome rises to about 27 meters and is supported by torales arches, with openings to light the church. Protective grills capped the doorway as well as the 3 circular rose windows on the church front. The church interior was decorated by an Apalit native, a pupil of the Italian painter Alberoni.

The feast of San Pedro or “Apo Iru”, is celebrated with ardour every June 29, including a raucous fluvial procession (“libad”) along Pampanga River. The seated ivory figure of “Apu Iru”—an antique ivory representation of the apostle attired as a Pope—is transferred from its Capalangan shrine to the Church, where it stays during the fiesta days until it is brought out for the annual “limbun”. From there, the beloved Apu is installed on a water pagoda for the traditional river festivities, a unique honor given to their patron who has given much to Apaliteños—a town, a home, a church and a colourful history.

Monday, April 2, 2012

*288. The Seminary Years of REV. FR. TEODORO S. TANTENGCO

THE CHOSEN. Teodoro Tantengco of Angeles was one of 12 seminarians who started their priestly studies at the San Carlos Seminary beginning in 1908. Eight years later, he was ordained as a priest. He was the long-time cura parocco of San Simon.

THE CHOSEN. Teodoro Tantengco of Angeles was one of 12 seminarians who started their priestly studies at the San Carlos Seminary beginning in 1908. Eight years later, he was ordained as a priest. He was the long-time cura parocco of San Simon. In 1908, twelve new seminarians entered the august halls of the Conciliar San Carlos, the first diocesan seminary founded in the Philippines. That time, the seminary was located along Arzobispo Street in Intramuros, beside the new San Ignacio Church. Three years earlier, the American Archbishop Jeremiah Harty had turned over the administration of the premiere seminary in the country to the Jesuits.

Of the 12 seminaristas, two were full-blooded Kapampangans and both from the town of Angeles—Felipe de Guzman and Teodoro Tantengco y Sanchez. Teodoro had entered just two months ahead of Felipe, on 1 July 1908. San Carlos had quite a substantial number of Kapampangan seminaristas enrolled even in those years, coming fromsuch towns as Betis (Victoriano Basco, Mariano Sunglao, Alberto Roque, Mateo Vitug); Sta. Rita (Anacleto David, Pablo Camilo, Eusebio Guanlao, Mariano Trifon Carlos, Prudencio David); Macabebe (Brigido Panlilio, Atanacio Hernandez, Maximo Manuguid, Pedro Jaime); Bacolor (Rodolfo Fajardo, Tomas Dimacali, Vicente Neri); Porac (Mariano Santos); Angeles (Pablo Tablante); Guagua (Laureano de los Reyes) and Candaba (Lucas de Ocampo).

Seminary life was conducted under the watchful eye of the Rector, Fr. Pio Pi and the Minister, Fr. Mariano Juan. Teodoro and his classmates were drilled in Liturgy, Music, English and Ascetics. Moral Theology and Philosophy were taught at santo Tomas while other courses like Math, Greek, French and even Gregorian Chants were also offered. Discipline was exact; some form of corporal punishment were meted out for acts of disobedience—like being put on silence and making public retractions of some kind.

Out of the classrooms, the Carlistas were employed in the Cathedral services and liturgical events, like in the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Pius X as a priest. The seminaristas assisted in the altar services at the mass officiated at the Manila Cathedral. Similarly, the class were mobilized to attend to Archbishop Michael Kelly from Sydney, Australia who had come to Manila for a short visit.

There was no rest during their vacation as Teodoro took classes in Latin, English and Tagalog, even as the superiors organized trips to Sta. Rita, Angeles, Dolores, Porac and Guagua. There were all-day picnics and excursions in Cainta, Cavite, Malabon, San Pedro Makati, Sta. Ana and at the hacienda of a certain Captain Narciso in Orani. Regular “dias de campo” were scheduled in Pasay and Malabon, where the youths swam, played with their bands and refreshed themselves with tuba, melons and ‘agua fresca’.

On 10 April 1910, the Carlistas took part in a historic church event which saw the establishment of four dioceses by Pius X—Calbayog, Lipa, Tuguegarao and Zamboanga. The seminarians were in full attendance to mark this important occasion for the Philippine church. The next year, the seminaristas were allowed to attend the Manila Carnival from Feb. 21-28 at Luneta, where they thrilled to the sight of the aerial acrobatics performed by American pilot Mars.

Teodoro and his classmates were taken by surprise on 17 August 1911, when they received orders from Archbishop Harty to transfer all San Carlos seminarians to the Seminario de San Francisco Javier (the old Colegio de San Jose) located along Padre Faura St. Teodoro was one of 30 seminarians who moved to San Javier, a merger-transfer that would last for 2 years, until the seminary closed in 1913.

With the termination of the Jesuit administration, the seminarians made their final move to a refurbished building in Mandaluyong, which was constructed by Augustinians in 1716 and abandoned in 1900. The Vincentian fathers (Congregation of the Mission) took over the management of the new site of Seminario de San Carlos.

It was here that Teodoro Tantengco, finished his priestly studies which culminated in his ordination in 1916. He was assigned immediately back to his home province in Pampanga, first as assistant priest of Masantol, then as the cura parocco of San Simon which he served for many fruitful years. In 1947, he was in Tayuman, Sta. Cruz.

The accomplished and well-loved priest passed away in San Fernando in 1954. A nephew, Betis-born Teodulfo Tantengco followed in his footsteps, enrolling in his uncle’s alma mater and, after ordination, served various parishes like Arayat and Dau, Mabalacat, Pampanga until his death in 1999.

Sunday, February 5, 2012

*280. His First Mass: FR. VICENTE MALIG CORONEL

FATHER ALMIGHTY. New priest Fr. Vicente Malig Coronel of Betis, finished his priestly studies at San Carlos Seminary and went on to become a familiar figure in Pampanga's religious scene.

FATHER ALMIGHTY. New priest Fr. Vicente Malig Coronel of Betis, finished his priestly studies at San Carlos Seminary and went on to become a familiar figure in Pampanga's religious scene. A new priest’s sacerdotal ordination is always a joyous and memorable occasion, a culmination of his seminary studies necessary to fulfill his holy calling. But his first thanksgiving mass takes on an even extraordinary significance for it marks his assumption of a new role--that of God’s chosen apostle-- anointed to preach and spread the good news of His Salvation.

On Easter Monday, 19 April 1954, Fr. Vicente Malig Coronel had the privilege of celebrating his first Solemn High Mass of Thanksgiving, and we have his souvenir card to remember that special day in the young priest’s life.

Betis-born Vicente, was one of the children of Gaudencio David Coronel, which also included Rodolfo, Gerardo, Santos and Dominga . His vocation was shaped early by his family and town, which prides itself in having produced the most number of priests than any other Pampanga town. He went to pursue his studies at the San Carlos Seminary, which had quite a sizable number of Kapampangan seminarians who even organized themselves into the Academiang Pampangueña.

On that fateful day at the same church where he served as an altar boy--the Church of Santiago Apostol of Betis, the neo-presbyter celebrated his own Mass at exactly 8:00 in the morning. Fr. Coronel was assisted by Rt. Rev. Msgr. Cosme P. Bituin who would, in the same year, be his superior in Angeles. Serving as Deacon and Subdeacon respectively were Neo-Pbtr. Severino G. Casas and Alejandro O. Ocampo. The assigned Preacher was the Very Rev. Santiago G. Guanlao. In charge with the Thurifer was Minorist Jose C. Guiao. Seminarians from U.S.T. served as Acolytes while the Torchbearers were his schoolmates from San Carlos Seminary. The Mater Boni Consilii Choir provided the music while Very Rev. Fidel M. Dabu hosted the ceremonies.

The sponsors of Fr. Coronel at this Mass were Msgr. Cosme Bituin, Sir Knight German R. Songco and Dña. Carmen Coronel Pecson. Immediately after the Mass, a fraternal reunion was held at the Coronel family residence.

After his ordination, Fr. Coronel was assigned as the Assistant Parish Priest, of Angeles in 1954. Together with Frs. Alfredo Lorenzo and Maximino Manuguid, Fr. Malig helped Msgr. Cosme P. Bituin run the affairs of the Sto. Rosario Church, proving his dedication in serving Angeleños for many years. One highlight of his religious career was his special audience and blessing of His Holiness Pope John XXIII on 29 July 1959, at his summer residence in Castel Gandolfo in Rome.

From Angeles, he was assigned in Tarlac and also had a stint at Our Lady of Penafrancia in Manila from 1976-1983, Fr. Coronel passed away on 22 June 1998.

“You have not chosen Me, but I have chosen you”—John 6, 16.

Sunday, July 10, 2011

*258. Pampanga Churches: STA. ANA CHURCH

GRAND OLD STA. ANA CHURCH. One of Pampanga's best-looking churches, was constructed from different materials sourced from all over the region. Its present foundation was begun in 1853. From the Augustinian Archives. Late 19th c.

GRAND OLD STA. ANA CHURCH. One of Pampanga's best-looking churches, was constructed from different materials sourced from all over the region. Its present foundation was begun in 1853. From the Augustinian Archives. Late 19th c.

The Sta. Ana Church might as well be the equivalent of the Manila’s Binondo Church –which, at least externally look the same, if not for the placement of their belfries. Wide, massive and spacious, the church, with its fenced courtyard, sits right in the center of the town, which began as a flat land called Pinpin, named after a prominent Chinese mestizo resident of the area.

Nestled near Arayat, Candaba and Mexico, Pinpin became a visita of Arayat in 1598. It was renamed as Sta. Ana, and in 1756, became an independent parish. It was only 23 February 1760 that a prior, Fr. Lorenzo Guevarra OSA, was assigned to Sta. Ana. He was assisted by Fr. Alonso Forrero, who baptized Vicente de Guevarra, the first entry in the libros bautismos dated 1760.

In 1853, the foundation of the present church was begun by Fr. Ferrer. Of stone and bricks, the church was eventually finished by Fr. Lucas Gonzales, who also added, in 1857, the magnificent hexagonal 5-storey canopied belfry, topped by a dome with a cross. The funds for the materials were raised by the people of Sta. Ana which were sourced from different parts of Luzon. The stones came from Meycauayan, Bulacan while wood was sourced from the forests of Porac and Betis. In all, the cost of the building was an astounding 5,568 Pesos and 25 reales.

The church, in the succeeding years was expanded to include a stone convento, built by Fr. Antonio Redondo in 1866. For five years, beginning 1872, the church was refurbished by Fr. Francisco Diaz and Paulino Fernandez. Fr. Felixberto Lozano constructed the fence in the mid 1930s, while Fr. Osmundo Calilung elevated the flooring of the altar during his term (1946-49). From 1955-1956, Fr. Francisco Cancio had the ceiling repaired and the bell tower given a fresh palitada.

Historian Mariano V. Henson recorded five bells in the campanera: Ntra. Sra. Del la Paz, dated 1879 and cast by Hilarion Sunico, was donated by Don Jose Revelino during the term of Fr. Paulino Fernandez. The biggest bell is dated 1857. All other bells inscribed with the names of Ntra. Sra. De la Correa, San Agustin and Sta. Ana, were donated by the town principalia at various years during the 1870s.

The interior of the church of Sta. Ana has been updated many times. The image of the town’s titular patroness, Santa Ana, appears with the young Virgin Mary in the central niche of the retablo mayor. Smaller altars hold vintage images. A relic of Santa Ana is also housed in the church.

Sunday, May 15, 2011

*249. THE REDEMPTION OF FR. JOSE C. DAYRIT

ONCE A PRIEST. Fr. Jose Dayrit left the priesthood to marry and raise a family, leaving his Kapampangan community in turmoil. He became a researcher and a college dean after turning his back on his profession. This picture is from his Sapangbato days where he served as a chaplain. Ca. 1936.

ONCE A PRIEST. Fr. Jose Dayrit left the priesthood to marry and raise a family, leaving his Kapampangan community in turmoil. He became a researcher and a college dean after turning his back on his profession. This picture is from his Sapangbato days where he served as a chaplain. Ca. 1936.The post-religious life of Fr. Jose Cunanan Dayrit is no different to the experience of many former priests who left their holy vocations and struggled to get back into mainstream society. While there are many reasons for leaving priesthood—disillusionment, internal squabbles, inability to live by the rules, human frailty (especially when it comes to matters of the heart), such rude awakenings are often met with disapproval by a harsh and judgmental community, leaving former priests stigmatized as they try to fit back in.

Jose was born on 12 September 1908, the youngest son of Eligio Dayrit and Eduviges Cunanan. The Dayrits were an enterprising family—Eligio’s brother, Felipe, was the first pharmaceutical chemist of Mabalacat town. Jose shared this brilliance, and after finishing his early studies in the local schools, he heard his religious calling. A month before turning 15, Jose entered San Jose Seminary on 12 August 1923. As a seminarian, he excelled in his studies and became a full-fledged priest on 5 April 1935, earning the distinction as the first ordained priest from Mabalacat.

Fr. Dayrit was first assigned to Sapang Bato, which was close by the military camp and which already had a thriving populace. He served the Holy Cross Parish from 1936-41. For convenience, he was likewise assigned as a chaplain of Fort Stotsenburg. He next move to the Immaculate Conception Church in Guagua, where he finished a one year term (1938-39). Even if his stay in the parish was only for a short span of time he was also well loved because he was regarded as a kind and good priest.

In 1937, Fr. Dayrit’s shining moment happened in that 33rd International Eucharistic Congress held in Manila—a first for Asia. The more popular events were the Philippine sectional meetings officiated by regional leaders. The meetings for Pampanga delegates were conducted at the San Agustin Church in Intramuros, and Fr. Jose C. Dayrit of Sapangbato was chosen as one of the speakers during the 2-day gathering together with Rev. Frs. Jose Pamintuan (Sampaloc) , Cosme Bituin (Guagua), Vicente de la Cruz (Mexico) and Esteban David (Minalin)

But alas, a bitter feud with his Bishop ensued—a disagreement that must have been so painful and profound so as to cause him to resign from priesthood. Fr. Dayrit found himself fallen from grace, so he retreated to Manila and never looked back, to pick up the pieces of a shattered life and start anew.

Calling on his entrepreneurial skills, he opened and operated Malayan Restaurant on busy Raon St. (now Gonzalo Puyat St.) near Avenida. It was while working here that he met Maria Paras, a kabalen from Angeles. After a short courtship, Fr. Jose Dayrit married Maria who gave him three children.

Fortune dealt him a cruel blow as the children came one by one. His food business was not enough to support his family though. He accepted a job at the Southern Luzon Colleges in Naga City and became the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. There, his new-found career blossomed, and he put to good use his gift of language (he knew Latin, Greek and Spanish) by translating Jose Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere into Kapampangan (“E Mu Ku Tagkilan”). For the rest of his life, he would embark on exhaustive researches at the National Library and continued his passion for writing.

When Fr. Jose Dayrit finally died in the 60s, he was almost ignored by his town—only a handful attended his wake held at Our Lady of Grace, the main church of Mabalacat. But surely, that would not have mattered to him; it is the triumph of the human spirit despite adversities that will long be remembered and rewarded not by Man but by His Maker.

Thursday, April 7, 2011

*243. Rev. Msgr. GUIDO J. ALIWALAS, Missionary from the Mount

GUIDED BY HIS LIGHT. The very accomplished man of the cloth from Arayat, Rev. Msgr. Guido J. Aliwalas, enjoyed a long career in his chosen vocation, and was very involved in the affairs of the province--including a recall move against Among Ed Panlilio. Ca. 1950s.

GUIDED BY HIS LIGHT. The very accomplished man of the cloth from Arayat, Rev. Msgr. Guido J. Aliwalas, enjoyed a long career in his chosen vocation, and was very involved in the affairs of the province--including a recall move against Among Ed Panlilio. Ca. 1950s.Before his death on 25 May 2009, Rev. Monsignor Guido Jurado Aliwalas was one of the oldest living priests of Pampanga. He was born in Arayat town on 12 September 1916. After studying in the local schools, the young Guido answered his calling to be a priest and enrolled at the San Carlos Seminary. He was ordained on 29 June 1940, at the age of 24.

Fr. Aliwalas held a number of assignments, including Arayat, his native town. He is credited with advancing the cause of Marian devotion with the organization of the Legion of Mary in 1941. In fact, in the propagation of the Cruzada de Caridad y Buena Voluntad of thee lo Virgen de los Remedios that was conceived in the early 50s, it was Fr. Aliwalas and Fr. Quirino Canilao who fixed the schedule of the pilgrim visits of Pampanga’s patroness to different towns and barangays.

He was assigned in Minalin parish from 1958 to 1974, serving the town for 16 long years. He also became a member of the Knights of Columbus. In his senior years, he was an active campaigner of Our Lady of the Assumption Campus Ministry. The only controversial stand he took was when he joined 17 priest members of the Pampanga Prayer Warriors to support the recall move against the priest-governor of Pampanga, Ed “Among” Panlilio, in September 2008.

He lived in retirement for the rest of his life in Domus Pastorum, a home for priest at SACOP, Maimpis Village in San Fernando. His 2009 memorial homecoming was held at St. Catherine Parish in Arayat, where he was laid to rest at the Aliwalas Family Museum.

Sunday, January 30, 2011

*235. Father to the Lost and the Lonely: Rev. Msgr. BENEDICTO J.E. ARROYO

HE WHO COMES IN THE NAME OF THE LORD. The young Candaba-born Benedicto Arroyo as a high school graduate, age 17 . Future chaplain of the National Bilibid Prison and National Mental Hospital. Ca. 1934.

HE WHO COMES IN THE NAME OF THE LORD. The young Candaba-born Benedicto Arroyo as a high school graduate, age 17 . Future chaplain of the National Bilibid Prison and National Mental Hospital. Ca. 1934.I remember seeing Msgr. Benedicto Arroyo at the Cardinal Santos Memorial Hospital sometime in 2004 when I visited a sick aunt. I was with my Del Rosario-Tinio relatives when we chanced upon him in the elevator. The Tinios were related to him by marriage and an uncle-priest, Msgr. Manuel del Rosario, who was a dear friend of his.

In his 80s, the portly father was still at it, in a hospital, no less, ministering to the infirmed and the sick, a calling that he embraced, and which would become the hallmark of his long career as a Filipino religious.

The good monsignor was born in Candaba on 16 August 1917, the fifth child of Dr. Esteban Sadie Arroyo and Adela G. Evangelista. His father was a University of Sto. Tomas medical graduate and he was, at one time, the presidente municipal of Candaba and a co-founder of the Arayat Sugar Central. The large Arroyo brood would grow to twelve children; aside from Benedicto, his siblings included Eduardo, Juan, William, Elena, Caridad, Socrates, Didimo, Sosimo, Aquiles, Africa and Pomposo.

Just like his brothers and sisters, Benedicto attended his primary grades at the local Candaba Elementary School. Bent on pursuing his religious vocation, he entered the San Carlos Seminary for his secondary education, and, upon completion, enrolled at the San Jose Seminary at age 17. He finsihed his priesthood at the height of the war on 20 March 1943, with the Most Rev. Michael Dougherty D.D. as his ordaining prelate.

His first assignment was as Assistant Parish Priest at Guiguinto, Bulacan (1943-46), and after which he was stationed at Tarlac, Tarlac for a year (1946-47). His next post was at the St. John the Baptist Parish in Pinaglabanan, San Juan (1947-55). The next two years of his religious life were spent ministering to the mentally sick, the physically infirmed and hardened criminals as Chaplain of the National Mental Hospital, National Orthopedic Hospital, and New Bilibid Prison, Muntinlupa.

Fr. Arroyo would prove his mettle during his term as an NBP chaplain. He celebrated Masses, heard inmates’ confessions and celebrated Christmas with his wards. He looked after the spiritual welfare of the inmates, firm in his belief that, like the parable of the prodigal son, they, too, are capable of finding their way back to God. So well-loved and effective was he, that he was promoted to Chief Chaplain and became a Penal Catholic Chaplain Coordinator in 1962. He likewise became a member of the Board of Pardon and Parole and headed the Classification Board of the National Bilibid Prison as its Chairman.

Fr. Arroyo would eventually be assigned to the Parish of San Rafael in Pasay City and become a Vicar Forane of the Vicariate of St. Raphael. Despite his many functions, he found time to become the Spiritual Director of the Maria Coronada movement as well as an esteemed member of the Archdiocesan Pastoral Council.

The monsignor also loved travelling, and his sojourns have taken him all over Europe and the United States where he has many relatives. He observed his Diamond Sacerdotal Jubilee in 2003 and spent his retirement years at Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary. Msgr. Benedicto J.E. Arroyo passed away on 21 September 2010 at the grand age of 93. He is interred at the Manila Memorial Park in Sucat, Parañaque.

Benedictus Qui Venit In Nomine Domini

(Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord)

Sunday, June 6, 2010

*198. SISTERS ACT

O SISTER, WHERE ART THOU? A cloistered nun is visited by relatives who could only peek through the wooden window slats for a few, precious minutes. They could not even touch her. Monastic rules were designed to be severe to test the faith, will and morale of religious people. But even life in the convent could not prevent early Kapampangan nuns from achieving their highest spiritual goals of serving man and God. Ca. 1920s.

O SISTER, WHERE ART THOU? A cloistered nun is visited by relatives who could only peek through the wooden window slats for a few, precious minutes. They could not even touch her. Monastic rules were designed to be severe to test the faith, will and morale of religious people. But even life in the convent could not prevent early Kapampangan nuns from achieving their highest spiritual goals of serving man and God. Ca. 1920s.Kapampangan men of cloth figured early in sowing the seeds of the Catholic faith in our Islands. The early Filipino members of the religious orders introduced in the Philippines were mostly Kapampangans: the 1st Filipino Jesuit (Martin Sancho, admitted to the novitiate in Rome in 1593), the 1st Recoleto (F. Juan de Sta. Maria Dimatulac of Macabebe, 1660). Pampanga’s revered pioneers also include the 1st Filipino priest ( P. Miguel de Morales, Bacolor, ordained in 1654) and the 1st Filipino Cardinal (Rufino Cardinal Santos, Guagua, elevated to cardinalship in 1960).

But the pious daughters of Pampanga were equally commendable in their quest to serve the will of their God; and it can be said that their was a more daunting task than the challenges faced by their male counterparts, as they had to over come overcome barriers like gender, class and racial prejudices before they could find their place in the Philippine church.

The first Filipino nun, for instance, Sor Martha de San Bernardo, a Kapampangan whose roots are no lost in history, had to make a great personal sacrifice to be admitted to the religious order of Poor Clares. The order, the first in Asia, had been founded by the Spanish Franciscan nun, Madre Jeronima de la Fuente (now Venerable) in 1621. It barred ‘indias’ like Martha, despite the backing of Spanish nuns who testified to her nobility and virtue. To skirt the Spanish laws that applied to the Philippine colony, Martha sailed for Macau, where, aboard the ship and far from Spanish domain, she was invested with the holy habit. She must have professed her vows in the monastery of the Poor Clares in Macau. Here--even after King Joao IV of Portugal ordered the expulsion of Spaniards in Macau as a result of Portugal’s secession from Spain in 1644-- Sor Martha would stay and serve the order for the rest of her life.

The Franciscan Provincial, after taking note of Sor Martha’s exemplary life and example, relaxed the rules for the next wave of Filipina applicants. Another Kapampangan member of the principalia was admitted to the mother house of the Poor Clares in Manila to become the second Filipino nun. Sor Madalena dela Concepcion received her habit from Abbess Madalena de Christo on 9 February 1636, and professed her monastic vows a year later. For 49 years, this Kapampangan nun led a humble life, performing difficult taskas and abhorring positions of honor until her death on 5 April 1685.

Two persevering sisters with clear Kapampangan roots would work against all odds to found a religious congregation which, in the the 21st century, would find worldwide recognition and acclaim. Dionisia Mitas Talangpaz de Santa Maria (1691-1732) and her younger sister, Cecilia Rosa de Jesus (1693-1731) were born in Calumpit, Bulacan but were half-Kapampangans owing to their paternal grandmother, Juana Mallari and maternal grandfather, Agustin Sonsong de Pamintuan, both from Macabebe. Pamintuan was revolutionary leader in the 1660 Pampango Revolt. Another notable kin is their great granduncle, the saintly Bro. Felipe Sonsong, a Jesuit and a martyr from the same Macabebe town.

The duo founded the Beaterio de San Sebastian de Calumpang in Manila in 1719, the only one founded by Indias among 4 Philippine beaterios (a Chinse mestiza, Mother Ignacia del Espiritu Santo founded the 1st beaterio in 1684, now known as the Religious of Virgin Mary). But they had to overcome great difficulties and oppositions posed by cynical Recollect authorities who stopped their screening of applicants, recalled their habits and expelled them from the convent grounds. Today, the Beaterio is known as the Congregation of Augustinian Recollects, the oldest non-contemplative religious community for women in the Augustinian Recollect Order throughout the world.

Coming from a patriotic and affluent family from Bacolor, Srta. Cristina Ventura Hocorma y Bautista, was born with a silver spoon in her mouth and could have chosen to live a life of ease. But she forsook all these to become a nun of the Hijas de la Caridad (Daughters of Charity) in 1872, only the 3rd Filipina to do so. Using her inherited wealth, she founded the Asilo de San Vicente, a school for underprivileged girls in Paco. She dedicated her lifetime teaching and serving the poor.

Many more holy women of Pampanga followed the path of these early trailblazers. Sor Bibiana Zapanta of Bacolor and a nun of the Beaterio de la Compañia was the 1st beata missionary to Mindanao. In 1875, she was assigned to the mission school in Tamontaca, Cotabato as a principal. Sor Josefa Estrada de San Rafael became the first Filipino Poor Clare in the 18th century. Descended from Lakandula and with roots in San Simon, Josefa or Pepita professed her vows in 1881. Beata missionaries to China included Sor Ana del Sagrado Corazon de Jesus and Sor Pascuala Biron del Sagrado Corazon de Jesus who founded the Asilo de la Sta. Infancia in Fijian.

The life stories and achievements of these nuns, sisters, beatas and mystics are incredible testaments to Kapampangan women power, providing inspiration to both the laity and Philippine clergy. Shoulder to shoulder, they stand as co-equals alongside the Kapampangan men who preceded them, in their unyielding pursuit to serve Man and God.

(Source: Laying the Foundations: Kapampangan Pioneers in the Philippine Church 1592-2001, by Dr. Luciano P.R. Santiago. Holy Angel University Press © 2002)

Sunday, May 2, 2010

*192. MSGR. JOSE R. DE LA CRUZ: Renaissance Man of the Cloth

FR. JOSE DE LA CRUZ, as a graduate of Sacred Theology of Santo Tomas University. Dated 1943.

FR. JOSE DE LA CRUZ, as a graduate of Sacred Theology of Santo Tomas University. Dated 1943.Recently, just a week after Good Friday 2010, Kapampangans mourned the loss of one of the most accomplished Kapampangan religious ever to come from the the province. Msgr. Jose Reyes de la Cruz passed away on 10 April 2010, almost month short of his 97th birthday. The good monsignor lived a long and full life, marked with brilliant career achievements not only as an extraordinary man of the cloth but also as a theologian, world traveler, literary and musical genius and a Catholic mass media practitioner.

The future monsignor was born in the sleepy barrio of San Matias, Guagua on 8 May 1913. His uncle, Fr. Vicente M. de la Cruz, was a well-known priest in Sta. Rita, and this must have also spurred him to answer his priestly calling. At age 15, he entered the San Jose Seminary as a high student and graduated as the class valedictorian. He continued to earn a Philosophy degree from the seminary and in just three years, graduated Summa Cum Laude.

The bright seminarian was sent to the International Gregorian University in Rome, but his frail health did not allow him to finish his studies there. He went back to the Philippines in 1937 and the following year, he enrolled at the Central Seminary of the University of Santo Tomas. In 1941, after graduating with a licentiate Summa Cum Laude, he was finally ordained as a priest. Two years later, he earned a doctorate degree in Sacred Theology, Magna Cum Laude. Not content with a doctorate, he also obtained a Bachelor of Laws from the pontifical university.

In the mid 40s, “Among Pepe” was assigned as the parish priest of Licab in Nueva Ecija. His other postings included San Marcelino in Zambales, Guagua and Bacolor. A seasoned global traveler, he has gone around the world 10 times, and has visited 37 countries in 18 separate trips. In Rome, he would act as a guide for visiting Filipino priests, often accommodating their requests for tours around the Vatican and its environs.

In 1952, he represented the Diocese of San Fernando in the International Conference of the Apostleship of Prayer and Nocturnal Adoration in Barcelona, Spain. In 1958, he attended the Centennial Celebration of the Lourdes apparition in France.

Back home, he helped in launching the crusade of Charity revolving around Virgen de los Remedios, the patroness of Pampanga. He anchored a radio program over DZPI Manila, using the show as channel for his catechism. He also became a columnist for several Catholic religious publications. Msgr. De la Cruz also served as the longtime parish priest of the Immaculate Conception Church of Guagua from 1957-1974, taking over Rev. Fr. Pedro Puno. While there, he livened up the local church scene by organizing the People’s Eucharistic League and activating the Cursillo Movement. He also improved the church, reconfiguring the altar area to make it circular, and adding on a golden monstrance to the church vessels, a precious find from is many travels.

In 1964, Among Pepe figured in a sensational criminal case in which 15 year old Corazon “Cosette” Tanjuaquio, daughter of a prominent Guagua family, was kidnapped for ransom. The perpetrators chose the priest to act as an emissary between them and the authorities. Several times, the courageous reverend volunteered to deliver the ransom money, often driving alone to the agreed-upon site, waiting long hours and even surviving a shooting attempt. The kidnappers were eventually apprehended.

A multi-dimensional Kapampangan, Among Pepe also dabbled in music and was adept in playing the violin. During his student days, he was named as the Orchestra Conductor of the San Jose Seminary and the Central Seminary of U.S.T. He was also an outstanding poet and prodigious writer, composing inspiring prayers in English, noted for their intuitive and vivid sensitivity. On 26 August 1969, Msgr. Dela Cruz delivered the invocation of the World Congress of Poets held in Manila.

In the 1980s, Msgr. De la Cruz continued to write religious features and columns while ably assisting Archbishop Oscar V. Cruz of the Archdiocese of San Fernando. His last assignment was at the St. Jude Thaddeus Parish in San Agustin, San Fernando. About 6 years ago, I had the opportunity to meet him in his St. Jude home. Though slowed down with age and needing assistance, his mind remained clear and alert, and he talked to us in a gentle, but commanding tone in impeccable English. In his little room, he sat and chatted with us, surrounded with mementos of his life—stacks and shelves of well-thumbed books, diplomas on the wall and his favorite violin.

Reflecting on his death, I am drawn once more to one prayer he wrote, one of the most lyrical, most touching ever composed:

“Lord, let me find you in the angelic smile of innocent children..

And in the measured pace of old age.

Let me hear you in the aged canticles of singing streams..

And in the soft murmur of evening breezes..

Lord, let me find you and hear you, everywhere I go

And at every moment of my waking hours,

For the whole universe is Your image and all good music s your singing voice..

This, my humble creator, is my humble prayer. AMEN.

In the bosom of his Lord, we will find the good monsignor again.

Thursday, January 28, 2010

*180. RECOLLECTIONS OF A CATECHISM CLASS

SPREADING THE WORD. Catechists of San Simon, Pampanga. With Fr. Francisco V. Cancio. Dated June 1949.

SPREADING THE WORD. Catechists of San Simon, Pampanga. With Fr. Francisco V. Cancio. Dated June 1949.I was in my Grade 4 or 5 class when the teaching of catechism was introduced to students of Mabalacat Elementary School. I remember they were held once a week, on Fridays, right after our regular classes. I would often fret whenever Fridays came, as it meant staying for another hour in the classroom, to be drilled by our catechism teacher—actually, a uniformed high school student from nearby Mabalacat Institute with religious medals on her lapel—about prayers, the Sacraments and lessons from the Bible. Since I already had a couple of children’s religious books, the smart-aleck in me thought that I was already familiar with her catechism material.

I distinctly recall our catechism teacher starting her lecture with a question: “What was the sin of Adam and Eve that caused them to be driven from Eden?”. Of course, I knew the answer—I raised my hand and answered with confidence: “They ate the forbidden fruit—the apple!”. To my shock, the teacher replied that I was wrong. “Pride!”, she said, “it was pride that caused their downfall. And it’s one of the 7 Deadly Sins”. Cowed by embarrassment, I silently took my seat. In the Fridays that followed, I listened more intently, and soon, I was taking my catechism lessons more seriously.

For many Filipino children living in the colonial times, the teaching of the basic tenets of Christianity began early, using the caton, a primer on the alphabet, common prayers and religious doctrines. Catons were loosely based on Doctrina Cristiana, the first book published in the Philippines by the Imprenta de los Dominicanos de Manila and approved as a catechetical guide during the 1782 Manila Synod, under Bishop Domingo de Salazar. Catons published in different Philippine dialects, including Kapampangan.

The establishment of a formal system of education paved the way for the inclusion of catechism instruction in schools, particularly those founded by religious groups. The laity, encouraged and supported by their priests and parishes, took on the teaching of catechism in community schools as their apostolate, becoming an important force in the Church, especially from the 1930s through the post-war years.

This led to the publishing of catechism manuals, and one in Kapampangan, “Ing Canacung Catecismo”, was printed in 1938, a translation of an existing English version, “My Catechism”, by Rev. Fr. Vicente M. de la Cruz. The aims of the catechism books was outlined on the preface: “..macapariquil ya caring aduang tapuc a anac: muna, caretang arapat dane ing Mumunang Pamaquinabang iñang anac lapa, banrang ñgeni isundu at ganapanan ing pamagaral da qñg religion; at cadua, caretang aliua, bistat maragul nala, ditac lapa cabaluan qñg casalpantayanan, balang magsadia qñg carelang Mumunang Pamaquinabang” (the book is meant first, for children who have received their First Communion, so that they can continue their study of religion; and second, older ones who grew up knowing little knowledge of their faith, so they can be prepared for their First Communion).

Catechism instruction manuals followed the same structure—starting with a chapter-by-chapter presentation of the basic teachings (“Ing Dios, Miglalang Ampon Guinu”, “Ding Atlung Personas Qñg Dios, Ing Tanda ning Cruz”/ God, Our Lord and Creator, The Three Persons in God/ The Sign of the Cross, etc.), followed by a series of drill questions, with matching answers ( Q. Nanung pengacu ning Dios daptan, banacatang panuanan carin banua? A. Ing Dios peñgacu neng itubud quecatamu ing metung a Mañaclung / Q. What did God promise to do, so we can enter Heaven? A. God promised to send a Savior).

The teaching of religion as a separate subject was a requisite in the curriculum of every Christian school. To stress the importance, “Best in Religion” awards were given and held as much weight as a “Best in English” and “Best in Math” awards. Despite my assiduous studies, I never got that medal. But I did get to master my prayers: Ibpa Mi, Ing Bapu Maria, Ligaya King Ibpa, Bapu Reyna as well as recite the Rosary with its misterios, Apulung Utus ning Dios and Pitong Sakramento. In the end, by taking to heart the teachings of the Catholic Church, I was one step closer to Heaven, and in the mind of a 10 year old boy, I felt that was the better reward.

Monday, March 30, 2009

*137. BLESSED BE GOD: The Religious of Betis

SEMINARISTAS DE PAMPANGA. A group of Kapampangan seminarinas from San Carlos Seminary pose for a souvenir picture. Future priests Andres Bituin (1st person on top row) and Felipe Roque (4th from right, 2nd row) are from Betis.

SEMINARISTAS DE PAMPANGA. A group of Kapampangan seminarinas from San Carlos Seminary pose for a souvenir picture. Future priests Andres Bituin (1st person on top row) and Felipe Roque (4th from right, 2nd row) are from Betis.The people of Betis have always been proud of their town’s reputation of having produced the most number of Catholic priests than any Kapampangan town. Betis, in Guagua town, has been described by Bishop Emilio Cinense as “a model parish, a truly Christian parish, a peaceful place to live in..”, a bedrock of Christianity as evidenced by the intense religiosity of its residents, then and now.

Among the first Filipino founders of capellanias (pious trust funds) in 17th century Philippines were Don Pedro Lumalong, Juan Panganiban, Francisco Gutierrez, Martin Tandang, Dna. Francisca Biguiad, Geronima Matig, Cathalina Lindon, Ines Julir and Isabel Taolaya—all from Betis. The perpetual grant was usually in the form of agricultural lands, the income of which was used to support a priest (capellan, or chaplain), who, in turn, was mandated to offer Mass for the soul or intention of the founder.

Also a resident of Betis is Don Macario Pangilinan (1800-1850), who is credited with translating the Tagalog version of Via Crucis into Kapampangan: “Ing Dalan a liualana ning Guinutang Jesucristo quing pamamusana quing mal a Santa Cruz”. The Archbishop of Manila, F. Jose Segui, granted an indulgence of 80 days to those who would pray it.

The first Filipino Doctor of Theology also is an accomplished Betiseño—Dr. Don Manuel Francisco Tubil (b. 17 June 1742/d.6 Sept. 1805). He earned his doctorate from the University of Santo Tomas in 1772. He eventually became a priest in 1770, and rose up the ranks of the church hierarchy, an accompished Indio among Spanish religious leaders.

A 1959 listing of the sons and daughters of Betis who chose religious vocations include the following:

1. Rt. Rev. Msgr. Cosme P. Bituin D.P. (1929 Parish priest Angeles, Bacolor)

3. Rt. Rev. Msgr. Andres Bituin D.P. (1920 Vicar Forane)

4. Very Rev. Msgr. Serafin Ocampo P.C. (1945 Diocesan Secretary of Lourdes, Angeles)

5. Very Rev. Roberto Roque (1916 Vicar Forane, San Ildefonso, Bulacan)

6. Very Rev. Felipe Roque (1920 Vicar Forane, Betis)

7. Rev. Jose Bondoc (1929 Parish priest, Candaba)

8. Rev. Genaro Sazon (1930 Parish priest, Porac)

9. Rev. Melencio Garcia (1936 Paish priest, Mexico)

10. Rev. Jacobo Soriano, (1936 Parish priest, Capas, Tarlac)

11. Rev. Bernardo Torres, (1916 Parish priest, San Rafael, Bulacan)

12. Rev. Florentino Guiao, (1938 Parish priest, Dinalupihan, Bataan)

13. Rev. Pedro Capati, (1939 Parish priest, San Rafael, Macabebe)

14. Rev. Hermogenes Coronel, (1930 Chaplain, Balayan, Batangas)

15. Rev. Pablo Songco, (1939 Parish priest, San Luis)

16. Rev. Francisco Mendoza, (1944 Seminary professor, Apalit)

17. Rev. Julian Roque, (1955 Parish priest, San Isidro, Guagua)

18. Rev. Norberto Coronel, (1947 Seminary professor, Apalit)

19. Rev. Alfonso Ducut, ( 1949 Parish priest, Anaw, Mexico)

20. Rev. Felipe Pangilinan, (1949 Parish priest, Mariveles, Bataan)

21. Rev. Victor Serrano, (1949 Parish priest, Maypajo, Caloocan)

22. Rev. Domingo Gullas, (1951 Parish priest, Laur, Nueva Ecija)

23. Rev. Fr. Gregorio Torres, (1951 Parish priest, Del Carmen)

24. Rev. Vicente Coronel, (1954 Asst. priest, Angeles)

25. Rev. Alejando Ocampo, (1954 Asst. priest, Betis)

26. Rev. Jose Guiao, (1955 Asst. priest, Macabebe)

27. Rev. Teodulfo Tantengco, (1956 Asst. priest, Arayat)

28. Sr. Rapahel de Jesus (Rosario Pangilinan), professed 1932

29. Sr. Celina de Marie (Asuncion Legion), professed 1949, St. Paul de Chartres, St. Paul College, Manila.

30. Sr. Jeanne Mary of the Holy Wounds (Ignacia Guanlao), prfessed 1953. Carmelite Discalced, Yule Island, Papua, Oceania, Australia

31. Sr. Cecilia S. Gozum, professed 1953, Religiosas Hiyajs de Jesus, Pototan, Iloilo.

All these Betis religious have apparently taken to heart their patron’s calling by following in his footsteps. After all, Santiago de Galicia, one of the 12 apostles, was also called by Jesus to preach the Gospel around the globe. With him as inspiration, these men and women of the cloth have stood fast in one spirit, with one mind, laboring together for the strengthening of Kapampangan faith and fidelity in the Lord. In Betis, many are called, and many are chosen.

Monday, December 8, 2008

*117. MOST REV. ALEJANDRO OLALIA D.D., 1st Archbishop of Lipa

BISHOP FROM BACOLOR. Most. Rev. Alejandro Olalia, Kapampangan. Bishop of Tuguegarao and the 1st Archbishop of Lipa, Batangas.

BISHOP FROM BACOLOR. Most. Rev. Alejandro Olalia, Kapampangan. Bishop of Tuguegarao and the 1st Archbishop of Lipa, Batangas.The Catholic Church hierarchy in the Philippines is peopled with many Kapampangan religious leaders who are noted for their pioneering spirit and missionary zeal. The first names that come to mind are Cardinal Rufino Santos of Guagua, the 1st Filipino prince of the Church and Archbishop Pedro Santos of Porac. But equally outstanding was the life of another Kapampangan priest who also rose to become an archbishop of note: Most Rev. Alejandro Olalia.

The future church leader was born on 26 February 1913 in the town of Bacolor. He studied at the Bacolor Public School and attended San Carlos Seminary (1930-36), from where he finished his priestly studies. Sent to the Gregorian University, he was ordained a priest at age 27 on 23 March 1940 at the Pio Latino American College. Two years later, he obtained a Licentiate in Canon Law. He then hied off to the United States as an exchange priest, where he served in a Georgian parish. On 18 May 1944, he earned a Doctorate in Canon Law from the Catholic University of America.

Upon his return to the Philippines on 4 February 1946, he was assigned to be the Assistant Parish Priest of Tondo. In September of 1947, Fr. Olalia was named as the private secretary of the Archbishop of Manila. His leadership qualities earned him an appointment as Coadjutor Bishop of Tuguegarao and Titular Bishop of Zela on 2 June 1949 at the age of 36. A scant two months after, he was ordained as bishop on 25 July 1949. The next year, he succeeded the Dutch-born Bishop Constancio Jurgens C.I.C.M., who served Tuguegarao for 22 long years.

From Tuguegarao, the bishop was assigned to Lipa in Batangas in 1953, replacing then Bishop Rufino J. Santos, who was elected as Archbishop of Manila. The reverend was noted for being a good manager of the church, often conducting business even in full Prelate regalia. He was also noted for being an open-minded religious, “who accepted all good things that came to the Philippines, including the Cursillo”. He was the first to support the SOS Children’s Village in Lipa, a haven for abandoned and orphaned children—a revolutionary concept at that time, established in Lipa in 1967.

It was during his term that the Diocese of Lipa became the tenth Archdiocese and Ecclesiastical Province as decreed by Pope Paul VI on 20 June 1972. He was likewise elevated to the rank of an Archbishop. Archbishop Olalia would stay at the diocese for 20 years, until his death on 2 Jan. 1973, not quite 60 years old.

(*NOTE: Feature titles with asterisks represent other writings of the author that appeared in other publications and are not included in the original book, "Views from the Pampang & Other Scenes")

Thursday, August 28, 2008

*102. YA ING PARI, YA ING ARI: The Priest Is King

AMONG US MEN. Kapampangan religious in the persons of Arch. Rufino Santos, Msgr. Cosme Bituin , Fr. Vicente Coronel, Fr. Manuel V. del Rosario are feted by the Del Rosario family of Angeles, headed by host Dr. Fernando Del Rosario. Early 60s.

AMONG US MEN. Kapampangan religious in the persons of Arch. Rufino Santos, Msgr. Cosme Bituin , Fr. Vicente Coronel, Fr. Manuel V. del Rosario are feted by the Del Rosario family of Angeles, headed by host Dr. Fernando Del Rosario. Early 60s.The Philippines—touted as Asia’s only Christian country—is running out of priests fast. Even in our very own province, our parishes are being left to aging priests way past their retirement years. As a result, the quality of their ministry have suffered and continue to deteriorate. Our good priests are humans after all, subject to natural frailities—mood swings, memory loss and the occasional hormonal imbalance. Talk about rambling sermons that go nowhere, mismanagement of church funds, hidden families, wealth accumulation sprees and grouchy temperaments.

This has led to ‘disgusto’ on the part of the parishioners sometimes, and I have heard of at least one story where church elders of one Pampanga parish tried to oust their indifferent priest through ‘people power’.

As a general rule though, we Kapampangans are a forgiving and understanding lot. We are long on tolerance, quick to kowtow before authorities. Thus, when it comes to our priests, we treat them consistently with our pampering, over-solicitous attitude. A Kapampangan hymn sung during Mass goes: “Balen a pari, balen a ari” (Town of priests, town of kings)—and this speaks true of the royal treatment we accord our religious leaders.

We call them “Among”—a derivative of the word “amo”, meaning Master or Lord—thus putting them in a class above us. We kiss his hands, we trail behind him when we walk and we give him money envelopes with his every visit. During fiestas, the best seat of the house is reserved for the priest. It is no wonder that, served with the richest, most delicious food, he fattens up—from his belly to his nape—leading to an expression called “katundun pari”, a bulging nape like a priest’s.

This extra reverence of Kapampangans to their parish priests can be traced back to the days when the Augustinian friar was looked at as the most powerful figure in town. It is this same attitude that our national hero, Jose Rizal, took note of and loathed, documenting these excesses in his novels.

On the other hand, there is basis for this unabashed attention given to priests. The early Augustinians assigned to Pampanga were noted for their rare virtues like compassion, humility and the will to serve. Several letters in the Augustinian archives reveal the sincere feelings of the Kapampangans towards their church leaders. Written by gobernadorcillos and local town people, these testimonial letters give us a glimpse of the heroism of early Augustinian priests.

In a letter dated 11 December 1897 sent by the Angeles principalia to the Augustinian Provincial requesting him not to transfer their cura, Fray Rufino Santos, the people wrote: Fr. Santos is a kind priest, a good father, the best advser and assiduous protector. To him, Fr. Provincial, we owe our peace in these (critical) times..”.

Floridablancans also asked for a permanent stay for their parish priest Fray Pedro Diez Ubierna in an 1898 missive: “ During the ill-fated days of such disastrous Revolution..our Rev. Parish Priest protected us, who, like Providence, arrived in time to be our venerable Pastor. With his affable treatment and talent, he knew how to inculcate in the hearts of all his faithful, the humility and true obedience to the Divine Laws, strengthening us with the Word of the Gospel and setting good examples, which he so eloquently knows how to transmit in the local language”.

Returning friars assigned to Pampanga spoke glowingly of the renown hospitality of Kapampangans, news that reached even the Augustinian Royal College in Valladolid, Spain. In the years that followed, this same indulgent regard was transferred to native priests, and to this day, this attitude persists, notwithstanding conduct unbecoming. The dwindling number of priestly vocations have also given the Christian populace not much choice but to accept whoever is assigned to their parish, warts and all. As one parishioner moaned, “ala tang agawa, ditak na la reng mag-pari” (‘we can’t do anything, only a few are entering priesthood).

With that tone of fatal resignation, we might as well rephrase that familiar line: “Ya ing pari, ya ing ari…itamu ing mayayari!” (He is the priest, he is the King…but we are the victims).

Monday, June 23, 2008

*89. In the Footsteps of a Saint: FR. JUAN PEREZ DE STA. LUCIA.

A HEART FOR HEATHENS. Fr. Perez de Sta. Lucia labored amongst the lowly Negritos, protecting them from Spanish exploitation and even joined them in jail when some aborigines were falsely accused of hiding contraband goods. Photo from the Recollect A rchives, courtesy of Fr. Rommel OAR.

A HEART FOR HEATHENS. Fr. Perez de Sta. Lucia labored amongst the lowly Negritos, protecting them from Spanish exploitation and even joined them in jail when some aborigines were falsely accused of hiding contraband goods. Photo from the Recollect A rchives, courtesy of Fr. Rommel OAR.Among the Recollects and Tarlaqueños, there is a future saint being talked about who served the town of Capas with extraordinary devotion and grace. Above all, he dedicated most of his missionary life improving the lot of Aetas by creating the mission center of Patling just for them, to facilitate their integration to Christian society. His name is Fray Juan Perez de Santa Lucia, who, at one point, also served Mabalacat town as a companero of Fr. Jose Varela Fernandez de la Consolacion.

Born to Felipe Perez and Juliana de Lucio on 8 February 1817 in Santander, Spain, Fr. Juan joined the Recollect order in 1843, choosing for his patron, Santa Lucia. Arriving in Manila as a member of a mission group on 22 July 1843, he was ordained here in December of the same year. Mabalacat was his next stop, where, on 23 February 1844, he joined Fr. Varela as an assistant. Here, he quickly immersed himself in learning the Kapampangan and Zambal languages. He stayed on in Mabalacat until September 1845, because by the 2nd week of the same month, he was named as missionary of Capas, which was then still a part of Pampanga.

It is in Capas where he truly left his mark, working with indefatigable zeal and fervor among his parishioners. For instance, when water from Mt. Pinatubo inundated Capas in May 1850, he stayed with his parishioners, leading them to higher grounds, unmindful of his own safety. He wisely made use of donations to build a stone church for Capas.

Beyond Capas, he also worked tirelessly among the Aetas in Patling, protecting them from the exploitation of Spaniards and settlers hungry for new lands. So detached was he from materialism that when his Father Provincial gifted him with clothing, he tore the fabric into smaller pieces which he then gave away to the Aetas. In yet another instance, when several Aetas were jailed by the police for allegedly hiding contraband merchandise, the good father joined them in jail! Not even the governor of Pampanga, Don Jose Paez, could make him move out of the prison.

In 1864, a great cholera epidemic hit Capas, and a large number of the population fell victim to the plague. Fr. Juan labored day in and out to minister to the spiritual needs of the dead and dying. Sadly, he too was afflicted by the same disease. This holy man who started his walk to sainthood in Mabalacat, breathed his last on 20 June 1864, in his beloved Capas mission.

(Adapted from Dr. Lino L. Dizon, “Fr. Juan Perez de Santa Lucia, OAR: A Forgotten Saint?”, Kapampangan K Magazine Issue 6, pp. 27-29.)

Tuesday, February 5, 2008

70. PADRE MANING: The Life and Times of a Kapampangan Religious

KAPAMPANGAN MAN OF CLOTH. Fr. Manuel del Rosario y Valdez (1912-1987), age 27, shown as a young priest in his souvenir ordination picture, shortly after finishing his studies at the San Carlos Seminary. He was ordained by Manila Archbishop Michael O’Doherty. Ca. 1939.

KAPAMPANGAN MAN OF CLOTH. Fr. Manuel del Rosario y Valdez (1912-1987), age 27, shown as a young priest in his souvenir ordination picture, shortly after finishing his studies at the San Carlos Seminary. He was ordained by Manila Archbishop Michael O’Doherty. Ca. 1939. THE CARDINAL & THE MONSIGNOR AT CLARK. Fr, Maning was a constant companion of Rufino Cardinal Santos. Sandwiched between 2 unidentified Clark Field officials are L-R: Fr, Alejandro Olalia (future Bishop of Tuguegarao), Cardinal Santos and Fr. Manuel del Rosario who are all Kapampangans Circa 1950s.

THE CARDINAL & THE MONSIGNOR AT CLARK. Fr, Maning was a constant companion of Rufino Cardinal Santos. Sandwiched between 2 unidentified Clark Field officials are L-R: Fr, Alejandro Olalia (future Bishop of Tuguegarao), Cardinal Santos and Fr. Manuel del Rosario who are all Kapampangans Circa 1950s.In my case, he was a surrogate father for 2 years, and a very strict one at that. The daily use of the bathroom was limited to 10 minutes max--or else he would pound the door till we came out. Curfew was set at 10:00 p.m., after which the iron gates to the rectory were locked. Many times, I would scale the gates to get in because my graduate classes would end past that time. Inside the rectory, wearing sandos was a no-no. Oh, how I would try getting out of his way, but then I had to assist him in his daily Masses and help out in different church duties so there was no escaping his temper. Then again, it was Tatang Maning who provided us 100% support as we struggled to eke out a living in Manila, giving free shelter and food, supplementing our meager salaries with additional allowances and treating us out to fancy dinners when we needed a break from our usual pork and beans meals. When we got homesick, it was Tatang Maning who amused and entertained us, taking us out in his car for a quick spin around the city.

As a child, I knew early that Tatang Maning--from the way he was held in high esteem by my mother, aunts and uncles--was kind of special, extraordinary even. At the peak of his priestly career, Tatng Maning rubbed elbows with the rich, the influential and the famous. I have seen his albums with photos of him chummy-chummy with Pres. Diosdado Macapagal, having lunches with former First Lady Trining Roxas, opera star Conching Rosal, Ambassador Rogelio de la Rosa, diplomat Mel Mutuc and joining Cardinal Rufino J. Santos in his many travels abroad. This, indeed, was a far cry from his very humble beginnings as the 8th child of Emilio del Rosario and Josefa Valdez, in a family that would soon grow to include 19 more children!

Born on 4 July 1912, the young Maning spent his elementary days at the San Fernando Elementary School. He then took his secondary education at the Pampanga High School, graduating in 1927. Two years later, in June 1929, he entered the San Carlos Seminary. Because the family was financially challenged (his other brothers were also taking expensive courses in Medicine, Law, Dentistry and Accountancy all at the same time), it took 10 years for him to be ordained. No less than the Most Rev.Msgr. Michael O’Doherty ordained him to sacred priesthood on 26 March 1939 at the Manila Cathedral. His first assignment was as a co-adjutor of San Juan del Monte and as Chaplain of the National Mental Hospital. In October 1939, he was sent back to his home province, serving briefly as a co-adjutor in San Fernando, before being assigned in 1940 to the parishes of Balanga and then Orion, Bataan as assistant priest.

In October 1941, he was finally named as the cura parocco of Zaragosa, Nueva Ecija. My then 13-year old mother kept him company there, and she would recount how Tatang Maning would negotiate the dirt roads on horseback just to reach out to his parishioners! His efforts were rewarded 6 years later with his appointment as Sub-secretary of Finance at the Arzobispado de Manila. Concurrently, he was also the Chaplain of the La Loma Cemetery.

Finally, on 15 May 1951, Tatang Maning was installed as the parish priest of San Roque Parish where he would stay on for the next 3 decades of his life. His first task was the renovation of the church, completing the project in 1952. In the next few years, he extended the church to include a rectory and a social hall. He was also instrumental in the erection of two barrio chapels in Obrero and Manuguit in 1963-64.

When Kapampangan Diosdado P. Macapagal ascended the presidency, Tatang Maning became his Spiritual Director. Likewise, he struck a deep friendship with fellow Kapampangan Cardinal Rufino J. Santos, often traveling to Europe together. When Cardinal Santos was elevated to the rank of a Cardinal in 1960, Tatang Maning was part of his entourage to Rome. In 19 April 1960, he was accorded the distinction of being named Privy Chamberlain of his Holiness, Pope John XXIII. Three years later, he was again named as Privy Chamberlain of His Holiness, Pope Paul VI. In 26 March 1964, he celebrated his Sacerdotal Silver Jubilee with a Testimonial Dinner given in his honor at the Winter Garden, Manila Hotel, an affair attended by no less than President Macapagal and the First Lady, Eva Macapagal.

Long after I have flown the Blumentritt coop and established my independence, I would still occasionally see Tatang Maning in his regular visits to Pampanga where he would make the rounds of the residences of his brothers and sisters where most are settled. By then, he was already retired, living with Imang Susing, another half-sister, in his spacious Marikina house, together with his beloved canines and a menagerie of exotic animals. Already in frail health, Tatang Maning passed away of emphysema on 25 Sept. 1987 at the Cardinal Santos Hospital. His remains were brought back to the San Roque Parish where his longtime parishioners paid their last respects.

Sometimes, when I pass by Blumentritt and see the church and its familiar grounds, I still think wistfully of Tatang Maning, my uncle priest, hoping to see a vision of him saying Mass, back hunched before the altar. I know a part of him still dwells there, in that busy Church which he loved best, where he touched the lives of thousands of people---wayfarers, devout women, beggars and vendors, babies, little children who had received the Holy Host from his hands, heroic sufferers, kindred spirits, sinners and souls unknown to him---living his Faith to the fullest in the service of the Lord.

(18 October 2003)

Monday, January 14, 2008

67. Pampanga's Churches: STA. MONICA CHURCH, MINALIN

SANTA MONICA CHURCH OF MINALIN. The ancient brickstone church with its impressive retablo-like façade has been standing witness for centuries to Minalin’s storied past. Here, a funeral procession is about to start. Ca. late 1950s.

SANTA MONICA CHURCH OF MINALIN. The ancient brickstone church with its impressive retablo-like façade has been standing witness for centuries to Minalin’s storied past. Here, a funeral procession is about to start. Ca. late 1950s.One other version though tells of a Malayan settlement headed by Kahn Bulaun, a descendant of Prince Balagtas. The place they say was famed for its beautiful women and when the Spaniards came, they described the town as “mina linda de las mujerers”. Subsequently, Chinese traders who frequented the place abbreviated the description to “Minalin”.

Minalin, as a place, was already in existence as a visita of Macabebe, as early as 1614. It was detached from its matrix in the same year but it was only in 1618 that a regular priest, P. Miguel de Saldana, was assigned to Minalin. On 31 October 1624, the parish was accepted as a vicariate with P. Martin Vargas as vicar prior. Sta. Maria, its pioneer barangay, was formed from an area of land that was ceded by the Datu of Macabebe to settlers Mendiola, Nucum, Lopez and Intal in 1638. It was named after the settlers’ wives, who were all named Maria.

There are no records as to who built the church, although it has been attributed to the work of P. Manuel Franco Tubil in 1764. One documented source cites the church’s completion before 1834. It was reconstructed at various stages: in 1854, 1877 (by P. Isidro Bernardo), 1885 and 1895 (repaired by P. Galo de la Fuente and Vicente Ruiz, respectively). The church, with Santa Monica as its titular patron (Feast Day, May 11) is 52 meters long, 13 meters wide and 11 meters high. The last Augustinian fraile to serve Minalin was P. Faustino Diez and the 1st native priest was P. Macario Panlilio.

The most notable architectural feature of the Santa Monica Church is its retablo-like façade. The main entrance and windows are bordered with a floral décor evocative of early folk altars. Corinthian columns act as support to the triangular pediment that is topped with a lantern-like kampanilya. In the early days, a lighted beacon was placed on top of the apex of the pediment to guide fishermen as they made their way from the river to the town. The structure is further complemented with a short row of balusters. The semi-circular niches hold painted stone statues of various Augustinian saints, and these are harmoniously designed to blend with the rose windows.

Flanking the church are two hexagonal 4 storey bell towers, a little squatty and low, yet solidly built. There are 4 century-old bells, dated from 1850 to 1877, dedicated to San Agustin and Sta. Monica. A low stone atrium with rare capilla posas encloses the convento. The Sta. Monica Church of Minalin stands as another sublime example of Pampanga’s religious heritage.

(27 September 2003)

Tuesday, January 1, 2008

65. THE OTHER MURDERS IN THE CLOISTERS

MABALACAT’S OTHER MARTYR: Fr. Victor Baltanas OAR (1869-1909), was briefly assigned to Mabalacat, assisting Fr. Bueno in his ministerial duties before he met his untimely death in Escalante, Negros. Another compañero, Fr. Juan Herrero, was earlier killed in Cavite. Source: Boletin de la Provincia de San Nicolas & The Augustinian Recollects in the Philippines, by Emmanuel Luis A. Romanillos.

MABALACAT’S OTHER MARTYR: Fr. Victor Baltanas OAR (1869-1909), was briefly assigned to Mabalacat, assisting Fr. Bueno in his ministerial duties before he met his untimely death in Escalante, Negros. Another compañero, Fr. Juan Herrero, was earlier killed in Cavite. Source: Boletin de la Provincia de San Nicolas & The Augustinian Recollects in the Philippines, by Emmanuel Luis A. Romanillos.Fr. Juan Herrero was Fr. Bueno’s compañero for just a period of 5 months in 1885. From Mabalacat, he was sent off to Cavite where he became the manager of “Compania Fomento de La Agricultura”. He, together with 9 other Recollect friars, were holed up in Imus, Cavite where they were shot to death by passionate Revolutionists.

The other unfortunate victim was Fr. Victor Baltanas de la Virgen del Rosario . Fr. Baltanas was born on 17 November 1869 in Berceo, La Rioja Spain. After becoming a Recoleto on 24 October 1886, he left on board the steamer Isla de Panay, and sailed to Barcelona. He continued his journey to the Philippines, arriving in Manila on 21 October 1891. No sooner had he unpacked when he was assigned to Mabalacat in late October 1891.

He was sent to Mabalacat as a young deacon to learn, strangely enough, Tagalog basics. Indeed, an examination of extant canonical books confirmed his presence in the town, assisting Fr. Bueno in his daily ministerial grind —from administering holy oils and chrisms to performing sacramental rites. His assignment was not permanent though, and he was shuffled from Mabalacat to Manila (where he received the Holy Order of presbyterate in 1892), Palawan (1894-1895), San Nicolas priory in Intramuros (1899-1902), back to Taytay, Palawan and then finally to Valencia, Negros Oriental where he served as assistant priest to Fr. Eusebio Valderrama. Finally, in October 1907, he became the parish curate of the Roman Catholic Church of Escalante town.

It was here in Escalante town that he was hacked to death in the head by an Aglipayan assassin, Mauricio Gamao, on the night of 15 May 1909, succumbing to his wounds the next day. The murder, motivated by the schism between Aglipayans and the Roman Catholic Church involving church property, was planned in connivance with the town head, Gil Gamao—Mauricio’s relative, who was subsequently convicted by Albert E. McCabe, an American judge of the Court of the First Instance, after a 3-month trial in Bacolod. Mauricio Gamao, as well as his cohort Gil Gamao, were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Fr. Baltanas died a martyr of the faith. Fr. Francisco E. Echanojauregui, parish priest of San Carlos who immediately attended to his dead fellow Recoleto in Escalante, described him in a 1909 letter to the vicar provincial: “Americans, Spaniards and Filipinos all assure me that he was an authentic priest, a zealous curate with unblemished repute…Everyone attests to me that Fr. Victor was incapable of raising his voice, not even to his boy-servant...his life was well ordered like that of a convent..This is to say he was an excellent person, as an individual, as a parish priest and as a friar”.

The martyr of Escalante was interred in San Carlos, but his bones were exhumed in 1995 due to acts of vandalism and robbery in the cemetery. These were then kept at the Colegio de Santo Tomas-Recoletos.

Two Mabalacat frailes—Fr. Juan Herrero and Fr. Victor Baltanas thus shared the same sad fate as their superior, Fr. Gregorio Bueno, meeting their hapless deaths in the hands of Filipinos in an uncanny parallel manner-- all happening in the heat of the Revolution and a religious schism, and with influential families involved.

(13 September 2003)

Wednesday, December 19, 2007

64. Murder Most Foul: THE CURSE OF P. GREGORIO BUENO

CURSE & CONSEQUENCE: Is this Mabalacat’s Fr. Bueno? This faded portrait, obtained from an antique dealer, shows a portly friar in Recoleto habit. At back is scrawled in pencil, “P. Gregorio Bueno.” Circa 1890.