TAKING CENTER STAGE. Compania Crispelita actors and singers set the mood for their performance with a rousing song number for the barrio audience of Lanang, Candaba. 1957.

Candaba, one of Pampanga’s ancient towns, represent the lowest point of Central Luzon. It is also a good distance away from the capital and commercial cities of San Fernando and Angeles, and from the 1930s to as recent as the 1950s, the town remained far removed from other Pampanga communities. Trips to Candaba were compounded by its marshy terrain, floods and the presence of Huk lairs in the area which made travelling difficult and hazardous.

Candabaweños, despite this isolation, looked to the occasional fiestas for entertainment, as movies could only be watched in distant urban towns. In some places, the only tenuous link which they have with the stage is the obsolete moro-moro and the dying zarzuela. On this account, artistic and enterprising locals started putting up dramatic troupes, beginning in in the 1920s and which flourished till the post-war years.

These theatrical groups or companies, went from barrio to barrio to show off their wares, a motley group of actors, musicians, directors, designers and technicians, to stage plays on makeshift stages before enraptured village crowds.

One of the earliest groups, was the Compania Ocampo, organized in 1923 by Isaac C. Gomez and Doña Concepcion Ocampo y Limjuco of Candaba. Gomez, a prolific poet who even competed against Crissot, wrote his 5-act opus, “Sampagang Asahar”which dealt with the prevailing tenancy problems of the province. He became the resident playwright and director of the company for five years, and the group succeeded in restoring public interest in drama.

Compania Ocampo remained active in the mid 1950s, mounting regular shows often in the town plaza with komedyas and contemporary zarzuelas. Members then included Pons Amurao, Esting Tungol, Curing Mallari, Andres Balagtas, Flor Garcia, and the Manapuls. Providing healthy competition was Compania Paz, a zarzuela company founded by Judge Florentino Torres in the early 1920s.

In 1961, the eminent writer Jose Gallardo of barrio Gulap, Candaba with Andres Balagtas revived the Compania Ocampo. After the demise of Reyes in 1967, Gallardo reorganized the theatrical group again under his own name. The Martial Law curfew imposed in 1972 made it difficult to stage evening performances, so the group was disbanded.

In the mid 1950s, the artists of barrio Lanang, led by the noted Candaba poet Jose Pelayo, orangized themselves into a dramatic troupe known as Compania Crispelita. It soon became a village institution, with its travelling shows all around the province.

In December 1957, the company gave a command performance of their play entitled “Calbario ning Ulila” (Calvary of an orphan).

The story touched the heart strings of Lanang’s drama fans, as the story was something they have seen in the group’s rehearsals, and, in many ways, actually lived—the tyranny of rich landlords, the oppression of peasants , and the final triumph of good versus evil.

The show, directed by Agripino Suba and assisted by apuntador (prompter) Jose Pelayo, and Hugo Ocampo, drew crowds from neighboring barrios. Before an enthusiastic audience, the thespians could not, but give an inspired performance. Providing the musical background was a live band of musicians who also got their share of audience appreciation.

“Our severest critics”, Director Suba said, “are in our own village and if we got their nod, that means we will be welcomed anywhere.

The era of traveling theater companies is long gone, but the people of Candaba can take pride in the fact that, for a few decades,

Candaba’s peripatetic theater groups broke barriers of distance and access to bring their art to their fellow Kapampangans. The era of companias may be long gone, but the legacy of performances of these Candaba artists, playwrights, poets, directors, musicians and stage hands, will always be remembered.

Sources:

Drama in Candaba, The Sunday Times Magazine, 29 Dec. 1957,pp. 15-19.

Cabusao, Romeo C. Candaba, Balayan ning Leguan. pp. 344-345.

Zapanta-Manlapaz, Edna. Kapampangan Literarture: A Historical Survey and Anthology. Ateneo de Manila University Press, Quezon City, Manila. 1981.pp. 25-26

Lacson, Evangelina. Kapampangan Writing: A Select Compendium and Critique. 1984

Showing posts with label Candaba. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Candaba. Show all posts

Monday, November 21, 2016

Monday, October 3, 2016

*409. A BIRD IN THE HAND

BIRDS OF THE SAME FEATHER. A Kapampangan girl holds a fake dove ("pati pati"), a painted flock of which are shown flying or resting on the steps as part of the studio scenography. Our feathered friends have always been an important part of our culture, traditional beliefs, everyday livelihood and folklore. ca. 1917.

They have always been a source of jokes for my Tagalog-speaking friends—these soundalike words “ayup-hayop” and “ibon-ebon” that hold different, but related meanings. “Ibon” is the Tagalog term for “bird”, but its near-homophone –“ebun”—is but an egg in Kapampangan. Similarly, that which Tagalogs call “hayop” (animal), is a mere ‘bird’ (ayup) in Kapampangan.

In the days of yore, however, the secondary definition of “ayop”, as noted in Bergaño’s compilation of Kapampangan words, included brute animals such as cows and carabaos, amphibians, reptiles and insects. Today, “ayup” is a word solely used for our fine-feathered friends.

The wetlands of Candaba are famed for being bird sanctuaries, where migratory birds from other lands leave their original habitat temporarily to escape harsh weather conditions and seek food in the environs of our marshlands.

Birdwatchers from all over the Philippines and around the world have started to discover Candaba’s bird sanctuary, which is being developed as a tourist destination. A collateral event—the Ibon-Ebun (Bird-Egg) Festival is celebrated annually, from Feb. 1-2, to honor not only the town patron, the pugo (quail)-carrying San Nicolas, but also to promote eco-tourism using its varied species of birds as attraction.

Aside from Candaba, there was a time in the 1950s when the sleepy town of San Luis came alive with birdhunters coming in droves to hunt for jack snipes, locally known as “pasdan”. The season for snipes begin in September, when the chill of the northern countries send these birds southbound, with millions finding refuge in Pampanga and Tarlac.

“Pasdans” are prized for their tasty meat, so they are avidly hunted by locals as well as hobbysts from nearby Clark Air Base. The birds often perched on trees that fringed the vast rice paddies and marshes of Pampanga; in fact, they could be found all the way to Concepcion, Tarlac. The small birds are easy to spot by their sheer number. A bigger and more colorful variety—the “pakubo”—is rarer and more elusive. In 1955, the gaming limit for “pasdan” was limited to 50 birds per person.

“Pasdans” are either grilled or cooked adobo-style, a delicacy seldom seen on Pampanga tables today. Our province was once blessed with an abundance of birds of the most bewildering assortment—we even had local names for them.

We had eagles, falcons, hawks (agila, alibasbas, balawe), parrot varieties (katala loru, abukai or Philippine cockatoo, kilakil or white parrot, kulasisi), doves and pigeons ( pati-pati, batubato, the white-eared alimukun ), sparrows (denas paking, denas costa, denas bale, maya) and swallows (layang-layang, sibad, timpapalis). There were marsh birds ( patirik-tirik, uis, dumara), pelicans (kasili, pagala), long-legged herons and egrets (tagak, tikling, kandungangu, bako).

Then, there were birds noted for their colorful and unusual plumage (kuliawan or oriole, luklak or yellow vented bulbul, kansusuit or lyre bird, pabo real or peacock, silingsilingan or pied fantail) and for the cacophony of sounds they create (pipit, siabukut or Philippine coucal, tarat, martinis).

Much of our natural environment have changed irrevocably—caused by years of thoughtless land developments and conversions, illegal logging and deforestation, and of course, global warming. The devastating effects of the Pinatubo eruption also had far-reaching effects on our bird habitats, such that these creatures are no longer familiar to today’s generations, for they are rarely heard or sighted.

Their important roles in our culture and folklore are remembered in myths of old, as in the case of that sacred blue kingfisher from the marshlands of Pampanga, whose appearance foreshadowed events of profound significance--either gainful or grim—to humankind. This revered bird was called “batala”, who gave his name to the mightiest of ancient gods—Bathala.

They have always been a source of jokes for my Tagalog-speaking friends—these soundalike words “ayup-hayop” and “ibon-ebon” that hold different, but related meanings. “Ibon” is the Tagalog term for “bird”, but its near-homophone –“ebun”—is but an egg in Kapampangan. Similarly, that which Tagalogs call “hayop” (animal), is a mere ‘bird’ (ayup) in Kapampangan.

In the days of yore, however, the secondary definition of “ayop”, as noted in Bergaño’s compilation of Kapampangan words, included brute animals such as cows and carabaos, amphibians, reptiles and insects. Today, “ayup” is a word solely used for our fine-feathered friends.

The wetlands of Candaba are famed for being bird sanctuaries, where migratory birds from other lands leave their original habitat temporarily to escape harsh weather conditions and seek food in the environs of our marshlands.

Birdwatchers from all over the Philippines and around the world have started to discover Candaba’s bird sanctuary, which is being developed as a tourist destination. A collateral event—the Ibon-Ebun (Bird-Egg) Festival is celebrated annually, from Feb. 1-2, to honor not only the town patron, the pugo (quail)-carrying San Nicolas, but also to promote eco-tourism using its varied species of birds as attraction.

Aside from Candaba, there was a time in the 1950s when the sleepy town of San Luis came alive with birdhunters coming in droves to hunt for jack snipes, locally known as “pasdan”. The season for snipes begin in September, when the chill of the northern countries send these birds southbound, with millions finding refuge in Pampanga and Tarlac.

“Pasdans” are prized for their tasty meat, so they are avidly hunted by locals as well as hobbysts from nearby Clark Air Base. The birds often perched on trees that fringed the vast rice paddies and marshes of Pampanga; in fact, they could be found all the way to Concepcion, Tarlac. The small birds are easy to spot by their sheer number. A bigger and more colorful variety—the “pakubo”—is rarer and more elusive. In 1955, the gaming limit for “pasdan” was limited to 50 birds per person.

“Pasdans” are either grilled or cooked adobo-style, a delicacy seldom seen on Pampanga tables today. Our province was once blessed with an abundance of birds of the most bewildering assortment—we even had local names for them.

We had eagles, falcons, hawks (agila, alibasbas, balawe), parrot varieties (katala loru, abukai or Philippine cockatoo, kilakil or white parrot, kulasisi), doves and pigeons ( pati-pati, batubato, the white-eared alimukun ), sparrows (denas paking, denas costa, denas bale, maya) and swallows (layang-layang, sibad, timpapalis). There were marsh birds ( patirik-tirik, uis, dumara), pelicans (kasili, pagala), long-legged herons and egrets (tagak, tikling, kandungangu, bako).

Then, there were birds noted for their colorful and unusual plumage (kuliawan or oriole, luklak or yellow vented bulbul, kansusuit or lyre bird, pabo real or peacock, silingsilingan or pied fantail) and for the cacophony of sounds they create (pipit, siabukut or Philippine coucal, tarat, martinis).

Much of our natural environment have changed irrevocably—caused by years of thoughtless land developments and conversions, illegal logging and deforestation, and of course, global warming. The devastating effects of the Pinatubo eruption also had far-reaching effects on our bird habitats, such that these creatures are no longer familiar to today’s generations, for they are rarely heard or sighted.

Their important roles in our culture and folklore are remembered in myths of old, as in the case of that sacred blue kingfisher from the marshlands of Pampanga, whose appearance foreshadowed events of profound significance--either gainful or grim—to humankind. This revered bird was called “batala”, who gave his name to the mightiest of ancient gods—Bathala.

Friday, September 16, 2016

*407. FISHING FOR COMPLIMENTS

Being in the central plains of Luzon, people are sometimes surprised to know that Pampanga, too, has a fishing trade, an industry associated with coastal places like Navotas, Malabon, and the Visayan islands.

Actually, Pampanga has an area that is heavily watered by the great Pampanga River and its tributaries. In the delta towns of Guagua, Lubao and Sasmuan, as well as in the low-lying towns of Masantol, Macabebe, San Luis and Candaba, fisheries is a source of livelihood.

Fisherfolks catch fish either by the traditional method of setting traps in the water or by building fish ponds, which are a common sight in Macabebe and Masantol, where they are diked and seeded with fingerlings.

Upon maturity, the fish are harvested by letting the waters spill out. Large fishponds also served as swimming holes and picnic sites in the 20s-30s, as they not only had picturesque locations but they also provided an unlimited number of fish for food. Unfortunately, ponds have also become contributors to the worsening of the flood situations in these areas after the silting of major estuaries caused by the Pinatubo eruption. Fishponds have also been blamed for the disappearance of mangroves since their proliferation beginning in the 1970s.

In Candaba, depending on the season, the swamp serves a dual function. During summer, it is used as an agricultural field to plant rice, vegetables and grow watermelons. But when the wet season arrives and rainwater fill the swamp, it turns into a lake teeming with bangus (milkfish), tilapia, paro (shrimp), ema (crab) and bulig (mudfish). (Tip: the Friday Candaba Market in Clark is the go-to place for the freshest catch of fish, shrimps, crabs, eels and other crustaceans).

“Asan” is the Kapampangan term for “fish”, but today, when people ask “Nanung asan yu?”, they also mean “What’s your food?”—whether your “ulam” (viand) be made of meat or vegetable. “Masan” is a verb meaning “to eat”, it is specific to eating cooked fish or meat, thus, “masan asan” is “eat cooked fish”. There is hardly a difference between “asan” and “ulam”, as used today, which underlines the importance of fish in the life of the Kapampangan.

While today’s Kapampangan is familiar with fish like itu (catfish), kanduli (salmon catfish) , sapsap (ponyfish) and talangka (small crabs), our old folks knew other kinds of fish with fascinating names that may sound alien to our ears today. A goldfish was called “talangtalang”, while a “pacut” is a small crab. Another name for kanduli is “tabangongo”, a “talunasan”, an edible eel. A “palimanoc” is a ray fish, a “tag-agan”—a swordfish, and its small look-alike is called “balulungi”,

Our contribution to the culinary world include fish-based treats that include “burung asan” (using bulig),”balo-balo” (using tilapia, gurami and shrimp), and “taba ning talangka”. We also have our delectable versions of sisig bangus, pesang bulig and rellenong bangus. During Lent, we prepare sarsiado, escabeche, suam a tulya, and seafood bringhi. In our fiestas and holidays, we serve fancy fish dishes like Pescado el Gratin, Chuletas (fish fillet), and Pescado con Mayonesa. For many Kapampangans, there’s never a day without fish on the table.

“Nanung asan yu?”

Labels:

Candaba,

fishing,

Guagua,

Lubao,

Macabebe,

Masantol,

Pampanga commerce,

Pampanga industry,

San Luis,

Sasmuan

Thursday, October 8, 2015

*389. Training To Be Red: STALIN UNIVERSITY

RED ALERT. Barrio Sinipit in Cabiao, Nueva Ecija, lies under the shadow of Mount Arayat. The strategically-located barrio was the site of an informal training school for Red cadres known as Stalin University. ca. 1959.

Communism was a new ideology that was embraced early by the peasantry in their fight against tenant oppression. But one did not just turn red in an instant, he had to be indoctrinated in the ways of the new movement—from its fundamental beliefs and principles to its concept of resistance and armed uprising. The training school for such purpose was set up in a place aptly named Barrio Sinipit, in Cabiao Nueva Ecjia—which, in Kapampangan means “ hemmed-in, suppressed, repressed”. The school was called Stalin University—named after the Moscow-based institution founded by Communist International on 21 April 1921.

This Kapampangan-speaking barrio, portions of which lie in the Candaba Swamp, was the perfect place for such a training school—Barrio Sinipit had always been hard-pressed from all directions, regularly raided by marauders, it houses burned and women raped. The barrio’s position and background made Sinipit the choice site for secret meetings by members and leaders of the so-called “Pambansang Kaisahang Magbubukid sa Pilipinas” (National Organization of Peasants in the Philippines).

It was in 1936 that the PKMP established a training school for future leaders of this movement that was founded for the cause of oppressed peasants. In later years, these products of Stalin University would identify themselves as Huk guerrillas who shifted their fight from enemy invaders during the War, to abusive landlords and hacenderos. Many would also take on leading roles in the Communist Party of the Philippines and identify themselves as guerrillas of the Huk movement.

Stalin University was not a permanent building; its site was moveable and changeable—it could be under the canopy of a huge tree one day, and a ramshackle hut the next. This was so, because the instructors were the subject of manhunt by government intelligent officers. They were culled from the outside, who had knowledge of the conditions and feelings of Sinipit peasants.

One tenant-farmer recall that “they were glib-tongue, very convincing, and they spoke of brighter things for us”. They would come with mimeographed notes and pamphlets in different languages. And they would talk of holding reprisals against abusive landlords. The Philippine Government knew of this Stalin University and it would send soldiers to swoop down on the clandestine school. But the class would always be a step ahead, moving to secret refuges in Bulacan or towards hideaways in Arayat or the swamps of Candaba.

The Magsaysay Era ushered in a new purposeful period—to restore common people’s confidence in the government. Magsaysay sparked the revival of nationalism, and promised rural reforms. He addressed not only the issue of dissidence in the back country but also the disaffection of peasants because of grievances that remained unredressed. He established the President’s Complaint and Action Committee to look into such matters, such as the festering problem of share-cropping. Huk Chief Luis Taruc even sent a feeler to Commissioner Manahan when he heard Magsaysay’s speech about rural reforms and was curious to learn more. In time, Taruc admitted that Magsaysay’s barrio program had made the Huk struggle aimless.

Thus, Stalin University was abandoned as the Huks took their movement to the hills, leaving Barrio Sinipit in peace once more. By 1959, the barrio was back on its feet, a thriving community blessed with rich soil and hardworking people. No many remember that not so long ago, beneath the shadow of Mount Arayat, there was a Nueva Ecija barrio where once Red cadres trained, in a school without a campus, known by the name Stalin University.

Communism was a new ideology that was embraced early by the peasantry in their fight against tenant oppression. But one did not just turn red in an instant, he had to be indoctrinated in the ways of the new movement—from its fundamental beliefs and principles to its concept of resistance and armed uprising. The training school for such purpose was set up in a place aptly named Barrio Sinipit, in Cabiao Nueva Ecjia—which, in Kapampangan means “ hemmed-in, suppressed, repressed”. The school was called Stalin University—named after the Moscow-based institution founded by Communist International on 21 April 1921.

This Kapampangan-speaking barrio, portions of which lie in the Candaba Swamp, was the perfect place for such a training school—Barrio Sinipit had always been hard-pressed from all directions, regularly raided by marauders, it houses burned and women raped. The barrio’s position and background made Sinipit the choice site for secret meetings by members and leaders of the so-called “Pambansang Kaisahang Magbubukid sa Pilipinas” (National Organization of Peasants in the Philippines).

It was in 1936 that the PKMP established a training school for future leaders of this movement that was founded for the cause of oppressed peasants. In later years, these products of Stalin University would identify themselves as Huk guerrillas who shifted their fight from enemy invaders during the War, to abusive landlords and hacenderos. Many would also take on leading roles in the Communist Party of the Philippines and identify themselves as guerrillas of the Huk movement.

Stalin University was not a permanent building; its site was moveable and changeable—it could be under the canopy of a huge tree one day, and a ramshackle hut the next. This was so, because the instructors were the subject of manhunt by government intelligent officers. They were culled from the outside, who had knowledge of the conditions and feelings of Sinipit peasants.

One tenant-farmer recall that “they were glib-tongue, very convincing, and they spoke of brighter things for us”. They would come with mimeographed notes and pamphlets in different languages. And they would talk of holding reprisals against abusive landlords. The Philippine Government knew of this Stalin University and it would send soldiers to swoop down on the clandestine school. But the class would always be a step ahead, moving to secret refuges in Bulacan or towards hideaways in Arayat or the swamps of Candaba.

The Magsaysay Era ushered in a new purposeful period—to restore common people’s confidence in the government. Magsaysay sparked the revival of nationalism, and promised rural reforms. He addressed not only the issue of dissidence in the back country but also the disaffection of peasants because of grievances that remained unredressed. He established the President’s Complaint and Action Committee to look into such matters, such as the festering problem of share-cropping. Huk Chief Luis Taruc even sent a feeler to Commissioner Manahan when he heard Magsaysay’s speech about rural reforms and was curious to learn more. In time, Taruc admitted that Magsaysay’s barrio program had made the Huk struggle aimless.

Labels:

Cabiao,

Candaba,

Communism,

Huks,

NPA,

Nueva Ecija,

Pampanga,

social history

Saturday, June 21, 2014

*369. KAPAMPANGANS AT THE 1904 ST. LOUIS’ WORLD’S FAIR

FILIPINAS AT THE FAIR! The Philippine Exhibit was assigned the largest space in the fairgrounds of the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair, and a multitude of structures were built to serve as exhibit halls and residences of some 1,100 Filipinos (mostly tribal groups) flown in to animate the event. No wonder, the Philippine Exhibit caused a major sensation

“Meet me at St. Louis…meet me at the Fair!”

So goes the lyrics of the period song that served as the unofficial theme of a magnificent American fair that was dubbed as “the greatest of expositions”, surpassing everything the world has seen before, in terms of cost, size and splendor, variety of views, attendance and duration.

The 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, popularly known as the St. Louis World’s Fair, opened officially on 30 April 1904, to mark the 100th anniversary of the purchase of Louisiana from France by the U.S.- a vast area that comprised almost 1/3 of continental America. From this land were carved the states of Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Oklahoma and sections of Colorado, Minnesota and Wyoming.

Save for Delaware and Florida, all the states and territories of America participated in all the activities at the sprawling 1,275 acre fairgrounds that took all of 6 years to build. As a U.S. territory, the Philippines joined 45 nations in organizing a delegation as well as the construction of its own exhibit grounds—the largest in the fair-- to house pavilions, recreated villages, presentations and native Filipino groups.

Much have been said about the Philippine representation that included “living museums” with ethnic tribes (Samal, Negrito, Igorottes, Bagobos), and regional groups (Visayans, Tagalogs) showing their traditional way of living in replicated villages.

Before large audiences, Igorots demonstrated their culinary practices by eating dogs, while Negritos shot arrows and climbed trees. A pair of Filipino midgets were also featured stars, together with English-speaking, harp-playing Tagalas who represented the more “civilized’ side of the Philippines.

On a more positive note, the Philippine Constabulary Band dazzled and thrilled crowds with their impressive and stirring performance of march music while the Philippine Scouts, composed mostly of smartly-dressed Macabebe soldiers ("Little Macs", as they were called by their American fans) , performed military drills with precision and aplomb.

Then there were the superlative government exhibits that showcased the richness of Philippine talents and resources. There were exhibits in various categories: Forestry, Arts, Crafts, Cuisine, Education, Agriculture and Horticulture, Fish, Game and Water Transport and other industries. Tasked with the purchase of collecting and installing these distinctively Filipino exhibits for the St. Louis World’s Fair was the Philippine Exposition Board, specially created by the Philippine Commission.

The Board was allotted an initial budget of $125,000, with a further appropriation of up to $250,000 to mount a world-class exhibit that would show the commercial, industrial, agricultural, cultural, educational and economic gains made by our islands under Mother America.

Recognitions were given by the organizers of the World’s Fair for country participants where their entries were judged by an international jury. Over 6,000 of various colors were won by the Philippines. Among those granted the honors were many outstanding Kapampangans who were represented by their inventive and creative works that wowed both the crowds of St. Louis and also the esteemed jury.

In the category of Ethnography, the Silver Prize went to the Negrito Tribe (tied with the Bagobos) that counted Aetas from Pampanga as among the tribe members. They wre represented by Capt. Medio of Sinababawan and Capt. Batu Tallos, of Litang Pampanga.

The Products of Fisheries yielded the following Kapampangan winners who produced innovative fishing equipment. Bronze Medals: Ambrosio Evangelista, Diego Reyes (Candaba); Fulgencio Matias (Sta. Ana); Macario Tañedo (Tarlac). Honorable Mentions: Alfredo Arnold, Epifanio Arceo, Pedro Lugue, Jacinto De Leon, Pascual Lugue, Mario Torres (Apalit); Eugenio Canlas, Teodoro de los Santos (Sto. Tomas); Andres Lagman (Minalin); Rita Pangan (Porac); Thos. J. Mair, Medeo Captacio (identified only as coming from Pampanga).

Pampanga schools also performed commendably, with various winners in the Public School Exhibits, Elementary Division. Bronze medal winners include the town schools of Apalit, Arayat, Bacolor, Candaba and San Fernando, while Honorable Mentions were merited by Betis, Guagua and Mabalacat.

In the Secondary School division, Pampanga High School of San Fernando too home the Bronze. From among entries in the General Collective Exhibit category, Mexico was chosen to receive a Silver Medal. The Bronze went to Macabebe and San Fernando, while Honorable Mentions list included Bacolor, Candaba, Floridablanca, Magalang and Sta. Rita.

The Fine Arts competition produced two Pampanga residents: Rafael Gil who won Silver for his mother-of-pearl art creation. Gil, and the highly regarded Bacolor artist, Simeon Flores (posthumous), also won Honorable Mentions for their paintings.

The culinary traditions of Pampanga were made known to the world at the St. Louis World’s Fair through the sweet kitchen concoctions of several ‘kabalens’. Angeles was ably represented by Trifana Angeles Angeles (preserved orange peel) ; Irene Canlas (preserved melon); Carlota C. Henson (preserves and jellies); Januario Lacson (santol preserves); Isabel Mercado (preserved limoncito); Atanacio Rivera de Morales (santol preserves, buri palm preserves); Zoilo and Marcelino Nepomuceno (mango jelly); Aurelia Torres (santol preserves) andYap Siong (anisada corriente, anis espaseosa) Mabalaqueñas also tickled taste buds with their homemade desserts: Rafaela Ramos Angeles (preserved fruit, santol preserves); Maria Guadalupe Castro (santol jelly) and Justa de Castro (kamias fruit preserve).

The World’s Fair at St. Louis closed at midnight on 1 December 1904, and was declared a huge success—thanks in part to the blockbuster Philippine exhibits enriched by the modest contributions of Kapampangans who proved equal to the challenge, to emerge as world-class citizens.

Tuesday, February 18, 2014

*363. PAMPANGUEÑAS AT LA CONCORDIA

CAPAMPANGAN CONCORDIANS. Kapampangan internas of La Concordia College, most from well-known families of the province, are shown in this 1928 photo at the school grounds.

In the 20s and 30s, class pictures were taken and classified not just by grade levels or sections, but also by the provinces from where the students came from. This custom of regional classification arose at the same time as school clubs were being formed based on one’s provenance. In the early days of the U.P. , there were officially-recognized clubs such as the Pampanga High School Club, which counted as its exclusive members, only PHS alumni.

I have seen many group pictures bearing captions as “Seminaristas de la Pampanga”, “Pampango-Speaking Students at Philippine Normal School”, and most recently, this snapshot of a bevy of young Kapampangan ladies, identified as “Pampangueñas at Concordia”. This picture, which dates from 1928, not only identified the La Concordia students by number, but also the towns from which they originated.

Colegio de la Inmaculada Concepcion de la Concordia was a school founded by Dña. Margarita Roxas de Ayala in 1868, built on her estate located on Pedro Gil in Paco. She donated this land for the erection of a girl’s school which was run by the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. The school, with its initial staff of “imported”teachers, attracted students like Rizal’s sisters—Olimpia, Saturnina and Soledad, and other children of prominent families, from nearby provinces, Pampanga included.

This photo shows young Kapampangan “internas” (student boarders) whose surnames reveal their privileged background. Detached from the comforts of their homes and familiarity of families, these girls were sent to Manila, with their board and lodging paid for monthly by their parents, with the goal of giving them proper education, befitting young women of their generation.

So, whatever happened to these La Concordia Girls of 1928. I tried my best to find out what happened after their school years in one of Manila’s elite girls’ schools, guided by the names written on the back of the photo.

Fil-Am Barbara Setzer (1) and her younger sister Estela (15) were both from Angeles. Their parents were George Seltzer, and American, and Maria Dolores Lumanlan, who were married sometime in 1912. All 6 children (including Mercedes, Frank, John and Clara) were born in Angeles. Barbara was their second eldest, born on 4 December 1912. She died in San Francisco, California. Benita Estela Seltzer or Estela (born 21 March 1918) was just 10 years old when this picture was taken; she too, moved to the U.S. when she came of age.

Catalina Madrid (2) is listed as having Macabebe as her hometown while Girl #3 is unidentified. Another Macabebe lass is Gregoria Alfonso (10); Alfonso descendants continue to reside in the town to this day.

Araceli Berenguer (4) comes from the prominent Berenguer family of Arayat; she has three other kabalens in this photo, Maria Tinio (16), Flora Kabigting (6) with a familiar surname now associated with the halo-halo that made the town famous, and Rosario Dizon (13), who grew up to be a national Philippine Free Press Beauty of 1929.

Little is known of Salud Canivel (5) who is from Candaba as well as Girl No. 14, identified only as Natividad R. Margarita Coronel (7) comes from the well-known Coronel family of Betis, Guagua. After La Concordia, she went to the University of Santo Tomas, where she excelled in Botany. A rare angiosperm she collected in Betis in 1934 is included today at the UST Herbarium.

Loreto Feliciano (8) and her younger sister, Luz (17) are natives of Bamban, Tarlac. Loreto is better known as the wife of the late Robert ”Uncle Bob” Stewart, the pioneer TV broadcaster who founded DZBB Channel 7, and host of the long-running TV show, “Uncle Bob Lucky 7 Club ”.

The Nepomucenos of Angeles are represented by cousins Pilar (9) and Imelda (12). Feliza Adoracion Imelda Nepomuceno (b. 29 Nov. 1912) was the daughter of Jose Fermin Nepomuceno with Paula Villanueva. She married Dr. Jose Guzman Galura later in life.

Her first cousin Pilar, (Maria Agustina Pilar Nepomuceno, b. 13 October 1911) was the daughter of Geronimo Mariano (Jose Fermin’s older brother) and Gertrudes Ayson. As Miss Angeles 1933, Pilar represented the town in the search for Miss Pampanga at the 1933 Pampanga Carnival and Exposition. She later married Dr. Conrado T. Manankil and a daughter, Marietta, also became Miss Angeles 1955.

What we know of their later lives as adult women suggests that they did fairly well, making good accounts of themselves as mostly successful mothers and homemakers. But in 1928, they were just a bunch of young Kapampangan La Concordia interns, bound together by a common tongue and culture—sweet and giggly as all other typical girls of their age---with the prospects of the future still far, far away.

In the 20s and 30s, class pictures were taken and classified not just by grade levels or sections, but also by the provinces from where the students came from. This custom of regional classification arose at the same time as school clubs were being formed based on one’s provenance. In the early days of the U.P. , there were officially-recognized clubs such as the Pampanga High School Club, which counted as its exclusive members, only PHS alumni.

I have seen many group pictures bearing captions as “Seminaristas de la Pampanga”, “Pampango-Speaking Students at Philippine Normal School”, and most recently, this snapshot of a bevy of young Kapampangan ladies, identified as “Pampangueñas at Concordia”. This picture, which dates from 1928, not only identified the La Concordia students by number, but also the towns from which they originated.

Colegio de la Inmaculada Concepcion de la Concordia was a school founded by Dña. Margarita Roxas de Ayala in 1868, built on her estate located on Pedro Gil in Paco. She donated this land for the erection of a girl’s school which was run by the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. The school, with its initial staff of “imported”teachers, attracted students like Rizal’s sisters—Olimpia, Saturnina and Soledad, and other children of prominent families, from nearby provinces, Pampanga included.

This photo shows young Kapampangan “internas” (student boarders) whose surnames reveal their privileged background. Detached from the comforts of their homes and familiarity of families, these girls were sent to Manila, with their board and lodging paid for monthly by their parents, with the goal of giving them proper education, befitting young women of their generation.

So, whatever happened to these La Concordia Girls of 1928. I tried my best to find out what happened after their school years in one of Manila’s elite girls’ schools, guided by the names written on the back of the photo.

Fil-Am Barbara Setzer (1) and her younger sister Estela (15) were both from Angeles. Their parents were George Seltzer, and American, and Maria Dolores Lumanlan, who were married sometime in 1912. All 6 children (including Mercedes, Frank, John and Clara) were born in Angeles. Barbara was their second eldest, born on 4 December 1912. She died in San Francisco, California. Benita Estela Seltzer or Estela (born 21 March 1918) was just 10 years old when this picture was taken; she too, moved to the U.S. when she came of age.

Catalina Madrid (2) is listed as having Macabebe as her hometown while Girl #3 is unidentified. Another Macabebe lass is Gregoria Alfonso (10); Alfonso descendants continue to reside in the town to this day.

Araceli Berenguer (4) comes from the prominent Berenguer family of Arayat; she has three other kabalens in this photo, Maria Tinio (16), Flora Kabigting (6) with a familiar surname now associated with the halo-halo that made the town famous, and Rosario Dizon (13), who grew up to be a national Philippine Free Press Beauty of 1929.

Little is known of Salud Canivel (5) who is from Candaba as well as Girl No. 14, identified only as Natividad R. Margarita Coronel (7) comes from the well-known Coronel family of Betis, Guagua. After La Concordia, she went to the University of Santo Tomas, where she excelled in Botany. A rare angiosperm she collected in Betis in 1934 is included today at the UST Herbarium.

Loreto Feliciano (8) and her younger sister, Luz (17) are natives of Bamban, Tarlac. Loreto is better known as the wife of the late Robert ”Uncle Bob” Stewart, the pioneer TV broadcaster who founded DZBB Channel 7, and host of the long-running TV show, “Uncle Bob Lucky 7 Club ”.

The Nepomucenos of Angeles are represented by cousins Pilar (9) and Imelda (12). Feliza Adoracion Imelda Nepomuceno (b. 29 Nov. 1912) was the daughter of Jose Fermin Nepomuceno with Paula Villanueva. She married Dr. Jose Guzman Galura later in life.

Her first cousin Pilar, (Maria Agustina Pilar Nepomuceno, b. 13 October 1911) was the daughter of Geronimo Mariano (Jose Fermin’s older brother) and Gertrudes Ayson. As Miss Angeles 1933, Pilar represented the town in the search for Miss Pampanga at the 1933 Pampanga Carnival and Exposition. She later married Dr. Conrado T. Manankil and a daughter, Marietta, also became Miss Angeles 1955.

What we know of their later lives as adult women suggests that they did fairly well, making good accounts of themselves as mostly successful mothers and homemakers. But in 1928, they were just a bunch of young Kapampangan La Concordia interns, bound together by a common tongue and culture—sweet and giggly as all other typical girls of their age---with the prospects of the future still far, far away.

Labels:

Angeles,

Arayat,

Bamban,

Candaba,

Kapampangan personalities,

Macabebe,

Pampanga,

Pampanga schools

Saturday, December 21, 2013

*356. Pampanga's Churches: SAN ANDRES APOSTOL CHURCH, Candaba

SAN ANDRES APOSTOL CHURCH. Candaba's center of worship, as it appeared around 1911-1912, from the Luther Parker Collection.

Watermelons, swampy lands, migratory birds—all these conjure images of one of Pampanga’s oldest towns during the wet season—Candaba, which is located on the plains near the Pampanga River, characterized by a large swamp in its midst. The “pinac”, formed by estuaries and rivers from Nueva Ecija, is a rich source of income for most of the people of Candaba, yielding fish, farm produce and the sweetest “pakwan” around.

Centuries before, Candaba had also impressed the Spaniards for its flourishing economy, not to mention its antiquity, calling it “Little Castilla”. Augustinians quickly descended upon the wetlands to claim Candaba as house of their order in 1575, appending it to the Calumpit convent with Fray Francisco de Ortega as prior. Its first recognized cura, however, is Fray Francisco Manrique, who came all the way from the Visayas.

The Bishop of Manila, Fray Domingo de Salazar, cause Candaba to become an important mission center for the evangelization of other towns like Arayat and Pinpin (Sta. Ana). A church of light materials, dedicated to the apostle San Andres, was erected and by 1591, a convent had also been built.

As the town progressed, a stone edifice replaced the primitive church, built from 1665-69, under the helm of the dynamic church builder, Fray Jose dela Cruz. There is an account of a certain Fray Felipe Guevara building a grimpola and a campanario as early as 1875.

A later successor, Fray Esteban Ibeas, added the dome in 1878. He added bells from 1879-81, dedicated to San Agustin, San Jose, San Andres, Sagrado Corazon de Jesus and Virgen dela Consolacion. In 1881, Fray Antonio Bravo constructed the bell tower and added one more bell, dedicated to the Holy Trinity. All bells were cast by Hilarion Sunico of Binondo.

By the time the “pisamban batu” was done, it measured 60 meters long, 13 meters wide and 13 meters high. The campanario was repaired in 1890. In 1897, parish duties were transferred to the Filipino secular clergy. The first Filipino priest to serve was Padre Eulogio Ocampo.

In modern times, the church interior was damaged by a typhoon in the 60s, and was restored that same year. Previous to this, there are no records of damages caused by the acts of nature.

Today, the church has a very simple architecture, with not much ornamental details. A series of columns and depressed arches define its façade, while its protruding triangular pediment echoes that pleasing plainness. The arcaded convent front features semi-circular arches. The Church of San Andres Apostol of Candaba observes the fiesta of its patron every year, on the 30th of November.

Watermelons, swampy lands, migratory birds—all these conjure images of one of Pampanga’s oldest towns during the wet season—Candaba, which is located on the plains near the Pampanga River, characterized by a large swamp in its midst. The “pinac”, formed by estuaries and rivers from Nueva Ecija, is a rich source of income for most of the people of Candaba, yielding fish, farm produce and the sweetest “pakwan” around.

Centuries before, Candaba had also impressed the Spaniards for its flourishing economy, not to mention its antiquity, calling it “Little Castilla”. Augustinians quickly descended upon the wetlands to claim Candaba as house of their order in 1575, appending it to the Calumpit convent with Fray Francisco de Ortega as prior. Its first recognized cura, however, is Fray Francisco Manrique, who came all the way from the Visayas.

The Bishop of Manila, Fray Domingo de Salazar, cause Candaba to become an important mission center for the evangelization of other towns like Arayat and Pinpin (Sta. Ana). A church of light materials, dedicated to the apostle San Andres, was erected and by 1591, a convent had also been built.

As the town progressed, a stone edifice replaced the primitive church, built from 1665-69, under the helm of the dynamic church builder, Fray Jose dela Cruz. There is an account of a certain Fray Felipe Guevara building a grimpola and a campanario as early as 1875.

A later successor, Fray Esteban Ibeas, added the dome in 1878. He added bells from 1879-81, dedicated to San Agustin, San Jose, San Andres, Sagrado Corazon de Jesus and Virgen dela Consolacion. In 1881, Fray Antonio Bravo constructed the bell tower and added one more bell, dedicated to the Holy Trinity. All bells were cast by Hilarion Sunico of Binondo.

By the time the “pisamban batu” was done, it measured 60 meters long, 13 meters wide and 13 meters high. The campanario was repaired in 1890. In 1897, parish duties were transferred to the Filipino secular clergy. The first Filipino priest to serve was Padre Eulogio Ocampo.

In modern times, the church interior was damaged by a typhoon in the 60s, and was restored that same year. Previous to this, there are no records of damages caused by the acts of nature.

Today, the church has a very simple architecture, with not much ornamental details. A series of columns and depressed arches define its façade, while its protruding triangular pediment echoes that pleasing plainness. The arcaded convent front features semi-circular arches. The Church of San Andres Apostol of Candaba observes the fiesta of its patron every year, on the 30th of November.

Monday, April 2, 2012

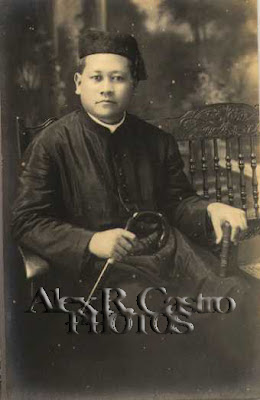

*288. The Seminary Years of REV. FR. TEODORO S. TANTENGCO

THE CHOSEN. Teodoro Tantengco of Angeles was one of 12 seminarians who started their priestly studies at the San Carlos Seminary beginning in 1908. Eight years later, he was ordained as a priest. He was the long-time cura parocco of San Simon.

THE CHOSEN. Teodoro Tantengco of Angeles was one of 12 seminarians who started their priestly studies at the San Carlos Seminary beginning in 1908. Eight years later, he was ordained as a priest. He was the long-time cura parocco of San Simon. In 1908, twelve new seminarians entered the august halls of the Conciliar San Carlos, the first diocesan seminary founded in the Philippines. That time, the seminary was located along Arzobispo Street in Intramuros, beside the new San Ignacio Church. Three years earlier, the American Archbishop Jeremiah Harty had turned over the administration of the premiere seminary in the country to the Jesuits.

Of the 12 seminaristas, two were full-blooded Kapampangans and both from the town of Angeles—Felipe de Guzman and Teodoro Tantengco y Sanchez. Teodoro had entered just two months ahead of Felipe, on 1 July 1908. San Carlos had quite a substantial number of Kapampangan seminaristas enrolled even in those years, coming fromsuch towns as Betis (Victoriano Basco, Mariano Sunglao, Alberto Roque, Mateo Vitug); Sta. Rita (Anacleto David, Pablo Camilo, Eusebio Guanlao, Mariano Trifon Carlos, Prudencio David); Macabebe (Brigido Panlilio, Atanacio Hernandez, Maximo Manuguid, Pedro Jaime); Bacolor (Rodolfo Fajardo, Tomas Dimacali, Vicente Neri); Porac (Mariano Santos); Angeles (Pablo Tablante); Guagua (Laureano de los Reyes) and Candaba (Lucas de Ocampo).

Seminary life was conducted under the watchful eye of the Rector, Fr. Pio Pi and the Minister, Fr. Mariano Juan. Teodoro and his classmates were drilled in Liturgy, Music, English and Ascetics. Moral Theology and Philosophy were taught at santo Tomas while other courses like Math, Greek, French and even Gregorian Chants were also offered. Discipline was exact; some form of corporal punishment were meted out for acts of disobedience—like being put on silence and making public retractions of some kind.

Out of the classrooms, the Carlistas were employed in the Cathedral services and liturgical events, like in the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Pius X as a priest. The seminaristas assisted in the altar services at the mass officiated at the Manila Cathedral. Similarly, the class were mobilized to attend to Archbishop Michael Kelly from Sydney, Australia who had come to Manila for a short visit.

In 1909, Teodoro was present at the consecration of Bishop Dennis Dougherty’s successor, Bishop Carroll, as the Bishop of Vigan. The class also performed preaching duties at the Bilibid Prison and at the San Lazaro Hospital, where the Carlistas ministered to the needs of the patients.

There was no rest during their vacation as Teodoro took classes in Latin, English and Tagalog, even as the superiors organized trips to Sta. Rita, Angeles, Dolores, Porac and Guagua. There were all-day picnics and excursions in Cainta, Cavite, Malabon, San Pedro Makati, Sta. Ana and at the hacienda of a certain Captain Narciso in Orani. Regular “dias de campo” were scheduled in Pasay and Malabon, where the youths swam, played with their bands and refreshed themselves with tuba, melons and ‘agua fresca’.

On 10 April 1910, the Carlistas took part in a historic church event which saw the establishment of four dioceses by Pius X—Calbayog, Lipa, Tuguegarao and Zamboanga. The seminarians were in full attendance to mark this important occasion for the Philippine church. The next year, the seminaristas were allowed to attend the Manila Carnival from Feb. 21-28 at Luneta, where they thrilled to the sight of the aerial acrobatics performed by American pilot Mars.

Teodoro and his classmates were taken by surprise on 17 August 1911, when they received orders from Archbishop Harty to transfer all San Carlos seminarians to the Seminario de San Francisco Javier (the old Colegio de San Jose) located along Padre Faura St. Teodoro was one of 30 seminarians who moved to San Javier, a merger-transfer that would last for 2 years, until the seminary closed in 1913.

With the termination of the Jesuit administration, the seminarians made their final move to a refurbished building in Mandaluyong, which was constructed by Augustinians in 1716 and abandoned in 1900. The Vincentian fathers (Congregation of the Mission) took over the management of the new site of Seminario de San Carlos.

It was here that Teodoro Tantengco, finished his priestly studies which culminated in his ordination in 1916. He was assigned immediately back to his home province in Pampanga, first as assistant priest of Masantol, then as the cura parocco of San Simon which he served for many fruitful years. In 1947, he was in Tayuman, Sta. Cruz.

The accomplished and well-loved priest passed away in San Fernando in 1954. A nephew, Betis-born Teodulfo Tantengco followed in his footsteps, enrolling in his uncle’s alma mater and, after ordination, served various parishes like Arayat and Dau, Mabalacat, Pampanga until his death in 1999.

There was no rest during their vacation as Teodoro took classes in Latin, English and Tagalog, even as the superiors organized trips to Sta. Rita, Angeles, Dolores, Porac and Guagua. There were all-day picnics and excursions in Cainta, Cavite, Malabon, San Pedro Makati, Sta. Ana and at the hacienda of a certain Captain Narciso in Orani. Regular “dias de campo” were scheduled in Pasay and Malabon, where the youths swam, played with their bands and refreshed themselves with tuba, melons and ‘agua fresca’.

On 10 April 1910, the Carlistas took part in a historic church event which saw the establishment of four dioceses by Pius X—Calbayog, Lipa, Tuguegarao and Zamboanga. The seminarians were in full attendance to mark this important occasion for the Philippine church. The next year, the seminaristas were allowed to attend the Manila Carnival from Feb. 21-28 at Luneta, where they thrilled to the sight of the aerial acrobatics performed by American pilot Mars.

Teodoro and his classmates were taken by surprise on 17 August 1911, when they received orders from Archbishop Harty to transfer all San Carlos seminarians to the Seminario de San Francisco Javier (the old Colegio de San Jose) located along Padre Faura St. Teodoro was one of 30 seminarians who moved to San Javier, a merger-transfer that would last for 2 years, until the seminary closed in 1913.

With the termination of the Jesuit administration, the seminarians made their final move to a refurbished building in Mandaluyong, which was constructed by Augustinians in 1716 and abandoned in 1900. The Vincentian fathers (Congregation of the Mission) took over the management of the new site of Seminario de San Carlos.

It was here that Teodoro Tantengco, finished his priestly studies which culminated in his ordination in 1916. He was assigned immediately back to his home province in Pampanga, first as assistant priest of Masantol, then as the cura parocco of San Simon which he served for many fruitful years. In 1947, he was in Tayuman, Sta. Cruz.

The accomplished and well-loved priest passed away in San Fernando in 1954. A nephew, Betis-born Teodulfo Tantengco followed in his footsteps, enrolling in his uncle’s alma mater and, after ordination, served various parishes like Arayat and Dau, Mabalacat, Pampanga until his death in 1999.

Labels:

Angeles,

Bacolor,

Betis,

Candaba,

Guagua,

Pampanga,

Pampanga missionaries,

Philippines,

Sta. Rita

Monday, March 5, 2012

*284. CANDABA CENTRAL SCHOOL

CANDABA CLASS OF '48. Grade Two students of Candaba Central School, post-war batch 1947-1948.

CANDABA CLASS OF '48. Grade Two students of Candaba Central School, post-war batch 1947-1948.On 21 August 1901, the Thomasites—a group of teachers recruited from America—arrived in Manila Bay, Philippines on board the transport U.S.A.T. Thomas with the intent of introducing a new system of public education in the country. Twenty five were fielded to the province of Pampanga, and three teachers made their way to Candaba town.

The Candaba Thomasites not only taught by example and trained local teachers, they were also instrumental in setting up schools. On 6 February 1902, they helped put up the Candaba Central School in the Poblacion at a cost of P1,000. The Candaba Central School was the predecessor of the Candaba Elementary School, which continues to be a primary institution of learning for the children of Candaba.

In 1908, under the municipal presidente Pedro Evangelista, barrio schools were established in Lanang and Bahay Pare. Due to the growing higher education needs of the town, intermediate schools (offering Grade V thru VII) were established in Barrio Salapungan and Barrio Mandasig.

The Candaba Thomasites not only taught by example and trained local teachers, they were also instrumental in setting up schools. On 6 February 1902, they helped put up the Candaba Central School in the Poblacion at a cost of P1,000. The Candaba Central School was the predecessor of the Candaba Elementary School, which continues to be a primary institution of learning for the children of Candaba.

In 1908, under the municipal presidente Pedro Evangelista, barrio schools were established in Lanang and Bahay Pare. Due to the growing higher education needs of the town, intermediate schools (offering Grade V thru VII) were established in Barrio Salapungan and Barrio Mandasig.

Sunday, January 30, 2011

*235. Father to the Lost and the Lonely: Rev. Msgr. BENEDICTO J.E. ARROYO

HE WHO COMES IN THE NAME OF THE LORD. The young Candaba-born Benedicto Arroyo as a high school graduate, age 17 . Future chaplain of the National Bilibid Prison and National Mental Hospital. Ca. 1934.

HE WHO COMES IN THE NAME OF THE LORD. The young Candaba-born Benedicto Arroyo as a high school graduate, age 17 . Future chaplain of the National Bilibid Prison and National Mental Hospital. Ca. 1934.I remember seeing Msgr. Benedicto Arroyo at the Cardinal Santos Memorial Hospital sometime in 2004 when I visited a sick aunt. I was with my Del Rosario-Tinio relatives when we chanced upon him in the elevator. The Tinios were related to him by marriage and an uncle-priest, Msgr. Manuel del Rosario, who was a dear friend of his.

In his 80s, the portly father was still at it, in a hospital, no less, ministering to the infirmed and the sick, a calling that he embraced, and which would become the hallmark of his long career as a Filipino religious.

The good monsignor was born in Candaba on 16 August 1917, the fifth child of Dr. Esteban Sadie Arroyo and Adela G. Evangelista. His father was a University of Sto. Tomas medical graduate and he was, at one time, the presidente municipal of Candaba and a co-founder of the Arayat Sugar Central. The large Arroyo brood would grow to twelve children; aside from Benedicto, his siblings included Eduardo, Juan, William, Elena, Caridad, Socrates, Didimo, Sosimo, Aquiles, Africa and Pomposo.

Just like his brothers and sisters, Benedicto attended his primary grades at the local Candaba Elementary School. Bent on pursuing his religious vocation, he entered the San Carlos Seminary for his secondary education, and, upon completion, enrolled at the San Jose Seminary at age 17. He finsihed his priesthood at the height of the war on 20 March 1943, with the Most Rev. Michael Dougherty D.D. as his ordaining prelate.

His first assignment was as Assistant Parish Priest at Guiguinto, Bulacan (1943-46), and after which he was stationed at Tarlac, Tarlac for a year (1946-47). His next post was at the St. John the Baptist Parish in Pinaglabanan, San Juan (1947-55). The next two years of his religious life were spent ministering to the mentally sick, the physically infirmed and hardened criminals as Chaplain of the National Mental Hospital, National Orthopedic Hospital, and New Bilibid Prison, Muntinlupa.

Fr. Arroyo would prove his mettle during his term as an NBP chaplain. He celebrated Masses, heard inmates’ confessions and celebrated Christmas with his wards. He looked after the spiritual welfare of the inmates, firm in his belief that, like the parable of the prodigal son, they, too, are capable of finding their way back to God. So well-loved and effective was he, that he was promoted to Chief Chaplain and became a Penal Catholic Chaplain Coordinator in 1962. He likewise became a member of the Board of Pardon and Parole and headed the Classification Board of the National Bilibid Prison as its Chairman.

Fr. Arroyo would eventually be assigned to the Parish of San Rafael in Pasay City and become a Vicar Forane of the Vicariate of St. Raphael. Despite his many functions, he found time to become the Spiritual Director of the Maria Coronada movement as well as an esteemed member of the Archdiocesan Pastoral Council.

The monsignor also loved travelling, and his sojourns have taken him all over Europe and the United States where he has many relatives. He observed his Diamond Sacerdotal Jubilee in 2003 and spent his retirement years at Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary. Msgr. Benedicto J.E. Arroyo passed away on 21 September 2010 at the grand age of 93. He is interred at the Manila Memorial Park in Sucat, Parañaque.

Benedictus Qui Venit In Nomine Domini

(Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord)

Sunday, December 19, 2010

*228.Teeth for Tat: KAPAMPANGAN CIRUJANO-DENTISTAS

CLOSE-UP CONFIDENCE. Dr. & Mrs. Tomas Yuson (the former Librada Concepcion) on their wedding day in 1936. Dr. Tom Yuson was the leading Kapampangan dentist in his time, and a co-founder of the Pampanga Dental Association in 1930. Personal Collection.

CLOSE-UP CONFIDENCE. Dr. & Mrs. Tomas Yuson (the former Librada Concepcion) on their wedding day in 1936. Dr. Tom Yuson was the leading Kapampangan dentist in his time, and a co-founder of the Pampanga Dental Association in 1930. Personal Collection.Pampanga is renowned for its eminent medical doctors and surgeons of superb skills. The names of Drs. Gregorio Singian, Basilio Valdez, Mario Alimurung and Conrado Dayrit come to mind. The allied course of Dentistry has also given us notable Kapampangans professionals who have made a name for themselves in this less crowded field of dental science, and their achievements are no less significant.

In the first decades of the 20th century, when colleges and universities started offering medical courses, students were drawn more to Medicine and Pharmacy. Dentistry was not even considered a legal profession during the Spanish times--tooth pullers were employed to take care of problem molars, cuspids and bicuspids.

As public health was given emphasis during the American regime, the course of dentistry was given legitmacy with the opening of the Colegio Dental del Liceo de Manila. It would become the Philippine Dental College, the pioneer school of dentistry in the Philipines. Students started enrolling in the course as more schools like the University of the Philippines opened its doors to students. The state university established its own Department of Dentistry that was appended to its College of Medicine and Surgery. The initial offering attracted eight students. That time, with a population of eight million, there was only one dentist to every 57,971 Filipinos. More educational insititutions would follow suit: National University (1925), Manila College of Dentistry (1929) and University of the East(1948. In 3 to 4 years, these schools would be graduating doctors of dental medicine, many of whome were Kapampangans.

One of the more accomplished is Guagua-born Tomas L. Yuzon, born on 7 March 1906, the son of Juan Yuzon and Simona Layug. He attended local schools in Guagua until he was 16, then moved to Philippine Normal School in Manila. At age 20, he enrolled at the country’s foremost dental school, the Philippine Dental College, and finished his 4-year course in 1930. That same year, he passed the board and began a flourishing career as a Dental Surgeon in San Fernando.

In 1930, together with Dr. Claro Ayuyao of Magalang and Dr. H. Luciano David of Angeles, Yuzon founded the Pampanga Dental Association on 25 October 1930. The constitution, rules and by-laws were patterned after the National Dental Association. The initial members of 30 Pampanga dentists aimed to elevate the standard of their profession and foster mutual cooperation and understanding among themselves. Elected President was Dr. Ayuyao, while Dr. Yuzon was named as Secretary. The P.D.A. was the first provincial organization to hold demonstrations in modern dental practice and was an authorized chapter of the national organization.

As a proponent of modern dental medicine, Dr. Yuzon was one of the first to use X-Ray and Transillumination in diagnosing his patients. He was also an active member of the Philippine Society of Stomatologists of Manila. He received much acclaim for his work, and was a respected figure in both his hometown—where he remained a member of good standing of “Maligaya Club”, as well as in his adopted community of San Fernando. On 19 Sept. 1936, he married Librada M. Concepcion of Mabalacat, daughter of Clotilde Morales and Isabelo Concepcion. They settled in San Fernando and raised three children: Peter, Susing and Lourdes.

Guagua seemed to have produced more dentists than any other Pampanga town in the late 20s and 30s and some graduates from the Philippine Dental College include Drs. Marciano L. David (1925), Emilio Tiongco (1931, worked as assistant to dr. F. Mejia), Domingo B. Calma (who was a town teacher before becoming a dental surgeon), Eladio Simpao (1929), Alfredo Nacu (1929) and Hermenegildo L. Lagman (an early 1919 graduate and also a member of the Veterans of the Revolution!)

The list of of Angeleño dentists is headed by Dr. Lauro S. Gomez who graduated at the top of his class at National University in 1930, Mariano P. Pineda (PDC, 1930, a dry goods businessman and a Bureau of Education clerk before becoming a dentist), Pablo del Rosario and Vicente de Guzman.

In Apalit, Dr. Roman Balagtas placed ads that stated “babie yang consulta carin San Vicente Apalit, balang aldo Miercoles". He also had a clinic in Juan Luna, Tondo. Arayat gave us the well-educated and well-travelled Dr. Emeterio D. Peña, who was schooled at the Zaliti Barrio School, Arayat Institute (1916), Pampanga High School (1916-18), Batangas High School (1918-1919) and at the Philippine Dental College (1920-23). He squeezed in some time to study Spanish at Instituto Cervantino (1921-23). Then he went on to practice at San Fernando, La Union, Tayabas, Mindoro, Nueva Ecija and Tarlac. Also from Arayat were Drs. Agapito Abriol Santos and Alejandro Alcala (both PDC 1931 graduates). The latter was famed for his “painless extractions” at his 1702 Azcarraga clinic which ominously faced Funeraria Paz!

Betis and Bacolor are the hometowns of dentists Exequiel Garcia David (who worked in the Bureau of Lands and as a private secretary to Rep. M. Ocampo) and Santiago S. Angeles, respectively. Candaba prides itself in having Dr. Dominador A. Evangelista as one of its proud sons in the dental profession while Lubao has Gregorio M. Fernandez, a 1928 Philippine Dental College graduate, who went on to national fame as a leading film director, and Daniel S. Fausto, who graduated in 1934..

Macabebe doctors of dental medicines include Policarpio Enriquez , a 1931 dentistry graduate of the Educational Institute of the Philippines, Francisco M. Silva PDC, 1923) who also became a top councilor of the town. Magalang gave us the esteemed Dr. Claro D. Ayuyao who became the 1st president of the Pampanga Dental Association and Dr. Alejandro T. David, a product of Philippine Dental College in 1928, who was also a businessman-mason.

Dentists Dominador L. Mallari (PDC, 1932) and Pedro Guevara (UST, Junior Red Cross Dentist 1923-29) came from Masantol. Guevara even went on to become a councilor-elect of his town. The leading dentist from Minalin, Sabas N Pingol (PDC, 1929) announced that: “manulu ya agpang qng bayung paralan caring saquit ding ipan at guilaguid’. He moved residence to Tondo and kept a clinic at 760 Reyna Regente, Binondo.

In Sta. Rita, Drs. Maximo de Castro (PDC, 1931) and Sergio Cruz (PDC, 1932) had private practices in their town. Finally, well-known Fernandino dentists of the peacetime years include Paulino Y. Gopez (UP, College of Dentistry, 1931) and the specialist Dr. Miguel G. Baluyut, (PDC, 1927) who took a course in Oral Surgery at the Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois. Trailblazers of some sorts were lady dentists Paz R. Naval, a dental surgeon, Consuelo L. Asung who held clinics in San Fernando and Mexico.

Next time you flash those pearly whites and gummy smiles, think of the early pioneering Kapampangan dentists who, with their knowledge, talents and skills, helped elevate the stature of their profession, putting it on equal footing with mainstream medicine.

Labels:

Angeles,

Bacolor,

Betis,

Candaba,

Guagua,

Kapampangan personalities,

life blog,

Macabebe,

Magalang,

Masantol,

Minalin,

Pampanga,

Philippines,

San Fernando,

Sta. Rita

Thursday, October 28, 2010

*223. PAMPANGA'S PARUL: Spectacular Stars of the Season

TWINKLE, TWINKLE CHRISTMAS STAR. A Kapampangan lass from Barrio Talang in Candaba, Pampanga spruces up their family's humble home with a homemade star lantern crafted from papel de japon, cellophane and bamboo sticks, December 1961.

TWINKLE, TWINKLE CHRISTMAS STAR. A Kapampangan lass from Barrio Talang in Candaba, Pampanga spruces up their family's humble home with a homemade star lantern crafted from papel de japon, cellophane and bamboo sticks, December 1961.Pampanga’s star shines the brightest during the holiday season, in both literal and figurative sense, as it brings out its dazzling, colorful paruls (lanterns) to light up the nights leading to Christmas. While the lantern tradition is not unique to the Philippines—Oriental countries like Japan and China are likewise famous for their lighted paper lanterns with their characteristic tassels—it can rightfully claim to be the home of the most spectacular Christmas lanterns in the world, courtesy of Pampanga.

The parols in Pampanga, like all lanterns in the Islands, started with simple, boxy paper lanterns with wooden frameworks held on bamboo poles and borne to light early religious processions, as in the lubenas of the Virgen de La Naval in Bacolor. ‘Parol” was localized from the Spanish ‘farol’ (lantern), which, in turn was derived from “Pharos”, a Grecian island along the Nile renowned for its lighthouse that came to be part of the world’s seven wonders. The lanterns soon acquired the shape of a star and even a tail, to represent the Star of Bethlehem that shone over Christ’s birthplace in Bethlehem.

For many years, the basic construction of the parol remained unchanged—bamboo sticks form the framework for the three-dimensional five pointed star, which is then covered with papel de japon of suitable color. The bamboo frames are lined with strips of foil paper to define the star and one or two tails of are added, also made from paper strips. The star can also be accentuated with foil cut-outs and circumscribed with a papered bamboo hoop. Several variations were spun-off from this basic parul, including lanterns with multiple points and, of late, paruls fashioned from translucent capiz shells, fiberglass, colored vinyl and handmade paper.

SAN FERNANDO PARUL FROM 1964, shows a star-shaped center with santan flower designs in between, circumscribed by 5-petal flowers.

SAN FERNANDO PARUL FROM 1964, shows a star-shaped center with santan flower designs in between, circumscribed by 5-petal flowers. But it took the people of San Fernando to re-invent the ‘parul’ , transforming them into the giant, spectacularly-lit lanterns that we know today. The advent of electricity in the 1930s solved the lighting problems of lanterns, and so artisans focused their attention in enhancing the design and size of the common ‘parul’.

The Davids from barangay Sta. Lucia, are a family of lantern-makers who were crafting ‘paruls’ as early as the 1930s. The patriarch, the late Rodolfo David, is credited with inventing the rotor, which revolutionized the design and lighting mechanisms of paruls, allowing for countless lighting possibilities and color combinations.

To maximize such attractive kaleidoscopic effects, lanterns grew in size, with the first battery-powered giant lanterns devised by David’s son-in-law, Severino, in the early 1940s. By 1958, David had perfected a new lantern design, papered with papel de japon, and now distinctively known as ‘parul sampernandu’. The flat, circular lanterns are designed with individual compartments housing a lightbulbs that light and ‘dance’ using the ingenious rotor technology devised not ny engineers, but by local craftsmen. Rotors are fashioned from barrels, which are rotated manually by a person to light the lanterns—the same principle employed by small music boxes that has rotors with embossed parts that sound off when they come in contact with the steel tines.

CLASSIC PARUL DESIGN, shows a kaleidoscope of colored patterns--curlicues, spirals, arches and mosaic patterns. Ca. 1964.

CLASSIC PARUL DESIGN, shows a kaleidoscope of colored patterns--curlicues, spirals, arches and mosaic patterns. Ca. 1964.In the case of sampernandu lanterns, the electricity is activated with hairpins when they come in contact with the metal rotor. Strategically-placed masking tape on the rotor, on the other hand, cuts off the flow of electricity. This stop-and-go flow of electricity dictates the lighting pattern of the thousands of lightbulbs (some as much as 4,000 bulbs) , achieving the dancing illusion that becomes more apparent when the lighting is synched with live band music.

Today, the paruls of Pampanga, led by the sampernandu of the capital city, continue to shine brightly with the annual Ligligan Parul (Giant Lantern Festival and Contest) that has helped popularized and revitalized interest in this once-vanishing art. Leading lantern makers like Erning David Quiwa, Eric Quiwa, Roland Quiambao and Arnel Flores are at the forefront of this mision to keep the parul tradition alive.

The Kapampangan paruls have also awed audience worldwide—from Hollywood U.S.A. (where a float decorated with sampernandu lanterns won first prize in a folk festival), Thailand, Taiwan, to Austria and Spain. Always a community affair, the making of Christmas lanterns also helps to keep the flame of bayanihan spirit burning, encouraging generosity, charity, goodwill and peaceful co-existence, which are, in fact, the same messages that Christmas brings.

MASAYANG PASKU AT MASAPLALANG BAYUNG BANWA KEKO NGAN!

Sunday, May 2, 2010

*196. EDDIE DEL MAR, Kapampangan 'Rizal' of the Silver Screen

MI ULTIMO RIZAL. Eduardo "Eddie" del Mar gave such a stirring and unforgettable performance as the national hero in the movie "Ang Buhay at Pagibig ni Dr. Jose Rizal", that his name has become permanently linked with that prized role. This is a small, giveaway photocard of the Kapampangan actor, ca. 1950s.

MI ULTIMO RIZAL. Eduardo "Eddie" del Mar gave such a stirring and unforgettable performance as the national hero in the movie "Ang Buhay at Pagibig ni Dr. Jose Rizal", that his name has become permanently linked with that prized role. This is a small, giveaway photocard of the Kapampangan actor, ca. 1950s. The life of our national hero, Dr. Jose P. Rizal has been the subject of many Philippine movies through the years. The first Rizal biopic was entitled “La Vida de Jose Rizal”, filmed by theater-owner Harry Gross in the first decade of the 1900s. Honorio Lopez, a writer-actor, got the plum role of Rizal. Gross would later make the first film adaptations of the hero’s novels, “Noli Me Tangere” (1915) and “El Filibusterismo” (1916).

Many actors have essayed the role of Rizal since— Joel Torre, Albert Martinez and Cesar Montano are but two contemporary actors who have won acclaim for portraying him. But the one movie star most famous and identified with the prized role of Rizal is none other than the Kapampangan film great of the 50s and 60s, Eduardo ‘Eddie’ die del Mar.

Eduardo Magat was born on 13 October 1923 in Candaba , Pampanga, the son of Albino Magat and Benigna Sangalang. After finishing his Associate in Arts course, he enrolled at UST to study medicine, but the war intervened. He was set to join the ROTC contingent bound for Bataan but became a guerilla fighter intead, almost losing his life for his underground activities.

After the War, he resumed his medical studies--until a classmate of his, Lucas usero, a relative of the Veras of Sampaguita Pictures, brought him along to a party at the Vera residence. Mrs. Dolores H. de Vera offered to screen-test him under Gerry de Leon's direction. He passed the test and became a featured player in "Kapilya sa May Daang Bakal" (The Chapel by the Railroad) starring Oscar Moreno and Tita Duran. Directed by Tor Villano, he was intridyced as 'Eduardo del Mar'. He was next cast in “La Paloma” (1947), directed by Tor Villano, with Paraluman, Fred Montilla and Lilian Leonardo as lead stars. He was unbilled in that movie, but he made quite an impression that his star was soon on the rise.

In the next few years. Eddie was kept busy doing movies not just for Sampaguita but also for the Nolasco Brothers, Liwayway and Lebran Pictures. He made his mark in such movies as "Lumang Simbahan" (1949), "Kilabot sa Makiking", "Huramentado" (1950), and Lebran’s first anniversary movie presentation, “The Spell”, which was in English. It was at Premiere Productions that he renewed acquaintance with director Gerardo de Leon with whom he made his most memorable film "Sisa" where he took on the role of Crisostomo Ibarra. Again, his performance generated much buzz and an acting nomination, overshadowed only by Anita Linda's, who was named Best Actress that year. The 1951 film itself won the top "Maria Clara Award". Thus began his association with "Rizaliana movies".

In 1952, he played the title role of “Trubador”, a Filipino folk hero who was a rig driver by day and a protector of the oppressed by night. He did “Bandilang Pula“ in 1955 for which he would receive his first Film Academy of Arts and Sciences (FAMAS) Best Actor nomination. Suddenly, Eduardo delMar found himself among the big leagues of Philippine moviedom.

It was his 1956 film, “Ang Buhay at Pag-ibig ni Dr. Jose Rizal” that would change his showbiz career forever. Produced by Balatbat and Bagumbayan Production, this movie that dramatized the romances of our national hero. He was joined in this movie by Edna Luna, Corazon Rivas and Aida Serna, under the able direction of Ramon Estela. Eduardo, in the title role, was so effective and memorable in his portrayal of the national hero that, in the minds of moviegoers, he and Rizal were one. This was not lost on the FAMAS jury who gave him the Best Actor Award for 1956, a highlight of his career. This role would influence his movie project choices for the rest of his life, mostly with patriotic and heroic themes.

Another unforgettable opus would come 5 years later in the movie adaptation of “Noli Me Tangere” of Bayanihan-Arriva Films. The film was made to commemorate the birth centenary of Rizal in 1961. “Noli” was megged by the brilliant Gerardo de Leon, and in this Rizal masterpiece, Eddie del Mar copped the role of Crisostomo Ibarra, with Miss Philippines Edita Vital as Maria Clara and Leopoldo Salcedo as Elias. Eddie actually conceptualized this ambitious project, and when it was premiered at the Galaxy Theater on Avenida, it proved to be a blockbuster hit, grossing over P100,000 in its first week of showing alone.

In the 10th FAMAS derby that year, he found stiff competition from his co-star Leopoldo Salcedo, who edged him out for the Best Actor award. “Noli Me Tangere” would win the top award for the evening as the “Best Film” of the year, with its director, Gerardo de Leon, earning another Best Director trophy. But what Eddie cherished more was his being named as a "Knight of Rizal", during the 99th birthday of Jose Rizal, a distinction he received in Calamba, Laguna.

Eddie continued his winning streak by appearing in “Sino ang Matapang” in 1962, for which he was nominated again for Best Actor. Gerry de Leon’s “El Filbusterismo” also was released the same year with Eddie conspicuously absent from the star line-up. As if to showcase his versatility at portraying roles of opposing character and temperament, he appeared as the revolutionary hero, Andres Bonifacio, in the 1964 epic, “Andres Bonifacio (Ang Supremo)”.

Eddie del Mar disappeared from the movie scene in the 1970s, but resurfaced as part of the cast of the popular hit, “Tinik sa Dibdib” in 1986. A son, Louie Magat, briefly dabbled in showbiz, assuming the screen name, Eddie del Mar Jr. to honor his father. Eddie del Mar died on 8 November 1986, but his memory lives on in his films, most especially his Jose Rizal movie classic, that not only immortalized the talent of this Kapampangan screen luminary, but also brought back to our consciousness, the life and loves of our national hero.

Sunday, October 25, 2009

*167. PILOTS OF THE AIRWAVES