|

| Picked Me Pink: ATSARA, pickled vegetables, presented artfully. |

The Philippines share many food preserving traditions

with its Asian neighbors, the most popular being pickling fruits and

vegetables. Our term for such preserved condiment is “atsara / achara”, from the Indian

“achaar”, a generic term for anything pickled. India’s stamp on our regional cuisine

is evident as well in Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and Brunei, where the

condiment is called “acar” or “atjar”.

Just about any fruit or vegetable can be pickled, depending on the country’s produce. Indian prefer green mangoes, lemons, carrot, chickpeas. Pickling, like its allied processes like fermenting, preserving by sugar, and drying is a way of extending the shelf life of food, and ensures availability of out-of-season fruits, vegetables and other produce.

|

| ACHARA Atbp, from "Filipino Heritage:The Making of a Nation" |

Papaya is the most common choice in Southeast Asian

countries, including the Philippines. The pickling medium also varies—Japanese

and Korean kitchens use salt, rice bran, miso (fermented bean paste), and mustard,

while Indian cooks use mustard or sesame oil.

Our local achara, made from green papaya laced with carrots, pepper, onion and optional raisins, is sweet and tangy. Its table uses also vary—as a side dish, dipping sauce, flavor breaker from the sameness of food, or relish to accompany longganisas and fish. I know at least one person who eats atsara as salad!

|

| MARMALADAS y CONSERVAS: Orange, Pineapple, Kundol, Papaya |

But it is in the manner of presentation that the Philippine achara is truly distinctive.While the pickling process is relatively simple--- upon boiling the fruit ‘n vegetable mix, the pickling syrup takes over—and in a week’s time or longer, the atsara is ready to eat. It is the preliminary preparation of ingredients, however, where the creativity of local cooks found full expression. Grating the papaya is easy enough, but artistic cutting of the other achara ingredients requires a higher level of skill and attention.

Before placing in bottles for pickling, the vegetable and fruit pieces were delicately cut and carved with intricate designs—carrots were fancifully shaped into flowers, cucumbers became foliage or rosettes, and melons scooped into balls.

|

| FRUITY FRETWORK, Sunday Time Magazine, 1966 |

This vegetable and fruit carving tradition harkens back

to the ancient ages in Japan, where it began and known as “mukimono”, then spread to the Malay region where the

practice was adapted in local kitchens. The art thrived in some countries like Cambodia

and Thailand especially, but not in the Philippines where, even before World

War II, papaya carving was already a dying art.

Food technologist (and later, war heroine) Maria Orosa, of The Bureau of Plant Industry, sought to revive the art by gathering trainees to learn the skill. Most of the talents came from Bulacan. One, Mrs. Luisa A. Arguelles of Meycauayan was a master carver of not just papayas, but kundol, candied orange and camote. She carved silhouettes of people’s profiles, various font styles, and figurals from peels and flat fruit pieces. Another, Mrs. Presentacion de Leon used locally-invented carving tools to make elaborate fruit and vegetable pieces that were shaped like balls, curls and petals.

|

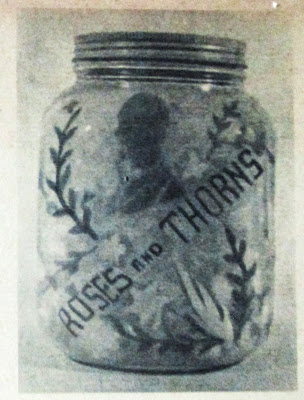

| ROSES AND THORNS, Vegetable Carving, STM 1966 |

Once the boiled in the pickling solution, the mixed fruit-vegetable

achara is placed in wide-mouthed jars and the carved vegetable pieces are

arranged and coaxed into positions to form

pleasant scenes and words (e.g. “recuerdo”, “ala-ala”, “amistad”). The

bottles or jars are then sealed and let to stand on display on the aparador

platera for all to see. The merits of these bottled achara lie not only in

the decorative folk artistry but also in the rich flavor of its varied contents.

Aside from the papaya-based achara, green mangos, kamias, radishes, and santols were also pickled in brine water. Filipino homemakers—from big cities to rural barrios—learned the art of pickling and preserving early—informally or home economics classes. Proof of their kitchen wizardry was when a group of Filipinos, mostly from Pampanga, won merit awards at culinary contest held at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

|

| FRUIT AND VEGETABLE CARVING TOOLS, Sunday Times Magazine, 1966 |

Among those recognized was Atanacio Rivera de Morales

(buri palm preserves ); Isabel Mercado (preserved limoncito); Irene Canlas

(preserved melon); Maria Guadalupe Castro (santol jelly); Rafaela Ramos Angeles

(santol preserves) and Justa de Castro (kamias fruit preserve).

Imported pickled cucumbers in bottles were available in the Philippines in the 1930s under the Del Monte (Achara de Pepinillos) and Achara Libby’s brand. Local attempts to commercialize production of similar products began when American Mrs. Gertrude Stewart arrived in the Philippines in 1928. Living here, she was disappointed to find recipes in magazines calling for ingredients not found in the country so she created new recipes integrating local produce.

|

| From vegetables and fruits--to blooms, petals, and flowers!! |

In 1959, Mrs. Stewart was contracted by Estraco Inc, a distributing company, to supply pickles, fruit preserves and marmalade products for their new food division. Thus Mrs. Gertrude Stewart Homestyle Foods was born. Her greatest contribution to the food industry is the utilization of native Philippine fruits like the duhat, bignay and sayote that she used to create mock maraschino cherries.

|

| CUT ABOVE THE REST. An expert fruit and vegetable carver |

Today, the bottled achara has become a familiar offering

in pasalubong stores, food stalls and even big groceries and supermarkets,

supplied by small to medium sized home industries. Packaged in bottles labeled with

catchy brand names, the commercial atsara may still hold the same taste appeal,

but for sheer visual attraction, nothing can match the presentation of atsaras

of yesteryears.

Though some might dismiss this pleasing bottled arrangement as purely culinary, the art of fruit and vegetable carving/cutting is part of our cultural heritage, a charming form of folk art where food becomes the art itself.

For to fashion a santol into a multi-petalled dahlia flower, to create stars out of carrots, green papaya into curlicued leaves, mangos into palm fronds, to carve sentiments of love and names of beloved on a pomelo, constitutes a skill worthy of an artistic genius.

SOURCES:

All About Achaar, the

Indian Pickle: Recipe and Tips, Written by MasterClass

The Folk Art Issue, The

Sunday Times Magazine, May 1963

The Food Issue, The Sunday

Times Magazine, 1966

“Let’s Preserve our

Preserves”, The Sunday Time Magazine, 12 March 1961 issue, p. 32

“Conservas”, The Tribune, 25

Nov. 1933, Rotogravure Section, p. 3.

Homefront section, The

Tribune, 10 Dec. 1943, p. 27